The Poetics of Place: The Work of Mariam Issoufou

Look closely at the places that stay with you.

They are rarely the loud ones.

They don’t announce their purpose. They don’t explain themselves. They don’t rush you. They allow life to arrive slowly... and then they adapt to it.

This is the level at which the work of Mariam Issoufou operates.

Her buildings teach us something subtle but important: place is not produced by intention alone, but by alignment. Alignment between climate and form. Between social habits and spatial rules. Between what people already do and what architecture quietly enables.

What her work reveals, when you observe carefully

1. Climate is not a problem to solve, but a structure to think with

In Issoufou’s projects, heat, shade, wind, and dust are not neutral background conditions. They actively shape space. Courtyards are not aesthetic choices; they are thermal devices and social condensers at once. Movement slows where shade thickens. Gathering happens where the climate allows it. Architecture follows these logics instead of fighting them.

Learning: When we design against climate, places become fragile. When we design with it, places become legible.

2. Social life happens in gradients, not zones

Her buildings rarely separate functions cleanly. Instead, they rely on transitions: thresholds, edges, semi-open spaces, in-between rooms. These allow people to negotiate presence (to join, to observe, to withdraw) without having to decide once and for all.

Learning: Connection doesn’t happen in designated “social spaces.” It happens in spaces that allow hesitation.

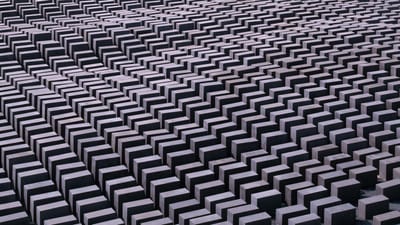

3. Meaning emerges through repetition, not explanation

Issoufou’s architecture does not tell you what it stands for. It lets meaning accumulate through use. A library becomes a meeting place because people return. A courtyard becomes civic because it is crossed daily. Memory does the work that signage and symbolism often try to do too quickly.

Learning: Places gain depth when they are allowed to be discovered slowly.

4. Materials are chosen for their future, not their image

Local materials are not deployed as markers of authenticity. They are chosen because they can age, be repaired, and be understood by those who live with them. These buildings anticipate touch, wear, and change.

Learning: Sustainability is strongest when it assumes maintenance, not permanence.

5. Architecture can be generous without being expressive

Perhaps the most striking quality of her work is its restraint. Nothing is asking for attention. The buildings do not perform. They host. They wait for life to complete them.

Learning: The most meaningful places often come from designers who resist the urge to speak too loudly.

What stays with me most in her work is its pureness.

The simplicity.

And at the same time, the deep connectedness: to people, to climate, to everyday life.

Nothing feels forced. Nothing is trying to prove a point. The buildings don’t compete with their surroundings; they belong to them. They feel confident enough to be calm. Patient enough to let life complete them.

That is rare.

What this teaches beyond architecture

Seen through this lens, Issoufou’s work is not only relevant to architects. It offers lessons for anyone working with places, experiences, institutions, or public life.

1. Clarity comes from restraint, not reduction

Her buildings are simple, but never simplistic. What is absent has been deliberately removed, not ignored. This kind of clarity only appears when a designer knows what not to touch.

2. Belonging is spatial before it is emotional

People feel connected not because a place tells them they belong, but because it accommodates their bodies, rhythms, and habits. Her architecture makes room for this quietly, without naming it.

3. Context is not something to reference. It is something to collaborate with

Climate, materials, and social customs are not constraints to work around. They are active partners in shaping form. The building emerges from that conversation.

4. Good places don’t resolve life: they hold it

Her work doesn’t aim to optimise behaviour or fix social complexity. It accepts contradiction, overlap, and change. Spaces remain open enough for life to unfold on its own terms.

5. Durability is cultural before it is technical

What lasts is not just what is well-built, but what people recognise as theirs. Repairable materials, familiar techniques, and adaptable layouts create emotional ownership over time.

6. Attention is a design material

Perhaps the most important lesson: attention precedes form. The patience to watch, listen, and wait shapes the architecture as much as concrete or brick.

Her architecture suggests something quietly radical:

connection is not something we create.

It is something we make space for.

And perhaps the most valuable question her work leaves me with is not about buildings at all, but about how we approach the world around us:

What would change if we trusted everyday life enough to design around it, rather than trying to improve it first?