The Different Types of Stability

There are many reasons that humans, us, are attracted to stability. And these reasons are multilayered and interconnected with each other. Since I am a sucker for structure I did try to bring them back to three main reasons and all of them are interconnected.

#1 — The safety of the group

Evolutionary psychology sheds light on our innate inclination to prioritize safety and survival, a trait deeply ingrained in our evolutionary history. Early humans learned that staying within the safety of the group significantly enhanced their chances of survival. And we are not the only ones; throughout the animal kingdom, certain animals have decided that groups might be the best bet. Take, for example, the majestic African buffalo. These massive creatures form tight-knit herds not just for socializing but also for protection against predators like lions and hyenas.

Even in modern times, the concept of safety within a community remains deeply ingrained in our psyche. Belonging to a group provides comfort, support, and validation, reinforcing the importance of stability in our lives.

But in order to fit into a group, leading to social acceptance and validation, we must conform to the standards of that group. This can be the village you live in, the sports club you join, the group of friends you are part of. Each group has its own rules, traditions, and ways of doing things. And to make it fit you must follow the rules and, most of the time, not challenge them. The identity often comes from things that have been set in stone for a long time, so curiosity and exploring beyond the boundaries is not encouraged. History is full of examples that prove this point; take for example the role of women as caregivers and homemakers, stifling their curiosity and ambitions in other domains.

Overall people want to fit in and be part of a group. There is a strong fear of rejection built into humans that keeps us from going in the other direction. There are literally neural pathways associated with physical pain, serving as powerful motivators for conformity. On the other hand we have dopamine in our bodies. This hormone, associated with pleasurable sensations, reinforces behaviors that lead to rewards. Conforming to social norms and being accepted by a group can activate the brain's reward centers, creating a positive feedback loop. (Later on we will learn that dopamine is equally important for curiosity).

Within the group, people find a place. They find stability and give us a sense of identity (we belong somewhere). This principle centers on the desire to preserve one's identity and self-image. People are often resistant to changes that challenge their core beliefs, values, or self-concept. The preservation of identity can contribute to conformity with established patterns that align with one's self-perception. This sometimes causes the individual to be less curious, because of the pressure of the group and the identity connected to that.

Note: Cultural norms and expectations can play a significant role. In some cultures, there might be a strong emphasis on tradition, stability, and conformity. This can influence individuals to prioritize stability in various aspects of their lives, such as career, relationships, and lifestyle choices. There are also cultures that embrace curiosity and exploration. Think of the National Geographic Society.

#2 — The ease of least resistance

Why expend unnecessary energy when there's a more efficient way? It's a fundamental aspect of human nature to seek paths of least resistance, favouring familiarity and routine for their psychological and emotional appeal.

Consider a typical Sunday morning: Despite your initial determination to seize the day, to do sports, visit that new exposition and start baking bread… you find yourself yielding to the allure of your cozy couch. With a sigh, you trade your running shoes for the soft embrace of pajamas and reach for your phone instead of a water bottle. As you sink into the plush cushions of your couch, the intention of a morning jog fades into the background, replaced by the mindless scroll of social feeds and the comfort of familiar distractions. After this a regular day follows, without a new exposition and with that well known easy Pasta Pesto on your plate.

Why? Because our brains are wired for cognitive efficiency. Familiar tasks and routines require less cognitive effort, making them mentally efficient and reinforcing the allure of stability. It's akin to slipping into the comforting embrace of your favourite hoodie rather than exploring new fashion trends. This predisposition for cognitive ease can pose significant challenges, such as solving traffic congestion. Despite the brilliance of numerous solutions proposed by experts, the gravitational pull of routine proves hard to resist.

Our brains excel at processing simple and familiar information, allowing us to slip into a low-energy mode. Think of driving your usual route: there are moments when you arrive home without even recalling parts of the journey, as if on autopilot.

When presented with choices, people often gravitate towards familiar options that require minimal mental effort, even if alternative choices could yield superior outcomes. It's akin to choosing your go-to pizza joint over venturing to a new restaurant—less risky, but potentially depriving yourself of culinary delights.

