TWIL #13: From Fast Food to Collapsing Civilizations

And just like that, another week has flown by packed with fascinating meetings, conversations, and unexpected rabbit holes.

Between all the deep dives and side quests, I also got a nice surprise this week: an email and a kind comment about the newsletter. I know people are reading, even if it’s mostly quiet on the reply front… but these two messages made my day. And if anything ever sparks a thought: feel free to drop me a line.

Fast Food proximity: the silent saboteur of public health

I came across a post on LinkedIn the other day about a planned “Food Village” in Duiven, the Netherlands. A new development packed with fast-food chains. What struck me wasn’t just the usual clash between convenience and health, it was the context: Duiven already struggles with above-average rates of overweight and obesity.

The post stuck with me, so I decided to dig a bit deeper. That’s when I came across a large Dutch study that made the whole issue hit harder.

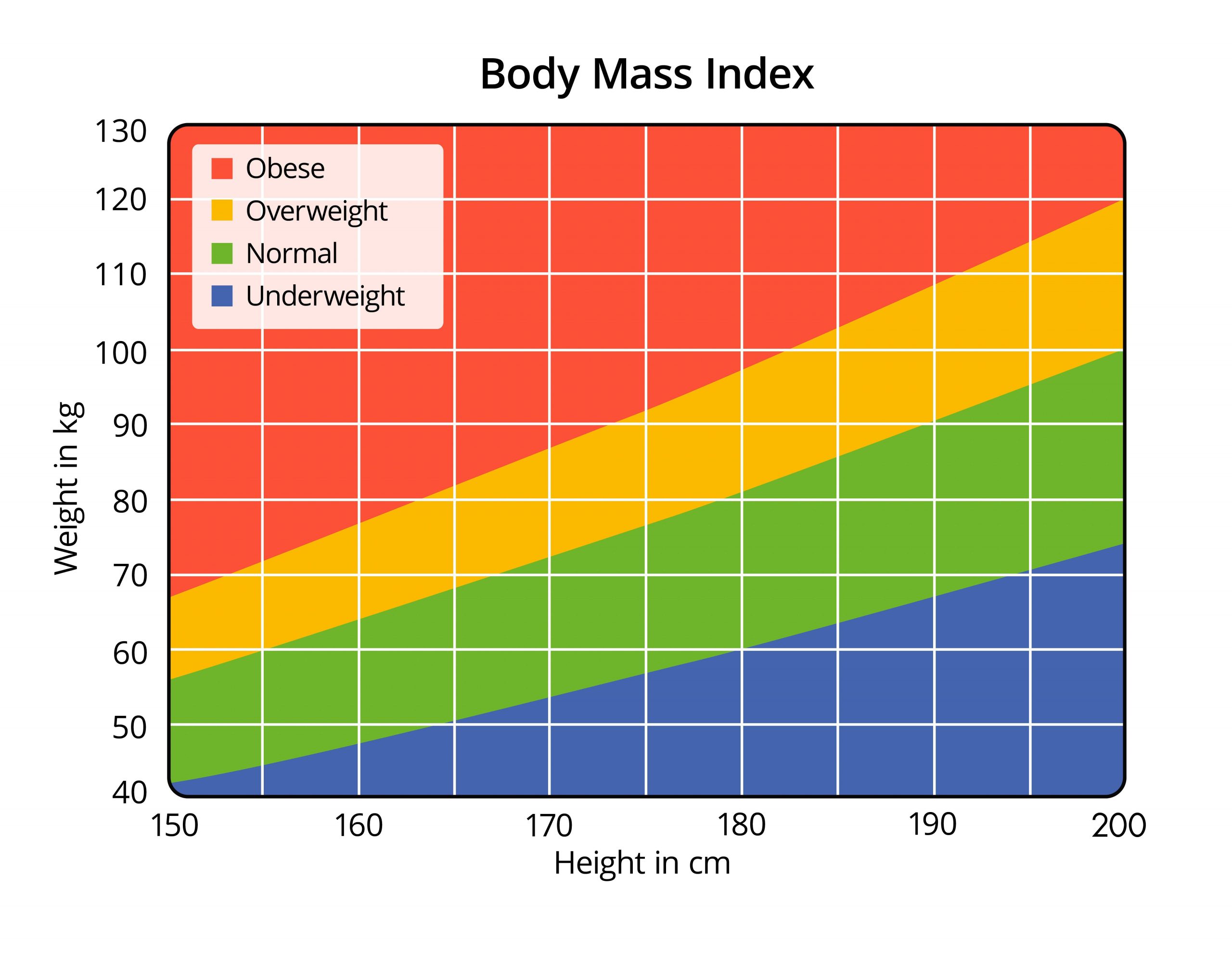

Researchers working with data from over 147,000 adults in the Lifelines Cohort Study found something striking: just living closer to fast food is linked to a higher Body Mass Index (BMI). Not because people lack discipline, but because our environments shape our behavior—quietly but powerfully.

