TWIL #17: From Circumnavigation to Vanilla Pollination

Magellan’s voyage around the globe

Currently I am been reading Roger Crowley’s Spice: The 16th-Century Contest that Shaped the Modern World (highly recommend all his books: his writing pulls you right into the past), and this week I learned about Magellan’s expedition: the first circumnavigation of the world.

I’d vaguely heard of it before. But I had no idea how wild, how brutal, and how unlikely it really was.

Here’s what blew me away:

In 1519, five ships and 270 men left Spain, chasing a western route to the fabled Spice Islands. They sailed into the unknown with maps full of blank spaces and guesses. They didn’t know how wide the Pacific was. They didn’t know if the continents connected. And yet… they went.

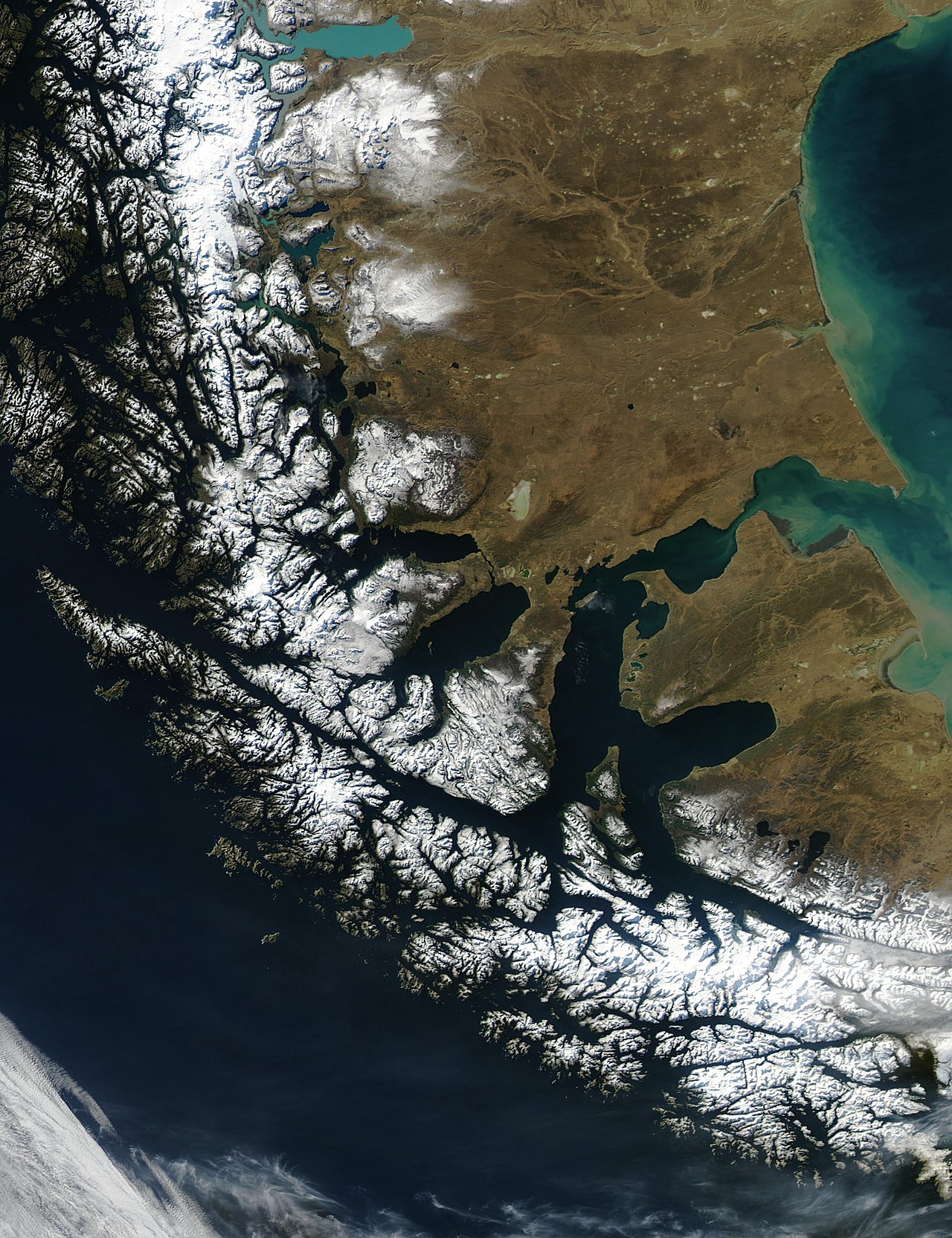

It took over a year of hardship just to find a strait at the tip of South America. In the end they found one, which we nowadays call the Strait of Magellan (Chili) (location).They faced mutiny. Storms. Ice. Weeks trapped in twisting channels, unsure if the passage led anywhere at all.

And then came the Pacific.

They thought it would be a quick crossing. It wasn’t. The Pacific was unimaginably bigger than they realized: thousands of miles wider than their maps had guessed.

For 99 days, they sailed across empty ocean without sight of land.

