TWIL #19: From Cognitive Debt to New Perspectives

Every Sunday, I share a few of my learnings, reflections, and curiosities from the week. Things I stumbled upon, things I questioned, things that made me look twice. It’s not about being right or complete… it’s about noticing, wondering, and learning out loud.

Thanks for reading. I hope it sparks something for you too.

Cognitive debt

So, last week, the Chicago Sun-Times published a summer reading list. Pretty normal stuff, except it included books that don’t exist.

Titles like Tidewater Dreams by Isabel Allende and The Last Algorithm by Andy Weir sounded enticing, but readers quickly discovered that while the authors are real, the books are entirely fabricated. The paper later confirmed the list was created using AI and slipped into print without proper editorial oversight.

This moment offers a perfect, and troubling, example of what John Willshire recently described as Cognitive Debt.

“Cognitive Debt is where you forgo the thinking in order just to get the answers, but have no real idea of why the answers are what they are.”

It’s a brilliant term, and it’s not just a metaphor. Much like technical debt in software, when quick fixes now create major rework later, Cognitive Debt builds when we take intellectual shortcuts, trusting tools or systems without understanding them.

Why does this matter?

Because we’re entering an age where these shortcuts are everywhere. AI tools can deliver polished results with frightening speed, but without scrutiny, those results can be misleading, empty, or outright wrong. When organizations or individuals rely too heavily on AI without asking, “How do I know this is true?” or “What is the thinking behind this?”, they’re accruing cognitive debt they’ll eventually have to repay: often in the form of lost trust, confusion, or reputational damage.

“Cognitive Debt will increasingly be accrued globally, with low-specificity, and unclear accountability.”

This is a curiosity problem. When we stop being curious about why something works, about what a result really means, or about how it came to be, we put ourselves at risk of being misled by systems that are only ever as good as the thinking behind them.

