Heritage is a verb

The older I get, the more I understand the pull of stories.

Maybe it’s because I have children now. Small people who already ask questions about where we come from, who came before us, why we do things the way we do.

And suddenly, I want to know too. Not just the factual structure of our family tree, but the stories that live beneath the branches.

The rituals, the recipes, the small, unremarkable habits that quietly hold us together.

I want to know my past.

The past of the place where I live.

The stories of my friends’ parents, the names of the fields that no longer exist, the reasons behind our local customs that no one can quite explain but everyone still follows.

Because knowing where we come from helps guide where we, and our children, might go.

In a Sardinian village

In the Sardinian village of Orgosolo, neighbours and artists have spent decades repainting the murals that cover their walls. Scenes of farmers, protests, and daily life. Some are retouched, others replaced, new ones added. The paintings change, as villages do.

No museum guards them, but the people keep them. With brushes, memory, and care.

Orgosolo (photos via mooistedorpjes.nl)

That is heritage.

Not the kind locked in glass, but the kind that breathes.

The kind that changes and still remembers where it came from.

What we keep

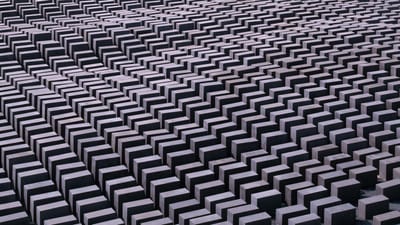

We often think of heritage as grand: cathedrals, monuments, artefacts behind alarms.

But most of what binds a community isn’t carved in stone.

It’s kept in gestures, recipes, and stories that travel quietly from hand to hand.

The way a village still rings its bell for the same feast day.

The Saturday market that feels exactly like the one your grandmother described.

The corner shop that still writes prices in chalk.

The local words that never made it into the dictionary but live on in conversation.

In Bergen op Zoom, the city I come from, it’s the way families prepare for Vastenavend: the carnival that begins not with the parade, but at home. Costumes are sewn from old fabrics at kitchen tables, pots of soup simmer while music from the local radio fills the house, and every scarf, button, and colour carries meaning. Dressing up is not disguise but recognition: a way of saying we belong here. Neighbours drop by to share a drink, children learn the songs and the dialect, and for a few days the town becomes one big household.

These small continuities are the threads of belonging.

They make a place feel like itself.

They make people feel like they belong to it.

Heritage as participation

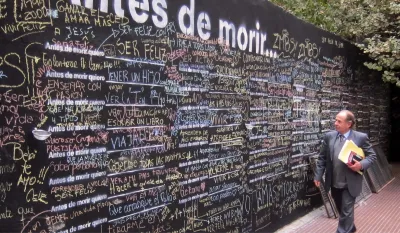

In 2005, in the Portuguese city of Faro, European nations signed a convention that redefined heritage as something shared, not owned. It said that everyone has the right to participate in heritage, to benefit from it, and to contribute to its enrichment.

It’s a conversation. Between people, past and present. And like every good conversation, it only lives if people keep talking.

It sounds bureaucratic, but it was quietly revolutionary. Because it recognised what communities already knew: heritage isn’t a collection of things.

It’s a conversation. Between people, past and present. And like every good conversation, it only lives if people keep talking.

Keeping is an act of care

Keeping isn’t passive.

It’s work.

Someone mends the banner before the next parade.

Someone records a song before it’s forgotten.

Someone plants an old variety of seed in a modern garden.

Every small act of care is a refusal to let the past disappear completely. Every act of keeping says: this still matters.

Heritage, then, isn’t about ownership. It’s about attention. It’s not about freezing time, but understanding where things come from so change doesn’t erase meaning.

The melody gains a new verse, but the rhythm stays.

The building gets rebuilt, but the same stories are told within its walls.

The festival evolves, yet everyone still gathers on the same day.

Change isn’t the opposite of heritage.

Forgetting is.

But sometimes keeping is complicated. Some traditions carry shadows. Parts of the past that no longer fit who we are. They can hold both beauty and harm in the same breath.

I think about the Dutch Sinterklaas, a festival I grew up with: its warmth, the excitement, the smell of speculaas and mandarins, the songs that mark the start of winter. But also the unease that has grown around it, the arguments, the recognition that joy for some came at the cost of others. What do we do with that?

To care for a tradition is not to freeze it in time, but to ask it to grow with us. To keep the good (the generosity, the wonder) and let go of what wounds. Keeping, then, becomes an act of listening forward: holding what still connects us, while allowing space for what must change.

Because heritage that refuses to evolve stops being care: it becomes nostalgia. And heritage that listens becomes possibility.

The power of small communities

The world celebrates scale. Bigger, faster, louder.

But heritage thrives in the small.

In the rooms where everyone still knows each other’s stories.

In places where memory is local, not curated.

In Ermelo (the Netherlands) villagers still gather for the Oogstfeest. The harvest day when old tools are lifted from barns, horses pull ploughs once more, and bread is baked in wood-fired ovens. Not for tourists, but to remember the rhythm of the fields, the sound of work that shaped the land.

It is the Belgian village with its local radio filled with local dialect, voices that sound like the soil they come from.

It is the neighbourhood in Marseille where children learn the calligraphy and recipes of their grandparents’ villages, keeping the lines of belonging alive through taste and touch.

It is Día de los Muertos in Mexican villages, where families build altars to welcome their dead home for one night. A celebration of love that turns grief into colour.

It is Sami singer Sofia Jannok, her voice carrying joik chants across modern beats. Global in reach, intimate in origin.

These are not heritage projects.

They are simply ways of being.

Together, they form the living memory of Europe.

Fragile, adaptable, human.

Why it matters

Because when we lose the habit of keeping, we lose more than memory.

We lose connection.

We forget how to belong.

Every community needs places, words, and rituals that remind it who it is.

Not to stay the same, but to move forward with continuity.

Heritage is that continuity made visible.

It is the muscle memory of a people.

To keep something is to care for the thread that ties yesterday to today, so that tomorrow still knows where it came from.

So: heritage is a verb

It’s not what we inherit; it’s what we practice.

It’s the doing, not the having.

And it lives best when it’s small:

in the stories we tell, the things we mend,

the places we tend,

the names we still use for the corners of our world.

So notice what survives because someone cared.

Listen for what endures because it still matters.

That is heritage.

That is community.

That is the quiet art of keeping things alive.