TWIL #20: From Eggonomics to New Bodies

Every Sunday, I share a few of my learnings, reflections, and curiosities from the week. Things I stumbled upon, things I questioned, things that made me look twice. It’s not about being right or complete… it’s about noticing, wondering, and learning out loud.

Thanks for reading. I hope it sparks something for you too.

The impact of eggs on a presidency

This week I was listening to a podcast about the USA (BNR’s Amerika Podcast). In it, they spoke about the popularity of the president and what it depended on. Not the war. Not the big themes in the world. Not Ukraine. Not inflation reports or international diplomacy.

What mattered more, the host said, was the price of eggs.

I had heard this before, but this time it triggered me to dive deeper.

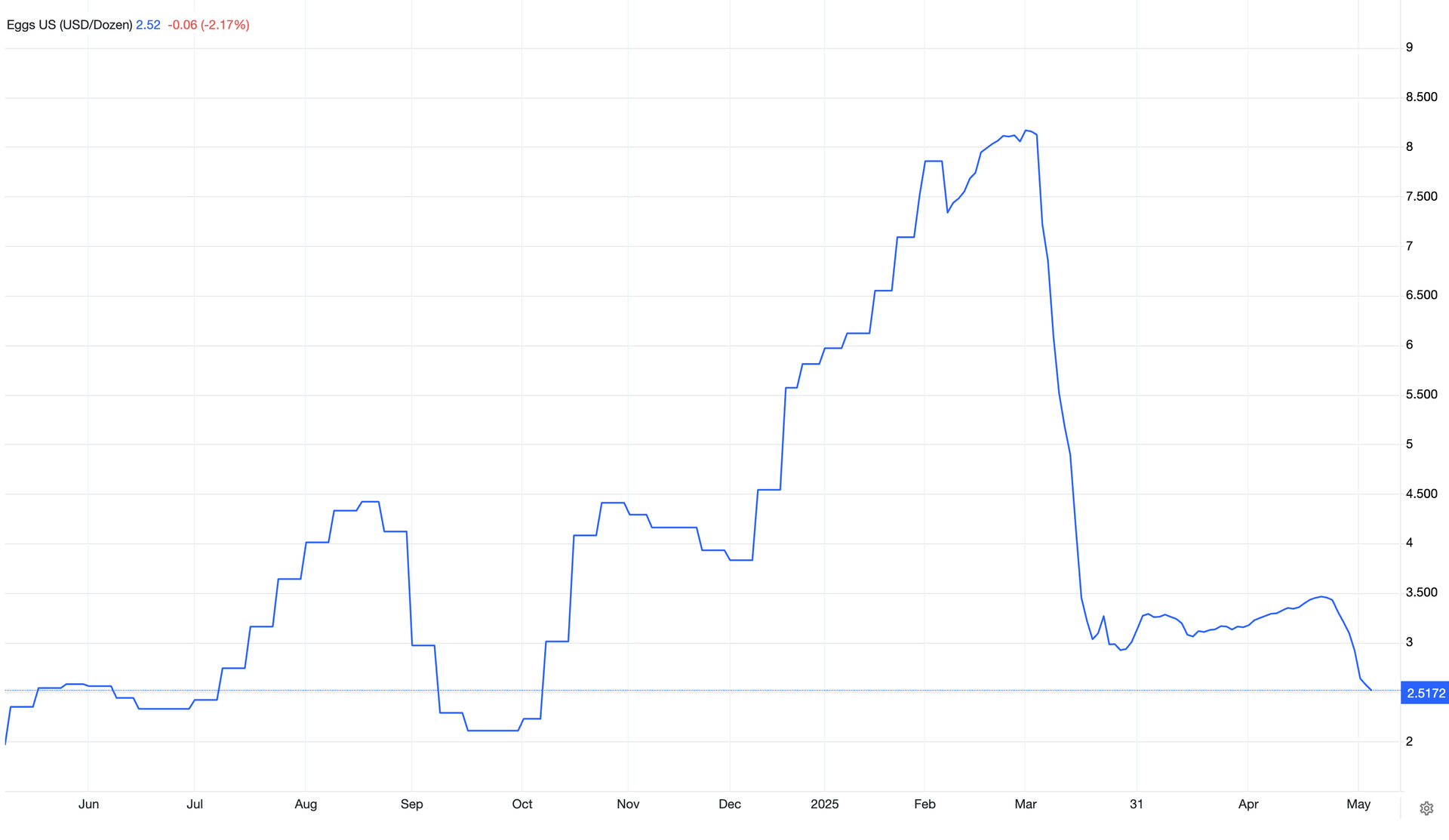

People do not track the economy in graphs or trends. They do not study price indices or analyze year-on-year data. Most people watch the world through what they pay at the store. And eggs are a perfect reference.

They are bought frequently. They are simple, familiar, and essential. You don’t need to be an economist to know when something feels wrong. When eggs jump from two dollars to six, it does not feel like economics. It feels like something in everyday life has quietly broken.

That small shift in perception is powerful. When prices rise in a way that touches people directly, it shakes trust in the system. If leaders or institutions say “everything is fine” while the grocery bill tells another story, people start believing something is not right. For Trump it might be more important to keep the price of eggs low instead of piece in the Ukraine and the Middle East.

But I kept digging. Are there more of these signals, like the price of eggs, that quietly reflect how people are really doing? Small things that seem trivial but actually hold meaning?

Yes. There are. (Of course… everything you can imagine exists)

A few surprisingly powerful economic signals

- The Big Mac Index — This global comparison tool was created by The Economist. It measures how much a Big Mac costs in different countries to estimate real purchasing power. Because the Big Mac uses standard ingredients across nations, it creates a baseline for currency value. It is not perfect, but it gives a glimpse into how far money goes, country to country.