Here’s what they found:

- In urban areas, people with two or more fast-food outlets within 1 km had BMI scores 0.32 units higher than those with none nearby.

- In rural areas, five or more outlets within that same range meant a 0.23-unit increase.

What does that mean in practice? For someone who’s 1.75 meters tall (5'9"), a 0.32 increase in BMI equals roughly 1 kg (2.2 lbs).That might sound minor… but across entire communities, it’s a big deal.

Even more concerning? The effect was strongest in low-income neighborhoods, even when healthy options were available. So it’s not just about “offering choice.” It’s about proximity, price, and marketing. The unhealthy option is often cheaper, faster, and easier and that’s the problem.

This brought me right back to that Duiven post. A town that’s already struggling with weight-related health issues is about to be flooded with fast-food logos all framed as meeting “consumer demand.” But when demand is engineered by frictionless access, we’re not just selling burgers. We’re designing health outcomes.

In the Netherlands we’ve gotten good at investing in bike paths, green spaces, and community fitness programs. But when fast-food franchises dominate the spaces next to schools, parks, and train stations, those investments start to unravel.

We need to be honest: this is health-washing. You can’t pave cycle lanes with one hand while handing out fast-food permits with the other.

If we want real health equity, we have to design for it. That means making the easy choice the healthy one, not just the cheapest or most convenient.

An Encyclopedia of Unknowns

Fabian Hemmert this week shared Wikenigma with me. A sort of anti-encyclopedia that collects what we don’t know instead of what we do.

It’s a beautifully simple idea: an invitation to explore the gaps in human knowledge, from why we blush to how language began. It’s a perfect curiosity starter. I found myself clicking around, diving into mysteries we rarely stop to question. Definitely worth a wander. Thanks Fabian!

The 4.2-Kiloyear event: when climate change sends civilization into chaos

While writing pieces for some of my previous TWILs, I stumbled across a mention of something called the 4.2-kiloyear event. I didn’t have time to dive into it then, but the name stuck with me. It sounded both oddly specific and vaguely apocalyptic. So this week, I finally set aside time to look into it, and wow, it turned out to be one of those “how did I not know about this already?” moments.

