The Loop and the Leap

We live in loops.

The content we consume, the news we see, the people we follow. Everything is increasingly shaped by systems that feed us more of what we already like. Facebook shows us posts that echo our beliefs. Netflix lines up more of what we’ve watched. Google shows results around our preferences and data. Algorithms observe, learn, and mirror us back to ourselves, more refined with every click.

These systems don’t just respond to us. They reduce us. They compress complexity into convenience and shape us into more predictable, more profitable, and often, less curious versions of ourselves.

The result is a world that flows perfectly. Until you try to grow.

The logic of the loop

Loops are not inherently harmful. They make things easier. Recommendation systems help us find things we enjoy. Autoplay keeps us entertained without effort. Curated news makes it feel like we’re informed.

But the loop is only helpful when it’s something we can step out of. When it becomes invisible and total, it stops serving us and begins shaping us. The logic is simple: if you liked this, you’ll like that. The more you use it, the tighter it gets.

This is not just about algorithms. It’s about psychology. Human beings prefer what’s familiar. We’re wired to avoid contradiction, ambiguity, and cognitive strain. The loop doesn’t fight that tendency. It exploits it.

What begins as a helpful guide becomes a closed circuit. And in that closed circuit, we stop encountering difference. We stop evolving.

When loops become echo chambers

We tend to think of echo chambers in political terms: filter bubbles that reinforce our ideology. But they also shape how we shop, how we date, how we learn, and how we imagine. Search results, product recommendations, dating apps, curated reading lists… they all reflect our preferences back to us.

Over time, loops don’t just reinforce what we like. They reinforce who we think we are. We start to believe that the things we already know are the only things worth knowing. That the tastes we’ve developed are the only ones that make sense. That the views we hold are simply true.

These systems narrow us quietly. Not through censorship, but through saturation.

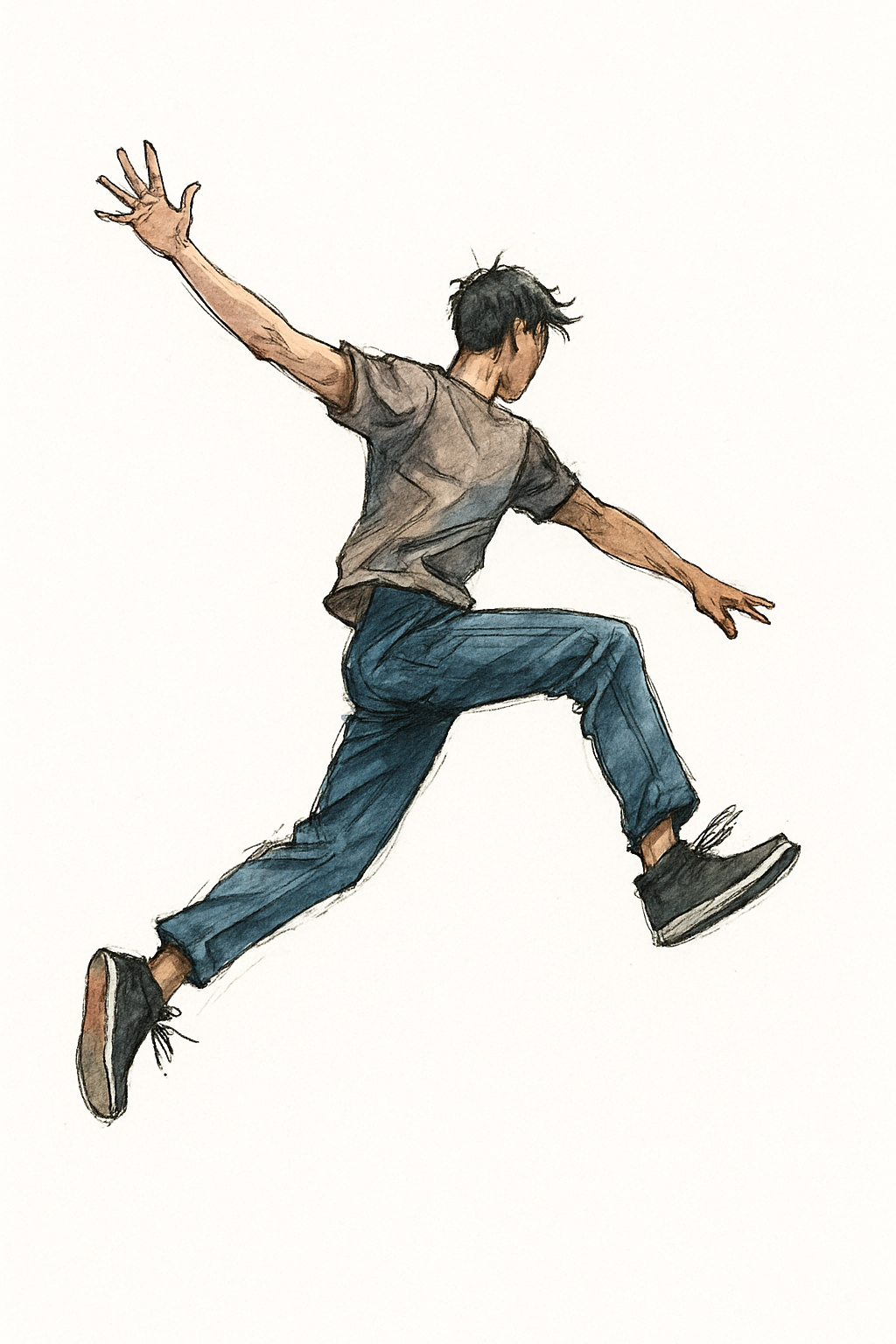

Curiosity is the leap

Curiosity interrupts the loop. It introduces contrast, tension, and ambiguity. It pulls us toward what we don’t know, rather than deeper into what we already do.

