TWIL #12: From Unspoken Stories to Natural Borders

Writing a TWIL is one of my favorite moments of the week. It pushes me to look more closely at the things I’ve come across and reminds me just how much interesting stuff a single week can hold, if you’re paying attention. The news cycle, especially from the U.S., always tries to dominate the spotlight (tariffs, anyone?). But this week, I chose to follow my curiosity elsewhere.

The unspoken story

In an interview I came across (see video below), Quentin Tarantino pointed out two small but unforgettable details in his films: the rope burn around Aldo Rain’s neck in Inglorious Basterds, and the mysterious briefcase in Pulp Fiction.

He shows them to us in his story, plain as day, but never explains them.

And that’s the magic.

By withholding the full story, he leaves the door cracked open. Just enough for our curiosity to sneak in. And once it’s in, it starts working overtime: How did he get the burn? What’s in the chest? We start filling in the blanks ourselves. Each person creates their own version of the story.

In a world that so often rushes to explain everything, there's real power in mystery.

Curiosity thrives in the spaces between the known. It turns passive viewers into active storytellers. And maybe that's the secret sauce behind Tarantino's staying power: he trusts the audience to wonder.

I’ve found myself using this clip as a metaphor all week: in conversations about storytelling, creativity, even relationships. It’s a perfect example of how curiosity works. How leaving something unsaid can sometimes say the most.

In a world obsessed with answers, there’s power in holding a little mystery.

So, what might happen if you left just a bit more unsaid? What blank spaces are you inviting others to fill?

A different view of Europe

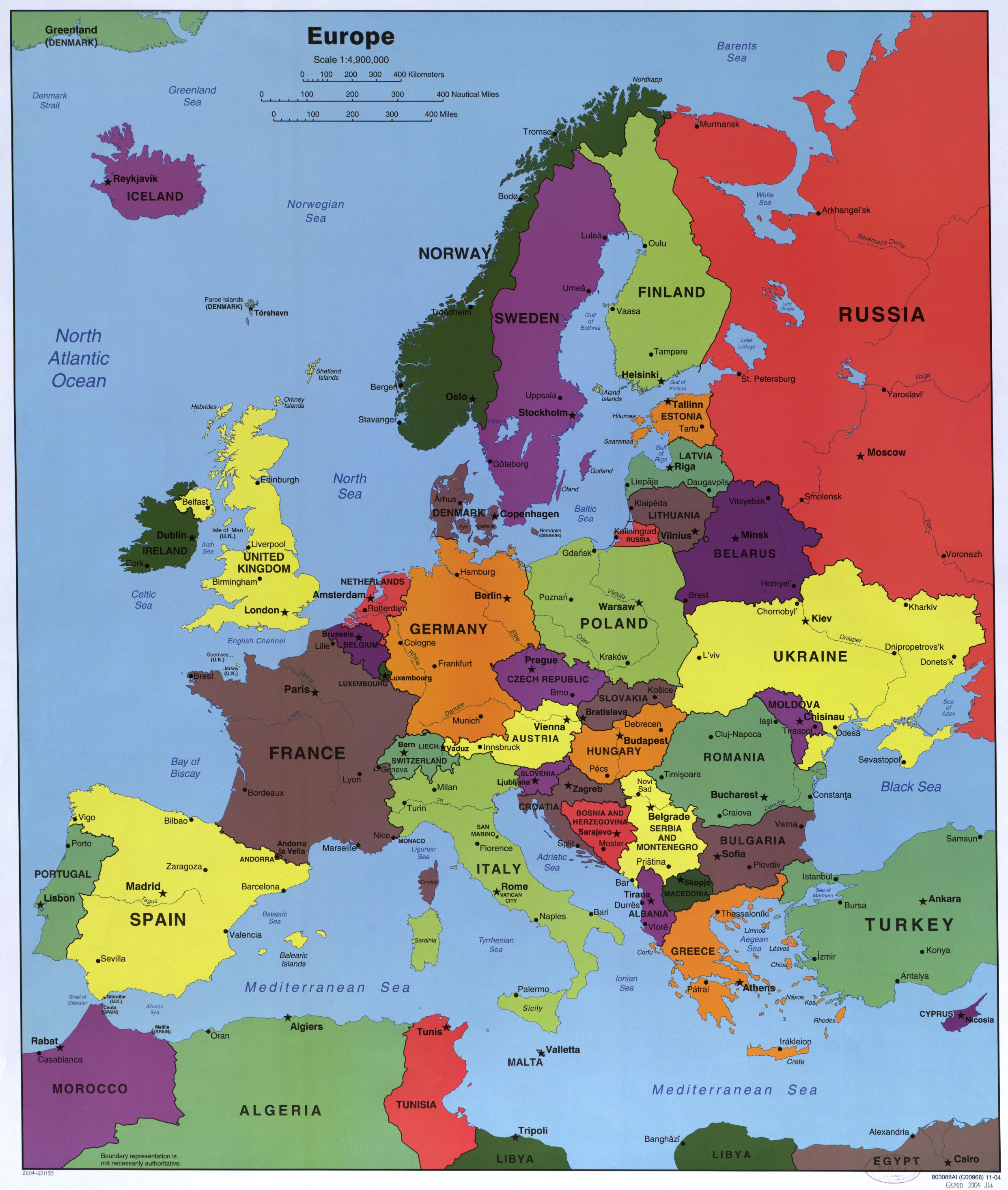

I love maps like this one.