They ran out of food. Ate sawdust. Boiled leather. Chewed the soles of their shoes. Men died of scurvy, their gums rotting until their teeth fell out. (Though the officers fared a little better, unknowingly protected by the fruit preserves in their jam. They didn’t know it was vitamin C saving them.) Every sunrise must have felt like a punishment.

By the time they reached the Philippines, they were skeletal, half-mad with hunger.

And even then, the danger wasn’t over.

Magellan was killed in a local conflict he misunderstood… stepping into a complex regional power struggle he thought he could control. He led a handful of men into battle against 1,500 warriors, convinced of his technological and moral superiority. It wasn’t enough. He underestimated both their strength and their resolve. And it cost him his life. His surviving crew fled. One ship was captured. By the time they limped back to Spain in 1522, only one ship, Victoria, and 18 men remained.

From five ships and 270 men… to 1 ship and 18 survivors.

It’s staggering.

But beyond the sheer hardship, something else struck me:

they didn’t just struggle against the sea. They struggled against their own assumptions.

They arrived everywhere with a conquistador mindset: dividing the world into conqueror and conquered, Christian and heathen, trade and tribute. But the world didn’t fit their categories. They underestimated the complexity of the places they landed: the alliances, rivalries, and long-established networks of trade and diplomacy across the Pacific.

In the Philippines, Magellan believed that converting one ruler would bring the islands under his banner. He imagined a chain of submission. But he didn’t see the deeper political fractures. When he tried to force a rival chief, Lapu-Lapu, to kneel he was killed.

Their maps weren’t just wrong geographically.

They were wrong culturally.

They circled the planet. But in many ways, they never left their own point of view.

And that’s what made me wonder:

What journeys are we making today, convinced we’re discovering something new… when we’re really trapped inside our own assumptions?

Maybe it’s AI, trained on our own biases.

Space, while we neglect Earth.

Climate solutions, without seeing nature’s complexity.

Vanilla isn’t boring at all

This week I learned that vanilla is the world’s second most expensive spice after saffron. Why? Each vanilla orchid must be pollinated by hand within a 12-hour window, since the natural pollinator (a tiny bee) only lives in parts of Mexico. Every pod is a tiny miracle of timing and patience.

So next time someone calls vanilla “plain”… they’ve got it backward. It’s secretly the diva of flavors.

Eye for an Eye vs Marcus Aurelius

I’ve been reading about Stoicism lately, and I really like it. Not just as a philosophy, but as a mindset. It has deep roots, going back to ancient Greece and Rome, practiced by thinkers like Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius.

At its core, Stoicism teaches a few simple but powerful principles:

- Focus only on what you can control

- Accept what you cannot control

- Cultivate inner strength and virtue

- Respond to challenges with calm and reason

That is why Stoicism has been embraced by special forces soldiers, professional athletes, and leaders in high-pressure fields. It offers a way to stay composed, resilient, and steady, no matter what chaos or hardship you face.

The Stoics had a pretty clear-eyed (and honestly, sometimes a bit gloomy) view of life. They believed life is unpredictable, often unfair, and full of setbacks. Their solution? Don’t get too attached, don’t get too angry, don’t expect too much. I admit, a little bleak. But also freeing. They wanted to build emotional strength by letting go of what we can’t control. And holding firm to what we can.

One line from Marcus Aurelius keeps echoing for me:

“The best revenge is to be unlike him who performed the injury.”

I find that powerful. It’s a call not to mirror harm, not to let someone else’s bad behavior shape who we become. To stay true to ourselves, even when wronged.

That’s not our natural instinct. Most of us know “an eye for an eye” as the default: a call for balance. We think of it as biblical (it is in the Old Testament), but it actually goes back further, to the Code of Hammurabi, one of the oldest legal codes. It was probably designed to limit revenge, to stop punishments from escalating. But even then, it kept harm alive: hurt met with hurt, forever trading blows.

And we still live by it, in small and large ways. We get even. We retaliate. We mirror harm, believing it restores balance. Like the current tension between Pakistan and India: each side responding with equal measure, each action answered by the other, until what began as a reaction becomes a cycle, building pressure with every turn.

But Marcus offers a harder path: to stop the cycle. To stay better, even when it feels easier to strike back. It’s not an easy answer. It’s certainly not the quick one. But maybe it’s the only way that actually ends the cycle.

And maybe it offers something more. Because in refusing to mirror harm, we’re not just stopping a reaction. We’re choosing who we want to be. We’re saying: I won’t let someone else’s actions shape me. I won’t become their reflection. I’ll define myself by my own values, not theirs.

Thursday I was listening to a news podcast. A journalist I really respect was reporting on a tense international situation. She said, almost without question, that now “the leader of Pakistan now has to show strength and respond.” It hit me: even thoughtful people, even voices I admire, automatically assume that retaliation and show of equal strenght is the only possible response. That strength means matching harm with harm. That “an eye for an eye” is the natural path forward.

But Marcus challenges that. He suggests strength might look different. That sometimes true strength is refusing to be drawn into the same patterns.

And I wonder: what would that kind of clarity bring… not just in our personal lives, but in leadership, in politics, in the way nations respond to each other?

Anyway… read a book on stoicism! Here is an easy one to start with: