The Human-Scale Principle: Telling history people can feel

Most history is told at the wrong scale.

We tend to tell it in the largest units available: centuries, world wars, empires, millions of lives. These units sound serious. They signal importance. But they are not human units.

They exceed what the mind can easily picture and what empathy can reliably reach. We cannot feel a century the way we can feel a day. We cannot imagine millions the way we can imagine one person.

The result is a paradox: the more important the history, the less we feel it.

What is lost is not information, but connection: the ability to recognize something of ourselves in what we are being told.

The Human-Scale Principle

The Human-Scale Principle begins with a simple claim:

History becomes meaningful at the smallest scale where human intention is still visible.

Not at the level of nations.

Not at the level of systems.

But at the level of actions, objects, and voices.

This is not about shrinking history.

It is about entering it at a scale that feels relatable, touchable, and recognizable: the scale at which people naturally pay attention.

The problem this solves

Consider how we usually introduce the Roman Empire. Museums and books often begin with a map: its size, its borders, its chronology. We move on to emperors, legions, and administrative systems. Power expands and contracts. Only later, if time allows, do people appear.

The same pattern repeats across history:

- Ancient Egypt becomes dynasties and monuments

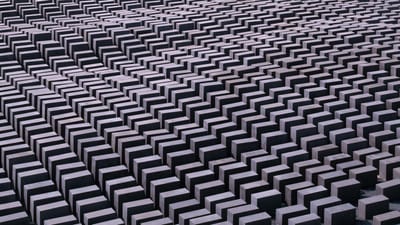

- World War 2 becomes holocaust, D-Day, Market Garden, Stalingrad

- Industrialization becomes forces and outcomes

These narratives ask the audience to care after they understand. They begin with explanation and hope that connection will follow. But attention does not work this way.

Cognitive and educational research shows that connection precedes comprehension. Without attachment, information remains inert. It does not accumulate into meaning.

This is not a stylistic preference.

It is a learning constraint.

What the research shows

Across psychology, education, and museum studies, the findings converge.

Narrative anchoring improves retention.

Information embedded in stories with agents and intentions is recalled more accurately than abstract exposition (Bruner, Actual Minds, Possible Worlds).

https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674029019

Identifiable individuals evoke stronger empathy.

Paul Slovic’s research on psychic numbing shows that emotional engagement decreases as numbers increase; one named person consistently elicits more concern than anonymous masses.

https://www.apa.org/monitor/2015/03/numbers

Object-centered learning deepens understanding.

Museum studies show that visitors engage longer and retain more context when interpretation begins with a single object rather than thematic panels (Falk & Dierking, The Museum Experience Revisited).

https://www.routledge.com/The-Museum-Experience-Revisited/Falk-Dierking/p/book/9781598741636

Delaying abstraction reduces cognitive load.

Cognitive Load Theory demonstrates that starting with complex systems increases learning difficulty; beginning with concrete examples lowers barriers to understanding (Sweller et al.).

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-019-09465-5

In short: people care first, then they understand.

The Human-Scale Principle aligns historical storytelling with how cognition, empathy, and learning actually work.

What Human Scale means and where to start

When I talk about human scale, I don’t mean small or unimportant. I mean something that lets us see a real person acting.

A source works at human scale when it shows:

- someone making a decision

- someone expressing a worry or need

- someone dealing with a result that affects them personally

This doesn’t require a dramatic event or a complete story. It can be a short sentence, a scratched name, a correction, or an object that has clearly been handled and used. What matters is that you can sense intention: that a person was there, trying to do something within limits.

Every historical story contains at least one such moment. That moment is the human-scale entry point. The human-scale entry point is where a reader can first recognize a person before encountering a system.

It usually appears in one of three ways:

- a voice — a letter, a complaint, a promise

- a gesture — a vote, a signature, a scratch

- an object in use — folded, worn, repaired

This entry point is not decoration. It doesn’t serve to illustrate an argument that has already been explained. It is structural.

Once history is entered at this scale, larger frameworks (institutions, economies, empires) can be built outward without losing meaning. The system becomes easier to understand because its human consequences are already visible.

You don’t start with the empire and then look for people.

You start with a person, and the empire slowly comes into focus.

Proof in practice: history at Human Scale

Human-scale history does not argue first. It shows. The following examples are not summaries. They are entry points. Each one is a small trace that pulls the reader into a much larger world.