Not the kind that just mark borders and cities, but the kind that lets you feel the shape of the land. This topographic map of Europe shows something deeper: the textures of history, culture, and movement.

I’ve found myself returning to this image again and again recently. In conversations, in thinking, even just in quiet moments of curiosity. It doesn’t just show where things are… it helps you understand why things happen the way they do.

So I started asking questions. Some I already had half-answers to. Others surprised me.

The School of Curiosity is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a subscriber.

How did the shape of the land quietly shape everything: from where empires rose to where your ancestors settled?

It has. Over and over again.

Rivers didn’t just carve through the land. They carved the future. The Nile birthed Egypt. The Tigris and Euphrates cradled Mesopotamia. The Danube and the Rhine became highways for Rome, then borders for barbarians, then flashpoints for empires.

Mountains? They were more than scenery. The Alps kept Hannibal at bay (though not before he crossed them with elephants). The Pyrenees marked the edge of Muslim expansion into Europe. The Himalayas sealed off India, creating its own world of kingdoms, cultures, and gods.

Flat plains? Perfect for farming and for fighting. The North European Plain has seen everyone from Roman legions to Panzer tanks. It offers no natural defense, so whoever controls it needs to either keep marching or keep fortifying.

Fertile valleys whispered promises of harvest. The Po Valley in Italy, the Loire in France, the Ganges in India… all turned seeds into settlements, and settlements into cities, then into capitals of kingdoms and causes.

The Roman Empire didn’t just sprawl randomly across a map. It moved with the land. It hugged coastlines where ships could resupply. It climbed through valleys, followed the contours of rivers, and stopped at natural walls. Forests too dense, mountains too high, deserts too vast. Even Hadrian’s Wall was less a line in the sand and more a nod to where nature said, "no further."

Later came the Ottomans, the Habsburgs, Napoleon. Each marching with a map not just of politics, but of geography. The land told them where they could go. And where they could not.

And your ancestors? They weren’t just picking pretty spots. They were listening to the land. “Here, the soil is rich.” “Here, the river runs wide and steady.” “Here, the winds aren’t cruel in winter.”

How has terrain influenced language and culture?

The Balkans, the Caucasus, the Carpathians: more than just mountain ranges, these are natural dividers and cradles of complexity. Rugged terrain made movement difficult, isolating communities just enough for unique languages, customs, and beliefs to take root and evolve independently.

That’s why, in the Caucasus, you can find dozens of languages spoken within a relatively small region. Many with no relation to each other. Or why the Balkans remain, even after centuries of shared history, a richly woven patchwork of nations, religions, and traditions.

Then I turned my attention homeward.

What does it mean to grow up on flat land?

The Netherlands, like much of northwestern Europe, is the opposite of mountainous. Flat. Low. Open. With rivers that invite travel and coastlines that welcome trade. Here, movement is easy. Cultures have overlapped for centuries.

From the Hanseatic League to the Dutch Golden Age, the geography of openness shaped a culture of exchange. And even now, I think you can feel it: a certain cultural permeability. An ease with adopting, adapting, absorbing. Ideas flow here, just like the Rhine and the Maas.

Where mountains preserve identity, flatlands invite conversation.

What does the map say about conflict and defense?

Here’s where things got even more interesting. I started to look at the map from a strategic viewpoint. Not just as geography, but as a playbook.

Take Russia. On a political map, Europe looks like a flat puzzle of borders. Clean lines, clear labels. But the moment you switch to a topographic or terrain map, everything changes. You see what armies see: ridges, rivers, bottlenecks. Natural barriers and forced pathways. Places where you dig in and places where you're exposed.

And then it hits you: this is why history keeps repeating itself.

Napoleon and Hitler both invaded Russia through the North European Plain, moving eastward across modern-day Poland, Belarus, and into western Russia: a flat, open corridor with few natural obstacles. It’s the most direct, and most dangerous, route into the Russian heartland.Why? Because it’s flat. No mountains. No major rivers to slow you down. Just wide-open land, perfect for tanks… and disaster. That same openness means defenders have no natural barriers either. Which is why Russia has always pushed outward, trying to create buffer zones. From the Tsars to Stalin, it’s been the same instinct: defend with depth.

Maps invite you to think differently. To notice what isn’t said. To ask better questions. And that, to me, is what curiosity is all about.

Where does your eye go first? And what do you start seeing differently when you shift your view?

What else?

- Instant noodles were invented after WWII to combat food shortages, but now they’re considered a luxury in some prisons.

- The invention of the bicycle helped popularize women's rights in the late 19th century. Susan B. Anthony even said bicycling “has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.” It gave women unprecedented mobility, freedom, and a reason to ditch restrictive clothing like corsets and long skirts.