#3 — The fear of the unknown

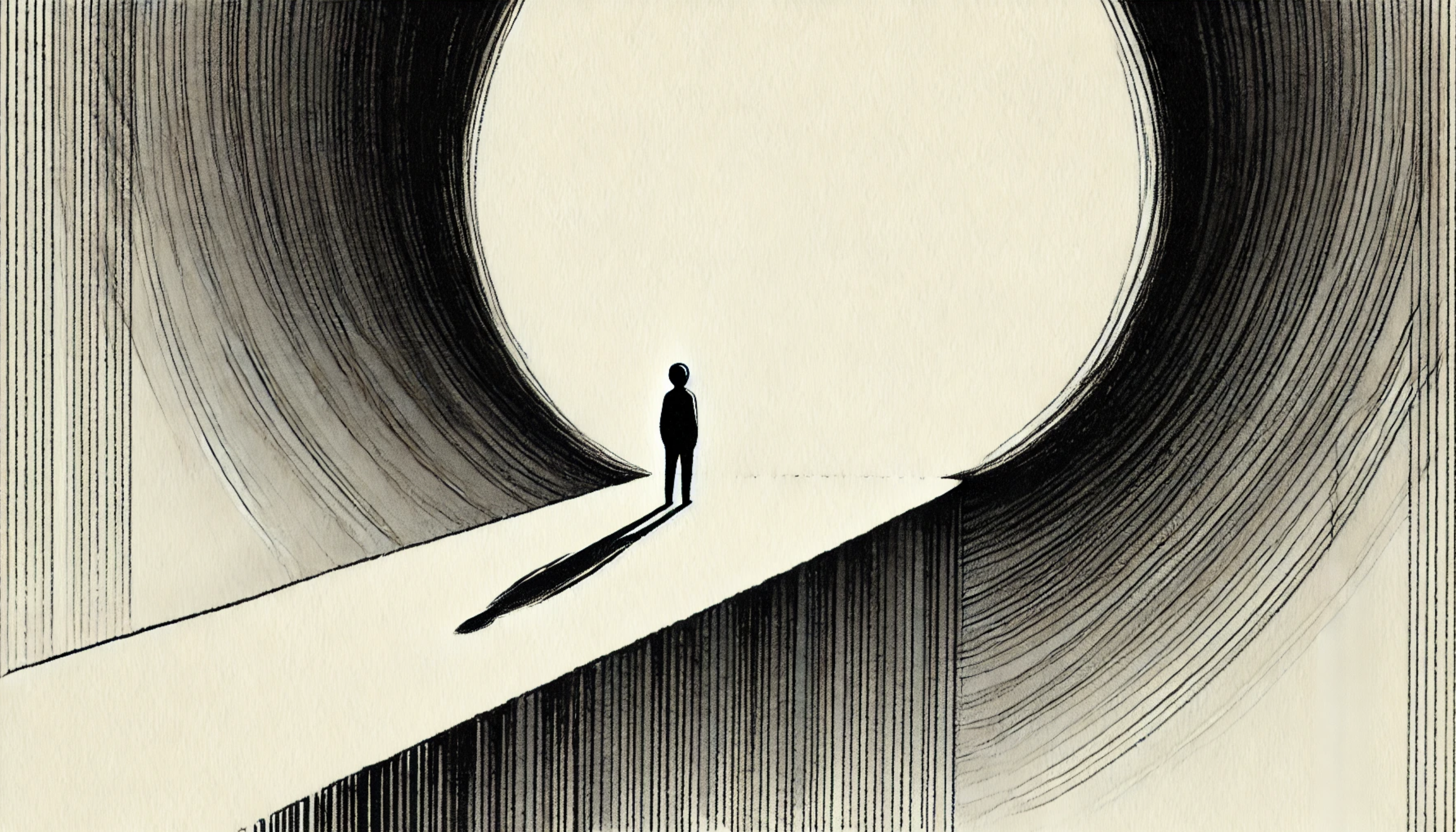

When was the last time you really wanted to do something new and exciting, but decided to not do it because you felt like you could fail? Or that it probably wouldn’t work out anyway?

The fear of the unknown is deeply ingrained in human psychology, influencing our decisions, actions, and overall approach to life's complexities. This fear, rooted in uncertainty and unpredictability, often triggers anxiety and reluctance to venture beyond the familiar. Whether it's the apprehension of embarking on a month-long trip or the nervousness of presenting in front of a crowd, the fear of the unknown can manifest on both personal and societal levels.

Throughout history, we've witnessed the impact of this fear on societal progress. During the civil rights movements of the 1960s, resistance to equality and integration stemmed from fears of disrupting established racial norms. However, as society gradually embraced change, the fear of the unknown began to dissipate, paving the way for significant progress.

In our personal lives, we often cling to the safety net of familiarity and routine, finding comfort in the known and predictable. This tendency is exemplified by the so-called 'endowment effect,' where individuals assign higher value to things simply because they own or are accustomed to them. This reluctance to let go of the familiar can be seen in the initial skepticism surrounding the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs). Uncertainties about charging infrastructure and battery capabilities fueled apprehension. However, as familiarity with EVs grew and technology advanced, the adoption rate surged, showcasing the power of familiarity to overcome fear.

Yet, amidst our innate desire for stability, we often overlook the value of curiosity and the potential for growth that lies beyond our comfort zones. In our modern society, failure is often perceived as unacceptable, leading to a reluctance to take risks or embrace uncertainty. The pressure of "What if we make the wrong choice?" looms large, stifling our curiosity and inhibiting our willingness to explore new possibilities.

Concluding thoughts

Stability offers us comfort, identity, and a sense of belonging, but at what cost? While it protects us from uncertainty, it can also limit our curiosity, growth, and willingness to take risks. Is our pursuit of stability keeping us from embracing change and new experiences? How often do we prioritize familiarity over the unknown, even when the unknown could bring something better? And most importantly, how can we strike a balance between the security of stability and the excitement of exploration? Perhaps the key lies not in rejecting stability altogether but in learning when to lean into it… and when to challenge it.