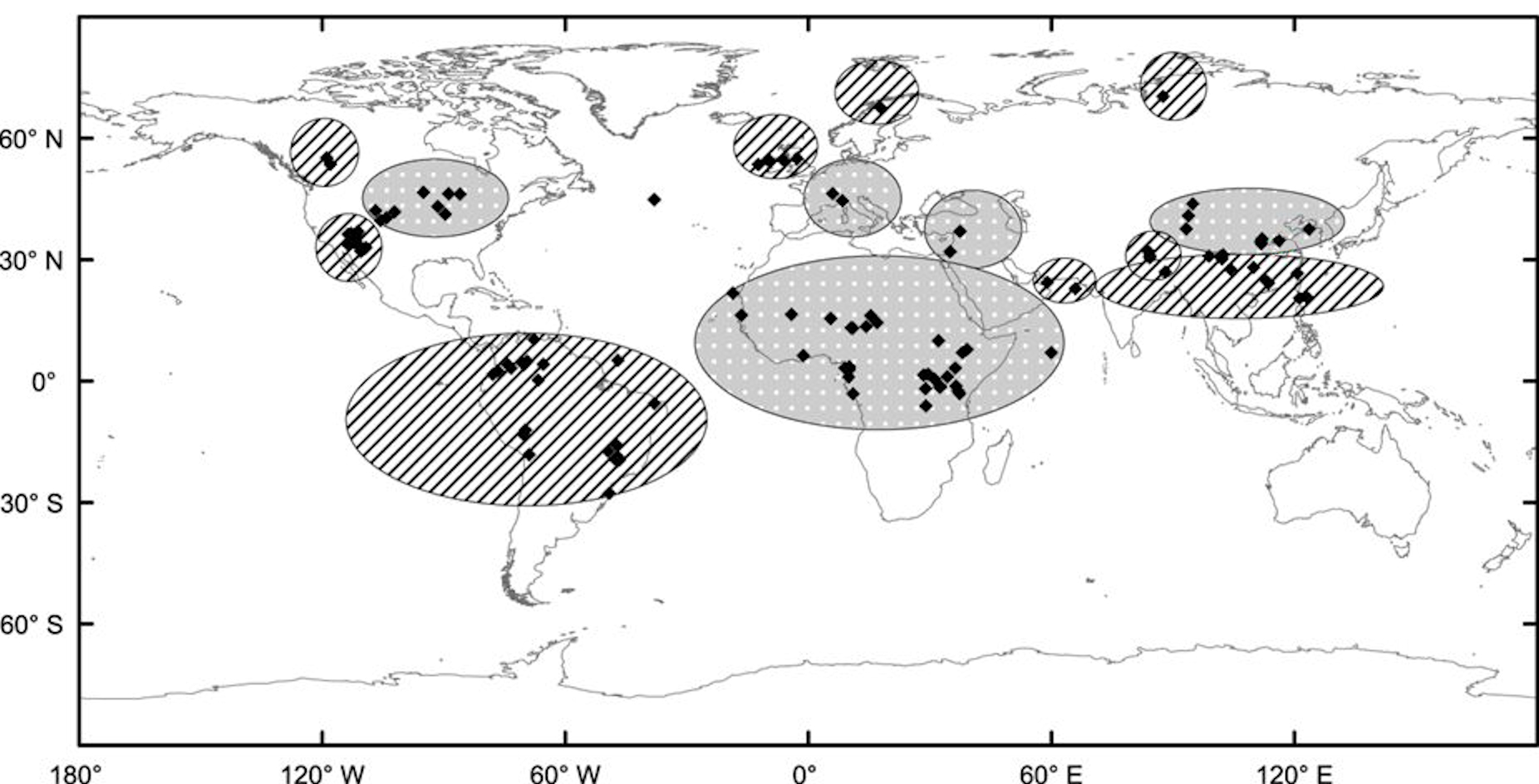

Turns out, around 2200 BCE (roughly 4,200 years ago) a global climate anomaly disrupted weather patterns across multiple continents and possibly triggered a cascade of collapses in some of the world’s earliest complex societies.

What happened?

This was a period of sustained drought, shifting rainfall patterns, and regional cooling, likely caused by changes in ocean circulation or solar activity (the jury’s still out). The event lasted for decades to centuries in different regions. But its real legacy lies in how many civilizations struggled, or failed, to adapt.

Here’s a quick rundown of what was happening around the world at the time:

- Egypt: The Old Kingdom collapsed, ending the era of pyramid-building. Egypt entered the First Intermediate Period, a time of political decentralization and social unrest.

- Mesopotamia: The Akkadian Empire, often considered the first empire in history, collapsed after just a century of dominance. Archaeological layers show widespread abandonment and signs of famine.

- Indus Valley Civilization: Urban centers began to decline. There's evidence of drying rivers (like the Ghaggar-Hakra, possibly the mythical Saraswati) and a move away from planned city living.

- China (Liangzhu Culture): The sophisticated jade-working Liangzhu culture in the Yangtze Delta suddenly disappeared. Some researchers link this to extreme flooding following periods of drought… sort of a climatic whiplash.

- The Levant and Eastern Mediterranean: Settlements shrank or were abandoned. There's evidence of migrations and a sharp decline in trade and cultural exchange.

- North America and South America: Less is known, but some lake sediment records suggest significant aridity in parts of the Americas, too.

Why it’s fascinating (to me, at least)

I love that this isn’t just about history… it’s about patterns. It’s eerie and humbling to realize that climate instability isn’t a new challenge. Civilizations long before us faced environmental shocks, and their ability (or inability) to adapt shaped the course of human development.

Also, there’s still a lot of mystery. Interestingly, a recent study from Northern Arizona University suggests that while the 4.2 ka event did occur, its impacts may not have been globally catastrophic as previously thought. The researchers found that abrupt changes in temperature and rainfall were common at local scales throughout the Holocene, and globally coherent events were rare. This calls into question the use of the 4.2 ka event as a global geologic marker and provides a cautionary tale in interpreting local climate changes as globally significant.

Magna Carta

I was watching Masters of the Air on Apple TV+ when one of the characters casually mentioned the Magna Carta, which sent me down a mini rabbit hole.

In case you’re rusty on it: the Magna Carta was a charter signed in 1215 by King John of England, forced by rebellious barons to acknowledge that even the king wasn’t above the law.

While often called the foundation of democracy, it’s not quite that heroic at first glance:

- It was mostly about protecting the interests of wealthy landowners, not ordinary people.

- It was annulled almost immediately and sparked more conflict than it solved.

- Most clauses were about feudal rules and taxes, not freedom or rights.

But here’s the twist: over the centuries, a few key ideas (like due process and legal limits on power) took on symbolic weight. Later generations used it as legal and political inspiration, especially in the development of constitutional government in Britain and the U.S.

So no, it wasn’t born a beacon of liberty, but it became one over time.

See you next week! 🌞