The woman who fooled the President

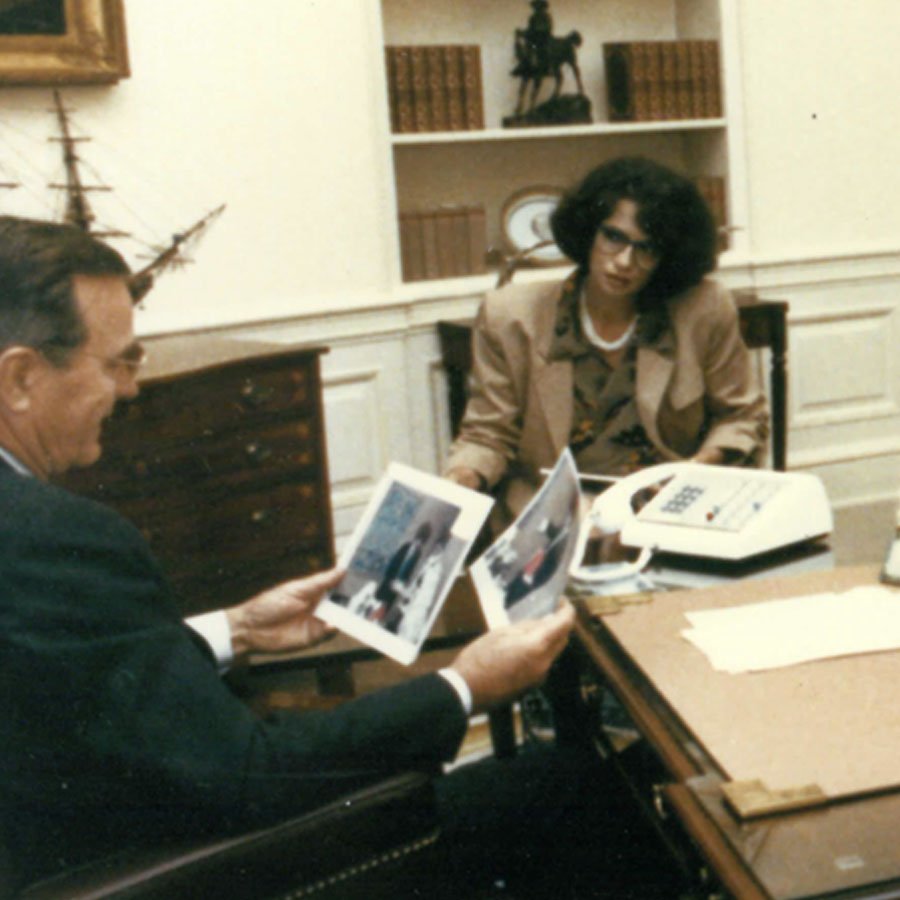

In 1990, a woman walked into the Oval Office to brief President George H. W. Bush on CIA operations. Her name was Jonna Mendez, and she was the CIA’s Chief of Disguise.

At the end of the meeting, she asked the President: “Would you like me to take off my disguise now?”

Before he could respond, she peeled off her face. Literally.

She had been wearing a hyper-realistic silicone mask the entire time. The President had no idea. None of his advisors did either. They hadn’t noticed, because they weren’t looking. They didn’t expect disguise, so they didn’t detect it.

When we don’t expect it, we don’t pay attention

That’s what stayed with me. Not just the spycraft or the technology, but this deeper, almost uncomfortable truth:

- We miss what we don’t expect.

- We overlook what doesn’t fit our mental map.

- We think we’re observant… but mostly, we notice what confirms what we already believe.

Finishing a book and seeing new perspectives

Last week I finally finished reading Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes by Tamim Ansary. (Yes, I wrote about it earlier)

The book tells the story of the world not from the familiar European perspective, but from within the Islamic tradition. Its story begins in a different place, follows a different rhythm, and sees a different center of gravity. And what becomes clear, page after page, is that we are not all looking at the same world. We are looking from different places, along different storylines.

We are all living inside a story. But not always the same one.

History isn't a timeline. It's a storyline.

This was the first major shift for me. We’re taught history as if it’s a straight line: dates, conquests, revolutions, all pointing toward modernity. But Ansary reveals that this linear view is only one version of events. In the Islamic world’s own narrative, history follows its own arc, guided by its own questions, values, and turning points.

Europe appears, but not as the main character. The Islamic world had its own momentum, its own periods of discovery and crisis, and its own sense of destiny. Shaped not by Europe, but by its own internal rhythms.

Where you stand shapes what you see

The second insight that stayed with me is how radically different the world looks depending on your vantage point. A familiar example becomes strange when told from another angle. The Crusades, for instance, are often remembered in the West as a religious battle between Islam and Christianity. In the Islamic telling, they were a brutal invasion. A sudden, barbaric attack on the edges of a thriving civilization. The same event. A completely different emotional truth.

This isn’t just about history. It’s about how we move through the present. Curiosity begins when we stop assuming that our view is the only view, or even the central one.

Civilizations don’t always clash. Sometimes they misread.

The third shift in perspective came from the idea that many global conflicts haven’t been about direct opposition, but deep misunderstanding. Civilizations move at different speeds. They are animated by different questions. The mistake is not always hostility. Sometimes it is the absence of curiosity.

One moment in the book captures this perfectly. Ansary describes how the steam engine appeared in the Islamic world and in China long before it powered the Industrial Revolution in Europe. But it didn’t cause upheaval in those places. Not because it was rejected or dismissed, but because it wasn’t needed.

These societies had abundant human labor and highly structured systems of governance and commerce. They could already do what they needed to do. Mechanisation didn’t solve a problem they were facing. The same technology landed in a different context and caused no revolution.

Progress is not just about what is invented. It’s about what is needed, what is allowed, and what is imagined to be possible.

Curiosity is about shifting your angle

Reading this book didn’t give me clearer answers. It gave me better questions.

Like:

- What stories have I accepted without knowing it?

- What might the world look like from a point of view I’ve never tried to understand?

- How many so-called facts are really just someone else’s framing?

We often think of curiosity as a hunger for more knowledge. But sometimes it’s not about learning more. It’s about standing somewhere else. Seeing through someone else's lens. Listening to someone else’s version of the story.

That’s what Destiny Disrupted offered me. Not a different set of facts. A different place to begin.