Shared Wonder: Designing public spaces for connection

We live in an age of perfect personalization. Our feeds, our headphones, our preferences all tune neatly to “just me.” Yet the more individualised our experiences become, the fewer we truly share.

Ask people about the moments that shaped them and they rarely mention something done alone. They talk about the night a whole crowd held its breath together, the installation where strangers played without speaking, the ritual where they briefly saw themselves reflected in others.

Public spaces are meant to be shared, but most of the time we move through them as strangers in parallel. Headphones on. Eyes down. Then something in a square or street disrupts the pattern: a playful installation, a curious prompt, a small moment of surprise. People look up, slow down, and sense each other again.

These moments of shared wonder are not decoration. They are social infrastructure. They soften behaviour, spark trust, and turn anonymous places into environments where people feel part of a larger “we.” And the essential idea is this: shared wonder can be designed. Through co-creation, synchrony, simple rituals, and gentle invitations, public spaces can make connection the natural response rather than the rare one.

Below are examples of how this works in practice and what they teach us about designing places where people do not simply pass one another, but quietly and playfully connect.

21 Balançoires (21 Swings)

📍 Montréal, Canada

In Montréal’s Quartier des Spectacles, a long row of glowing swings transforms an ordinary stretch of pavement into a musical playground. Each swing plays a tone when it moves, but the real magic appears only when people swing together. Melodies form, rhythms sync, and strangers wordlessly coordinate. Children pull adults into the rhythm, adults rediscover play, and a public square briefly becomes a small collective orchestra.

What it teaches us:

Connection grows when participation is simple, playful, and co-dependent. One person can make a sound; only a group can make music.

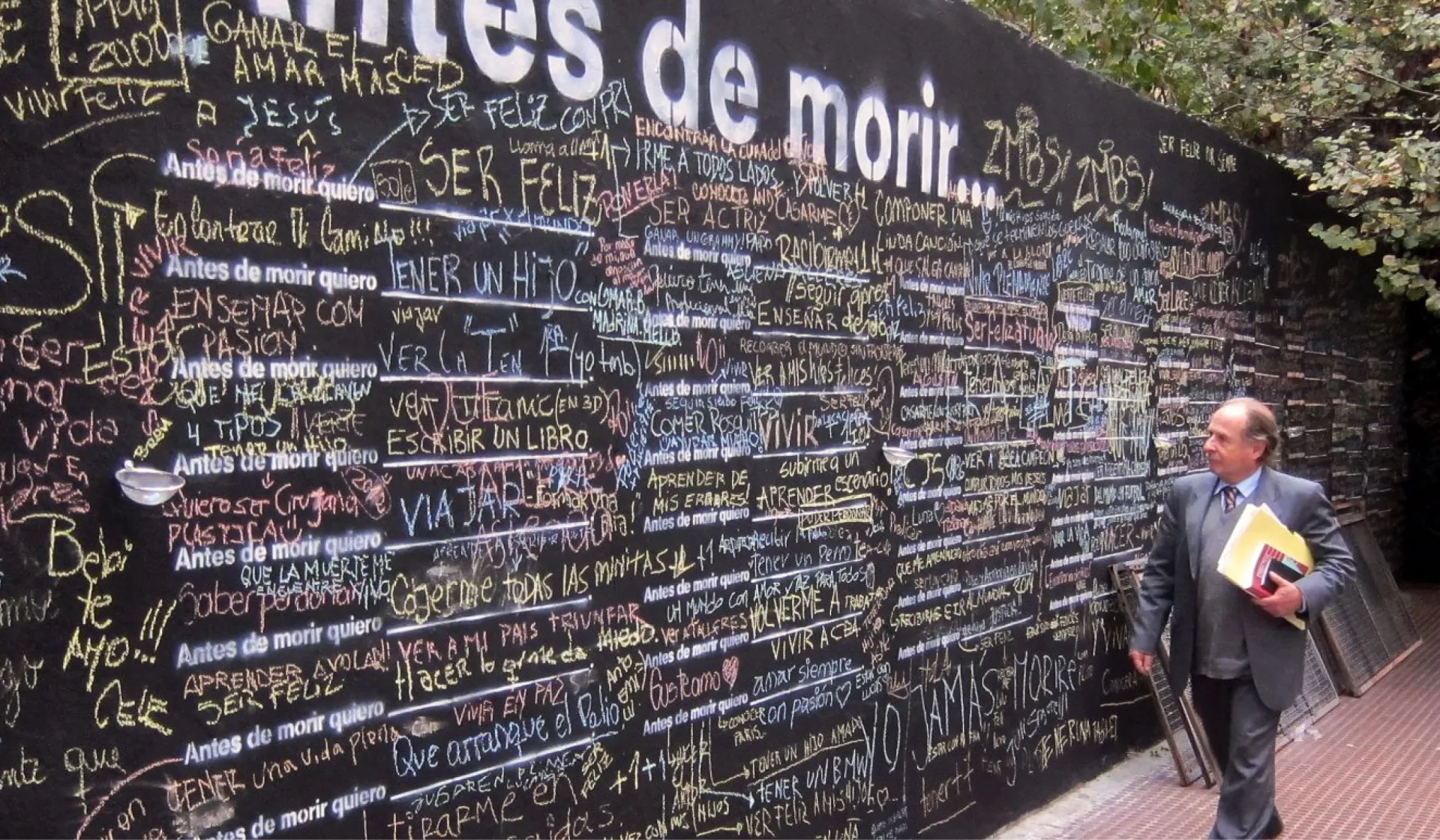

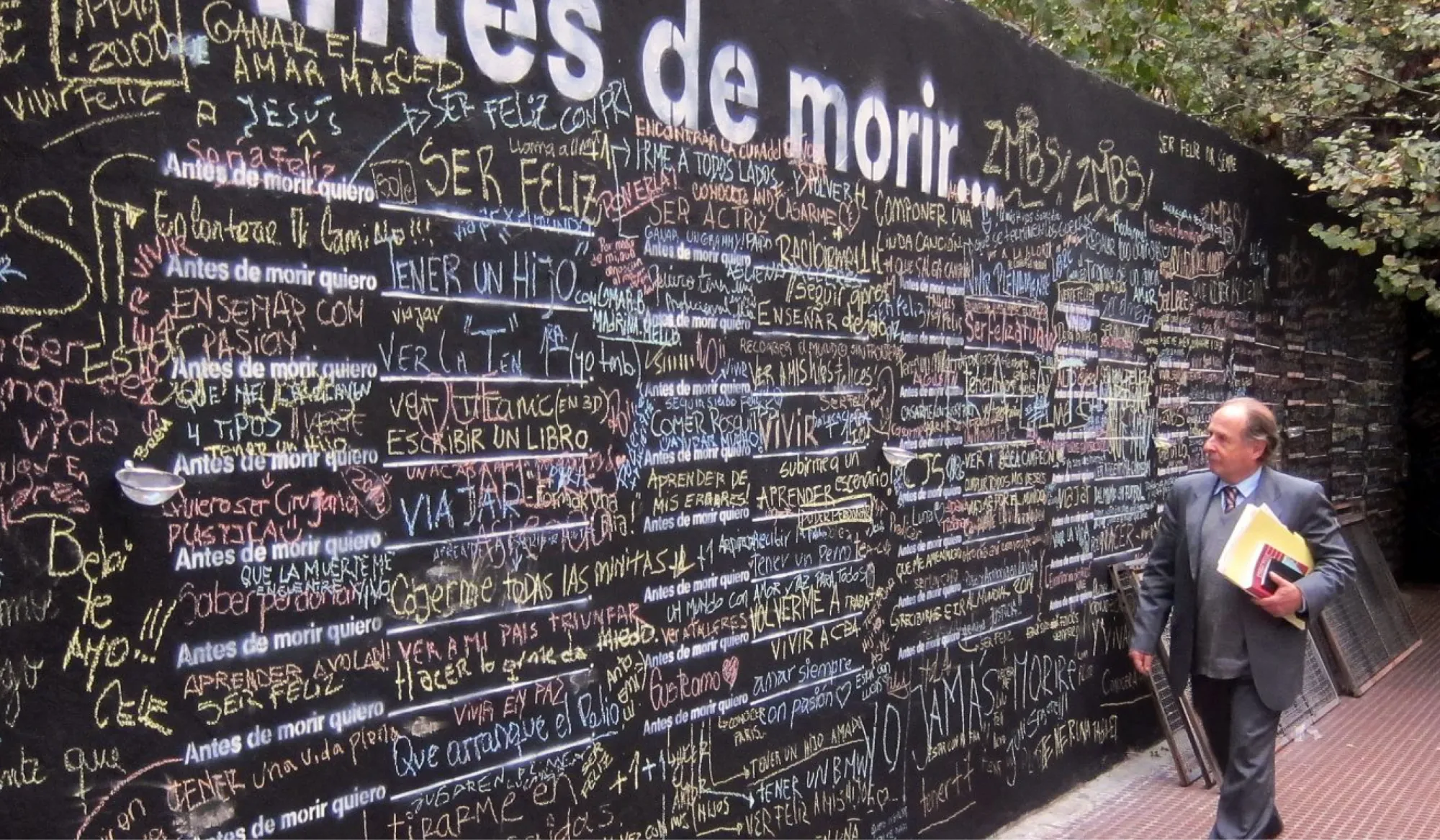

Before I Die Wall

📍 New Orleans, USA

The first wall appeared in New Orleans after artist Candy Chang lost someone she loved. She painted a chalkboard on an abandoned house and wrote: Before I die I want to… Then she left chalk for anyone who wanted to finish the sentence.

