TWIL #53: From Prison Food to Ancient Bread

Every Sunday, I write down a few things that caught my attention that week: details I tripped over, ideas that lingered, questions I needed to understand by putting them into words. This isn’t about being right or complete. It’s about noticing, wondering, and thinking on the page.

Thanks for reading. I hope something here sparks.

Lobster: when abundance becomes embarrassment

I was watching The Diplomat (season 3, absolutely love it!) when someone casually mentioned that lobster used to be poor man’s food. What!?

In 17th- and 18th-century North America, lobster wasn’t rare.

It was inconveniently plentiful.

So plentiful it piled up on beaches after storms.

So plentiful it was ground into fertilizer.

So plentiful it was fed to servants, prisoners, and apprentices because it was the cheapest protein available.

Some indentured servants even negotiated contracts limiting how often they could be forced to eat it. Too much lobster was considered inhumane.

Not because it tasted bad. But because abundance strips things of meaning.

Lobster didn’t change its fate in a kitchen.

It changed it on a map.

For a long time, it lived too close to the shore. Too close to the people who caught it. Too close to abundance. When something washes up at your feet, it cannot feel special. It is just there.

Then the world stretched.

Ice slowed time.

Rails collapsed distance.

Cities grew far from the sea.

Suddenly, lobster had to travel. It had to survive the journey. It had to arrive intact. Many didn’t. And what arrives rarely begins to feel valuable.

Far inland, lobster became a rumor before it became a meal. Something you ordered, not gathered. Something that came with a story.

Scarcity did the first quiet rewrite.

Distance added mystery.

Price finished the sentence.

Nothing about the lobster changed.

But the world rearranged itself around it.

So what else feels ordinary today—only because it’s still washing up at our feet?

Why the Netherlands has so few castles

I watched the video above on why the Netherlands has so few castles compared to its neighbors. The insight that stuck was simple: castles are not just buildings. They are choices, made visible in stone.

So why do we, the Dutch, have so few?

Castles grow where land needs defending. Germany’s hills and valleys encouraged fortification. Belgium sat on a European fault line and built walls.

The Netherlands was different.

Flat land offered few natural defenses, and castles were easy to bypass. Our location also mattered. The Netherlands sat slightly off Europe’s main land routes, making it less attractive for large, land-based wars. Conflict still came, but differently, at sea and through trade.

More importantly, power here was never anchored to a castle. It lived in cities, ports, councils, and trade networks.

Commerce mattered more than territory.

Ships more than stone.

Contracts more than inherited walls.

Merchant capitalism does not need castles. It needs movement and trust.

The Dutch built a republic where power moved.

Bread, five ways

While researching how lobster went from punishment food to luxury, I kept running into the same idea: food doesn’t change nearly as much as meaning does. Scarcity, distance, and context rewrite how we see what we eat.

At the same time, I’m planning to bake fresh bread this weekend. Nothing fancy. Just flour, water, time. And it struck me how strange that feels now. Bread was once the foundation of life. Today it’s a lifestyle choice.

So I started exploring the history of bread, not as a recipe, but as a mirror.