A curious mind resists being flattened. It wants complexity. It looks for what doesn’t fit. It holds questions longer than most systems want us to.

Curiosity is what makes us turn the page when we don’t understand. It’s what leads us to sit with a difficult idea rather than scroll past it. It’s not passive. It’s disruptive. And it’s a mark of a mind still capable of growth.

Curiosity is not a UX feature. It’s a value system.

Curiosity builds mirrors and lenses

When we move beyond our default feeds, two things happen.

First, we see ourselves more clearly. Our habits, biases, and blind spots come into focus. This is the mirror. It helps us realise how small our world has become and how we’ve unknowingly helped make it that way. It’s uncomfortable, but necessary.

Second, we see the world more clearly. We encounter new perspectives, histories, aesthetics, and frameworks for thinking. This is the lens. It doesn’t just offer new content: it expands our capacity to perceive, imagine, and relate. It gives us back the full range of being human.

These aren’t just personal benefits. They’re systemic ones. Curious individuals build better conversations. Curious teams build better products. Curious cultures create space for progress, not just performance.

Moral ambition and the responsibility to design for curiosity

When we design systems that shape how people see the world, we are not just building products: we are setting perceptual boundaries. We are deciding what is seen, what is ignored, what feels true, and what is never even encountered. That is power. And with power comes responsibility.

This is where moral ambition matters.

Designing for curiosity is not just about offering novelty or intellectual appeal. It is about safeguarding the conditions for thought itself. Curiosity supports reflection. Reflection supports understanding. Understanding supports humanity. In this sense, facilitating curiosity is not a design preference: it is a human obligation.

Some companies hint at this. Alphabet (Google) speaks about "fueling curiosity" and "unlocking opportunity." Their internal workshops on moral imagination reflect an awareness of their influence. Meta (Facebook), too, speaks about building connection and empowering communities. But these ambitions are often at odds with the systems they maintain: systems optimised for engagement, not depth; for retention, not growth.

Both companies have been criticised for reinforcing filter bubbles, accelerating emotional polarization, and monetising attention in ways that erode mental well-being. These are not technical glitches. They are the result of design decisions made in the absence of moral ambition.

Designing for curiosity requires tension. It asks systems to resist the easy metrics of time-on-site and instead support time well spent. It asks us to accept slower, messier outcomes in exchange for wiser, freer users.

If we’re building systems that reach billions of people, we cannot pretend neutrality. Every design is a set of values in motion. The question is no longer: Can we personalise everything? It’s: Should we?

And what happens when we don’t leave any room to be surprised?

The leap is already working

Some organisations have already made curiosity part of their design and been rewarded for it.

- Wikipedia’s “Random Article” button offers no relevance, no optimisation… just serendipity. It’s beloved because it asks nothing of the algorithm and everything of the mind.

- Spotify’s “Discover Weekly” doesn’t just echo what you already like. It blends familiarity with well-curated novelty. It’s one of the platform’s most engaging features. Why? Because people don’t just want more of the same. They want to be surprised, when it’s done with care.

- The New York Times Opinion section publishes voices across political lines. It frustrates its readers regularly. It also builds trust. It creates space for complexity in a media landscape addicted to simplicity.

Each of these examples shows the same thing: curiosity can thrive when it’s designed in, signalled clearly, and respected as part of the experience.

Anchors for designing with curiosity

If we want systems to do more than keep people inside themselves, we need to build for something different. Below are some design principles that make space for the leap (I would love to hear your thoughts on them).

- Reveal the loop — Make the algorithm visible. Let people see how their behavior shapes what they’re shown and how narrow it’s become. Transparency creates awareness. Awareness creates choice.

- Build contrast by design — Don’t just reinforce preferences. Intentionally surface content that disrupts the pattern: different genres, viewpoints, styles, or scales. Contrast is how systems teach, not just please.

- Interrupt the rhythm — Design for friction, not just flow. Let things end. Break autoplay. Insert moments of pause, silence, or reflection. Cognitive space is essential for curiosity to land.

- Track and reward divergence — Don’t just measure stickiness. Measure deviation. Highlight when users explore outside their usual categories, and reward those moments. Exploration should be seen as success.

- Seed serendipity — Inject randomness, gently. Add “surprise me” modes, unpredictable connections, or lateral suggestions. People don’t always know what they’re looking for, until it finds them.

- Design for expansion — Stop optimizing for who the user has been. Start designing for who they could become: curious, wiser, more nuanced. Every system is a mirror. Make yours a doorway.

This is a choice

The loop is not fate. It’s a decision. One we make every time we build, write, code, teach, or publish.

We can design systems that train people to consume efficiently, or systems that help people think expansively.

We can serve comfort, or we can support growth. But rarely both.

If we don’t deliberately protect curiosity, we risk designing it out. It will not thrive by accident. It must be nurtured, invited, and made visible.

That responsibility belongs to all of us.

People may default to comfort, but they crave meaning. They scroll past noise, but they stop for insight. They remember what made them think, not what made them click. The success of books, podcasts, deep conversations, and even long-form content in a short-form world proves this: people don’t just want curiosity, they're starved for it.

Design for curiosity, and you don’t just shape better users. You shape better humans.

And it starts with the choice to stop looping and start leaping.