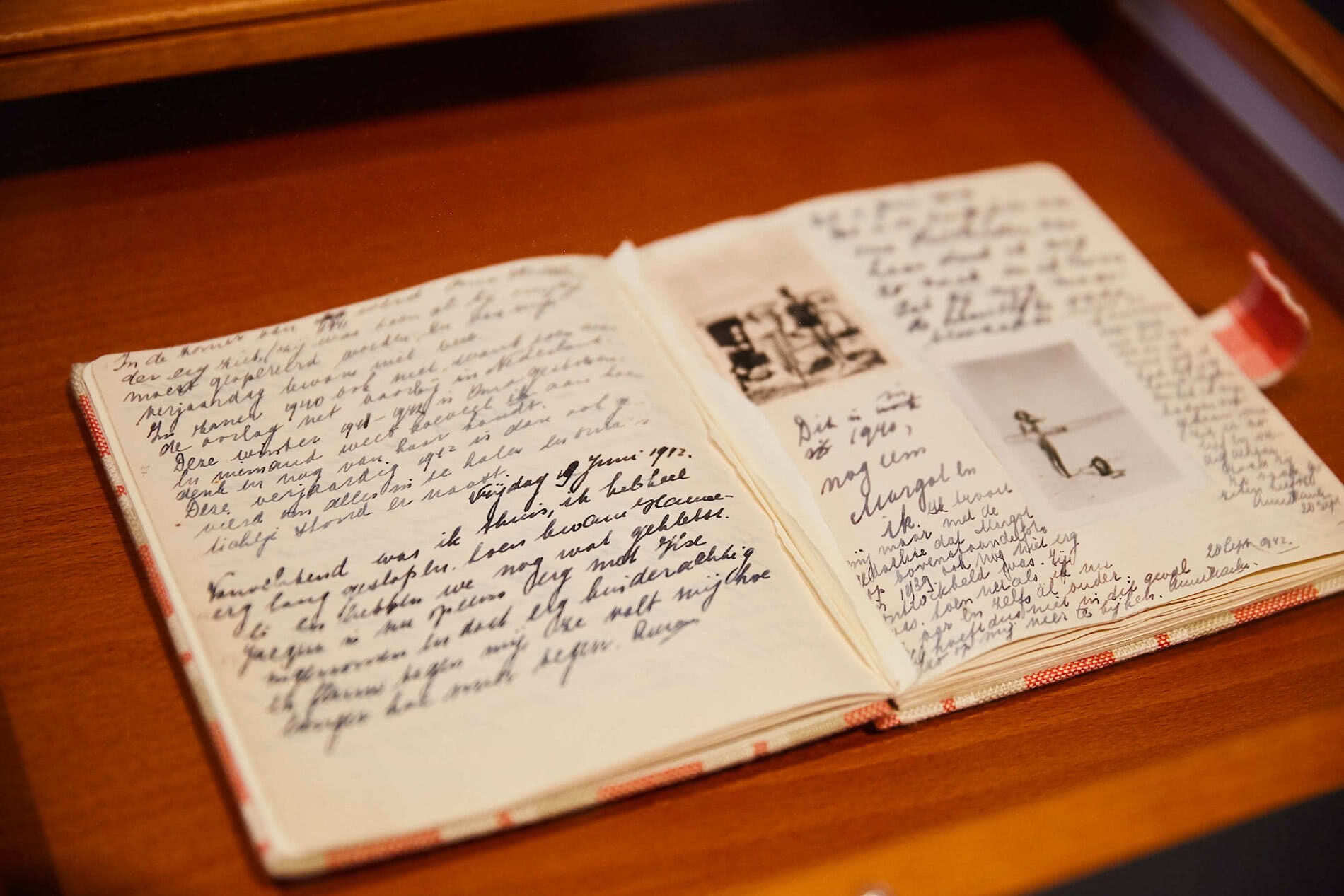

A diary hidden under a mattress

Amsterdam, 1944

“I can shake off everything as I write; my sorrows disappear, my courage is reborn.”

This sentence in Anne Frank's diary does not explain antisemitism, Nazi policy, or genocide. It shows a young person using writing to stay emotionally intact under constant threat.

Only after recognizing her do we begin to understand the system around her: hiding, persecution, betrayal, deportation. The scale of the Holocaust becomes imaginable because it is anchored in one voice.

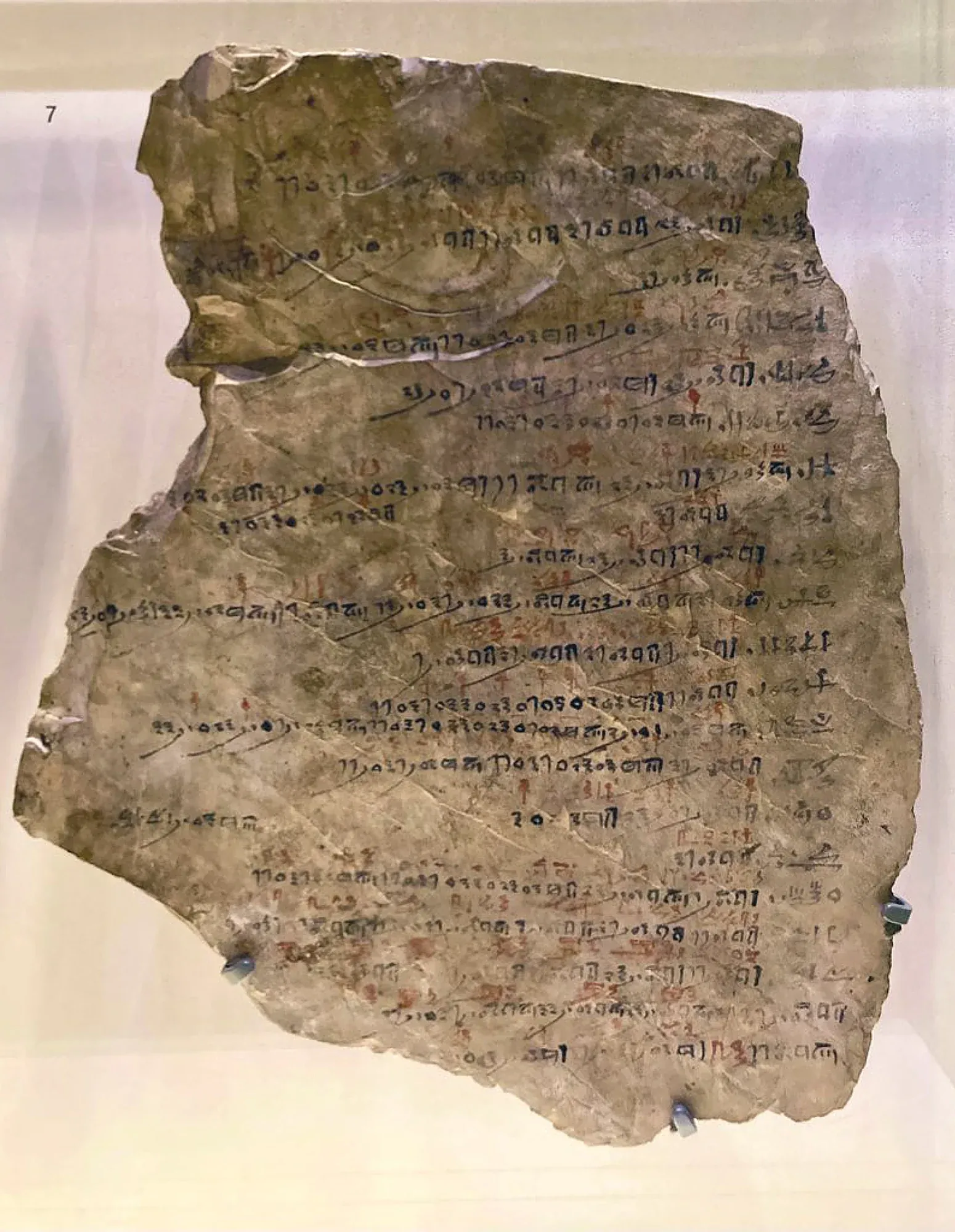

A name scratched into broken pottery

Athens, 5th century BCE

In classical Athens, citizens could vote to exile a political figure for ten years. The vote was cast not on paper, but on broken pottery shards (ostraka) cheap, abundant, and informal.

On some shards, a name appears again and again:

“Themistokles, son of Neokles”

There is no argument here. No explanation of policy or ideology. Just repetition. The political system reveals itself through a scratched gesture.

A Machine Gunner, Years Later

Sidney Williams, World War I veteran, interviewed in 1970

In a television interview recorded more than fifty years after the war, Sidney Williams, a former World War I machine gunner, is asked what he remembers.

He does not describe the battle.

He describes the feeling.

“You didn’t think about it.

You just kept firing.”

The war appears not as strategy or victory, but as repetition and emotional shutdown. From this single memory, industrial warfare becomes understandable: not as an idea, but as something learned by the body and carried for decades.

World War I enters history through what had to be turned off inside one person.

A complaint from a workers’ village

Deir el-Medina, Egypt

Deir el-Medina housed the skilled workers who carved royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Unlike most of ancient Egypt, the site preserves everyday writing... because work required records.

On this 3,200-year-old an attendance sheet is recorded why workers were absent on certain days. The reasons are surprisingly familiar and human. Some workers were away because they were embalming a brother, brewing beer, or had been bitten by a scorpion.

This is not monumental Egypt.

This is payroll. The state becomes visible because a worker speaks.