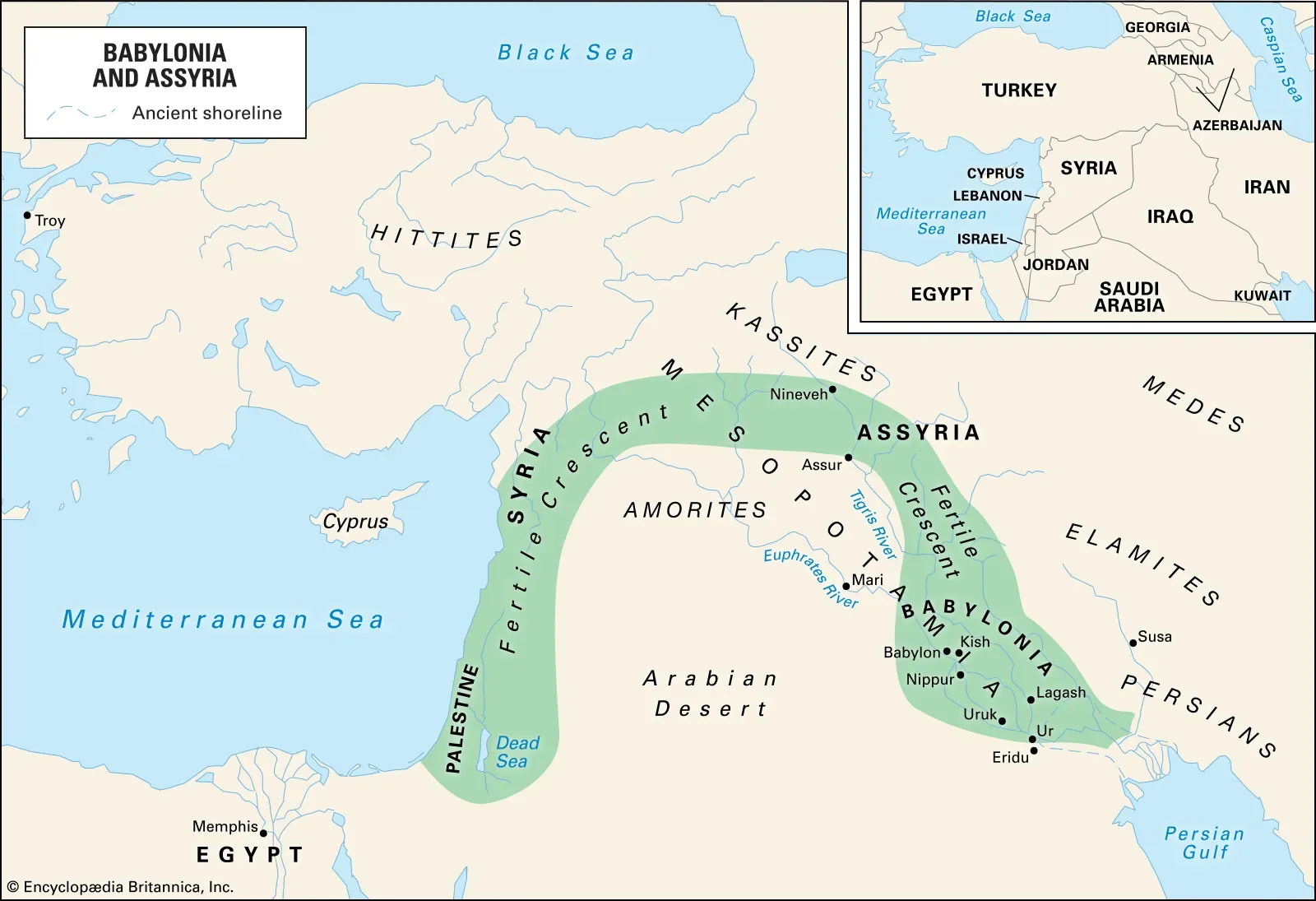

Bread as settlement.

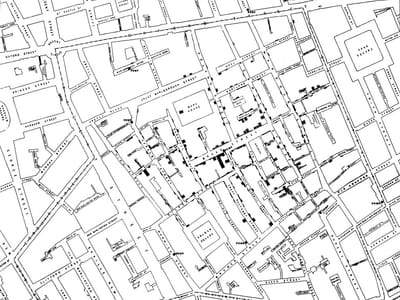

The Fertile Crescent, around 10,000 BCE.

Bread begins before cities, but it is what makes cities possible. Grinding grain takes time. Baking takes patience. Storing grain requires staying in one place.

Once people began making bread, they stopped moving. Bread quietly anchored humans to land. It was not cuisine yet. It was commitment.

Making bread assumes tomorrow. It turns wandering into waiting, calories into surplus, surplus into planning. With bread came storage, schedules, cooperation, and the idea that the future could be shaped rather than chased.

Walls, markets, and laws came later. Bread came first.

That is why bread feels larger than food. It is one of the earliest technologies of staying, a small daily act that made something much bigger possible. And maybe that is why baking bread still feels different. Even now, it carries the memory of the moment we chose to build a world instead of following one.

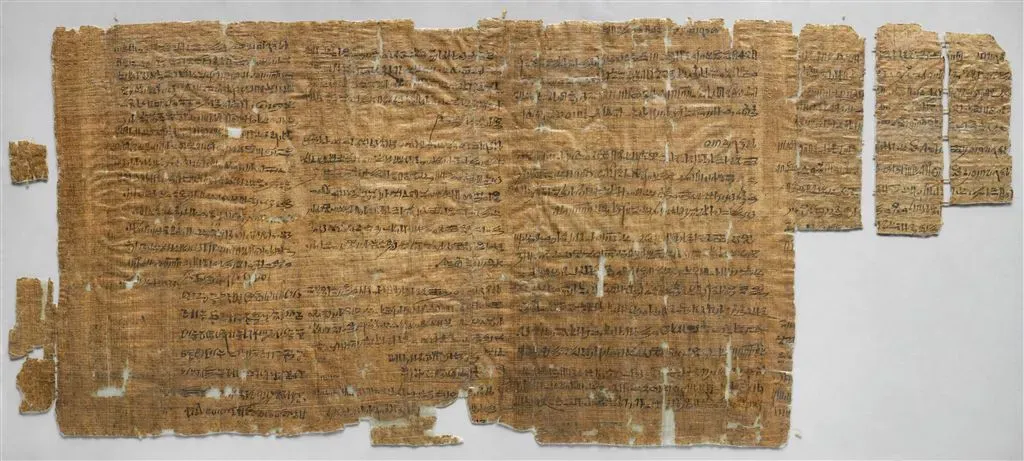

Bread as currency.