By the next morning the wall was full. Some lines were playful. Some were heartbreaking. Some were so raw they stopped people mid-walk. The wall didn’t ask for performance. It didn’t ask for identity. It asked for honesty. And people offered it freely.

What makes the installation powerful is not the quantity of responses but the emotional cross-section: the reminder that behind every window and passing face live private hopes and fears far larger than what we ever see in public.

What it teaches us:

Public space can hold vulnerability. When people are invited to be honest in a non-intrusive way, a neighbourhood’s inner life becomes visible to itself.

A Mile in My Shoes

📍London, UK

The Empathy Museum’s travelling installation often sits quietly on riverfronts or in cultural districts. From the outside it looks like a simple shipping container. Inside is a “shoe shop” lined with shelves, each pair belonging to a real person. You borrow someone’s shoes, put on headphones, and walk.

The stories vary: a grieving parent, a refugee, a sex worker, a beekeeper, a surgeon who has seen too much. As you walk, their voice fills your ears. Sometimes they whisper, sometimes they laugh, sometimes they pause so long you feel the weight of the silence. The effect is intimate in a way public storytelling rarely is. You become aware of your own body inside someone else’s journey. Their steps become your steps. Their memories shape your posture. It is not metaphor. You are literally walking inside another life.

What it teaches us

Embodied storytelling turns empathy into a physical experience. People connect more deeply when they don’t just hear a story but inhabit it.

The Pool

📍 Denver, USA

Jen Lewin’s interactive light installation has appeared in cities from Denver to Sydney to Seoul. Dozens of circular pads lie on the ground, glowing softly. Step on one and it lights up. Move together and waves of colour spread, collide, and ripple outward. Strangers start coordinating their steps, creating living patterns of light with nothing but movement.

What it teaches us

Shared wonder grows when the environment responds to collective action. Collaboration becomes instinctive when it is visually rewarded.

The Human Library

📍Copenhagen, Denmark

The Human Library began in Copenhagen as a simple but radical idea: instead of borrowing a book, you borrow a person. You sit with them for 20 minutes and listen to the story of their life. Not a polished speech. Not a performance. Just a conversation you would never normally have.

Your “book” might be someone who has lived through addiction, or a man who has been in prison, or a woman wearing a hijab who is tired of being asked the same three questions. The setting is gentle and structured, which makes the emotional risk feel safe. And something happens in that small pocket of time: the stereotypes you carried in with you soften. The person in front of you becomes complicated, funny, fragile, fierce, human. And you realise they are not a category. They are a life.

What it teaches us

When public space legitimizes open, patient conversation, strangers discover each other beyond assumptions. Curiosity becomes a bridge instead of a barrier.

Principles & practical tips

These installations succeed not because they are high-tech or spectacular, but because they follow a few quiet, powerful principles. If you want to design for connection, start here:

1. Make participation instantly understandable

People should know what to do without instructions: sit, step, write, walk, listen. Simplicity removes the fear of “doing it wrong.”

2. Reward collective action over individual action

Design outcomes that become richer when more people join: harmonies, ripples of light, layered stories. Connection becomes the obvious choice.

3. Create safe spaces for curiosity

Use gentle structure (clear boundaries, soft materials, intuitive layouts) so people feel comfortable exploring or being vulnerable.

4. Build moments of micro-synchrony

Humans bond when they move or react together. Look for opportunities to sync steps, rhythms, gestures, or breaths.

5. Remove all social pressure

No scoring. No spotlight. No performance. People connect more freely when they don’t feel observed or judged.

6. Let strangers contribute without speaking

Not everyone wants conversation. Provide ways to co-create quietly: write a thought, trigger a light, add a note, just be there and listen, shape a moment.

7. Allow for surprise

Design something slightly magical: a light that responds, a story that walks with you, a sound that appears only through collaboration. Wonder is a spark; connection is what follows.

Why shared wonder matters now

Cities are often described in terms of infrastructure, transport, housing, economics. But the emotional architecture of a city, the way people feel in it, with each other, is just as important.

Shared wonder is one of the simplest tools we have to repair the quiet frictions of modern life: social distance, loneliness, hyper-individualisation. It reminds people that strangers are not threats, that public space is not just a corridor, and that connection can begin with something as small as a swing, a sentence, a pair of shoes, a circle of light, a conversation.

Design won’t solve everything, but it can create the conditions for us to meet each other again.

And sometimes that is enough.