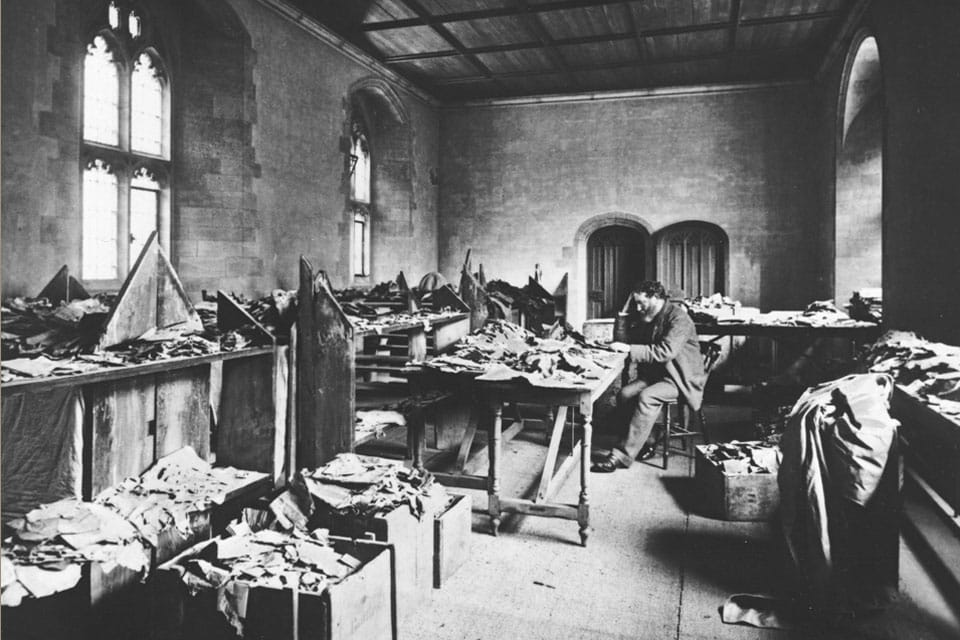

A letter preserved by accident

Cairo Geniza, medieval Mediterranean

For centuries, a synagogue storeroom in Cairo accumulated discarded documents that could not be thrown away because they contained writing. Among them are deeply ordinary letters.

A husband writing to his wife, 11th century:

“I am very anxious about you and cannot sleep.

Let me know how you are and how the children are.”

From this line alone, distance, separation, literacy, and emotional dependency become visible.

A merchant writing to a relative:

“I swear to you, I have nothing left.

I am ashamed to ask again, but I have no choice.”

This is economic history at human scale.

A wife writing about her husband:

“He left me without provision and without explanation.

I do not know what I am to do.”

Law, gender roles, and social protection are present.

The system follows the feeling.

A loaf left in an oven

Pompeii, 79 CE

Not a text. An object.

Bread baked, stamped with the baker’s mark, and left in the oven when Mount Vesuvius erupted. No one bakes bread to abandon it.

The loaf tells us several things at once:

- this was a working day

- food production was regulated and professional

- someone expected to return within minutes

The catastrophe becomes real not because we know the date, but because we see interruption. Disaster gains meaning through unfinished intention.

What these examples prove

None of these fragments were created to explain history. They were created to solve immediate problems: fear, hunger, absence, obligation, routine. They survive not because they were important, but because they were used.

That is precisely why they work.

Each example operates at human scale. We recognize the situation. We understand the worry, the frustration, the expectation of return. These traces turn history from a collection of numbers and abstract events into a world of people with real emotions: people who could have been our neighbors.

This is how the past becomes close enough to matter.

Working at Human Scale: a few principles

The Human-Scale Principle is not just an observation. It is a practice.

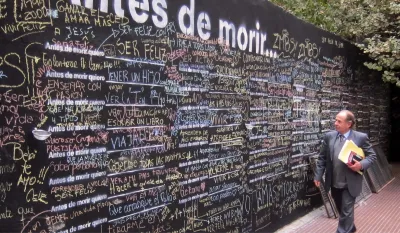

- Start with a trace, not a theme

Begin with something specific: a diary line, a scratched name, a loaf left in an oven... not “The Roman Empire” or “World War II.” - Stay small longer than feels comfortable

Linger on the diary sentence before explaining the Holocaust. Describe the pottery shard before explaining Athenian democracy. - Let objects and voices speak

A folded letter shows care. A repeated name shows determination. A stamped loaf shows routine and expectation. - Expand only after connection

Once the reader cares about the writer, explain the system they lived inside: laws, institutions, empires. - Return to consequence

End by showing what that system meant for this person: exile, hunger, fear, survival.

History becomes meaningful when it is close enough to recognize.

Start with a person.

Let the system reveal itself.

That is the Human-Scale Principle.