Ancient Egypt.

In Egypt, bread was pay. Workers were compensated in loaves. Temples tracked bread rations. The same fermented dough produced both bread and beer. Bread was placed in tombs to feed the dead in the afterlife. Bread was not a symbol of life. It was life, counted and distributed.

Take, for example, the Turin Strike Papyrus, written around 1152 BCE during the reign of Ramesses III. The document records how royal tomb builders in Deir el-Medina stopped working when their grain rations failed to arrive.

There is no debate about wages or ideology. The complaint is simple and direct: they were hungry. Officials negotiated by redistributing grain, and work resumed only once bread was secured. The papyrus makes the system unmistakable. In ancient Egypt, food was wages, administration ran on rations, and power was exercised through the reliable delivery of bread.

Bread as power.

Ancient Rome.

Rome understood a simple rule. Hungry people do not stay calm.

As the city grew, bread stopped being a household matter and became a matter of state. The Cura annonae, Rome’s grain distribution system, fed hundreds of thousands of citizens. Ships crossed the Mediterranean not for luxury, but for wheat. When grain was delayed, unrest followed quickly. Bread shortages did not cause inconvenience. They caused riots.

Roman thinkers noticed what this reliance on bread was doing to civic life. Cicero, writing in the final years of the Republic, still believed a state depended on active and responsible citizens. Bread was necessary, but it was never meant to replace participation.

A century later, Juvenal described what replaced that belief. Writing under the Empire, when ordinary citizens no longer held real political power, he observed that the public no longer demanded a voice in governance. The people who once granted offices, commands, and legions now desired only two things: panem et circenses. Bread and games.

Juvenal was not praising popular contentment. He was pointing to a trade that had already been made. Political participation had been exchanged for provision and distraction. Power no longer needed to persuade or involve. It only needed to feed and entertain.

“Bread and games” was not a slogan.

It was a diagnosis of how civic life had quietly slipped away.

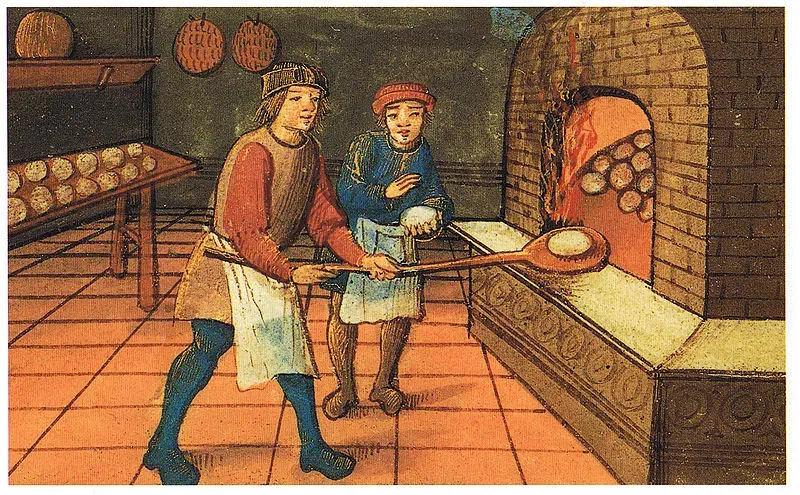

Bread as hierarchy.

Medieval Europe.

Everyone ate bread, but not the same bread. White wheat bread signaled wealth. Dark rye and barley bread signaled poverty. What you ate revealed who you were. Lords owned communal ovens, and peasants paid to use them. Baking was regulated, timed, and taxed.

Even stale bread had a role. It became plates, then food for the poor.

But bread also carried spiritual weight. It appeared in prayers, fasts, and rituals. In Christian Europe, bread became body, sacrifice, and promise. To waste bread was sinful. To break it was communal. To bless it was to acknowledge dependence on forces beyond human control.

Bread structured daily routine, reinforced hierarchy, and anchored belief. It told you when to work, where to stand, and what to thank God for.

Bread was never just nourishment.

It was a social and spiritual map.

Bread as suspicion.

The industrial world to now.

Industrial milling made bread cheap, white, and shelf stable. Nutrients disappeared. Effort vanished. Bread became invisible. Now we negotiate it. Carbs. Gluten. Cheat days. At the same time, we romanticize it again through sourdough, heritage grains, and long fermentation. Bread returns as ritual because it no longer has to be survival.

Bread changes meaning as our relationship to hunger changes.

When hunger is near, bread is sacred.

When hunger is managed, bread is political.

When hunger is distant, bread is questioned.