- The Lipstick Index — This idea emerged in the early 2000s. When times are tough, people often stop buying large luxury items. But small indulgences remain. Lipstick sales often rise during downturns because people still want to feel good without spending much. It is a subtle signal of financial pressure and emotional adaptation.

- The Men’s Underwear Index — The thinking goes like this: when men are cutting back on spending, they delay buying underwear because it is not visible. So a drop in underwear sales can suggest that households are under more financial strain than official data might show.

These small, ordinary signals may seem too simple to matter, but they reveal something deeper: how people actually feel about their place in the economy. And often, those feelings shape political decisions more than any policy or speech ever could.

What other quiet signals are hiding in plain sight, already shaping the world before we’ve learned to name them?

New cells, old thoughts

This week I learned that your stomach gets a new lining every few days. It has to. The acid inside is strong enough to dissolve bone, so if your body didn’t rebuild that layer constantly, your stomach would digest itself. That tiny fact made me pause. While we go about our day, there is a silent construction crew inside us, rebuilding, repairing, and keeping us from falling apart without us even noticing.

Most of your body works like that. Skin replaces itself every few weeks. Blood renews every few months. Even your liver turns over within a year. Scientists say much of your body is replaced every 7 to 10 years. But here is the strange part: your thoughts do not renew. The cells in parts of your brain can last a lifetime. Your memories, your personality, your inner voice: they stay. So while your body quietly becomes new, your mind carries a continuous thread. It makes you wonder: if we are always changing, yet somehow always ourselves, what part of us is doing the staying?

The Jevons Paradox: When efficiency backfires

My wife was talking about a talk she went to this week and suddenly said: “Have you heard of the Jevons Paradox?”

At first I thought she said “Jefron Paradox,” which sounded like a sci-fi character. But no, this was real and surprisingly relevant.

The Jevons Paradox comes from 19th-century economist William Stanley Jevons. He noticed that as steam engines became more efficient, using less coal per unit of power, coal use didn’t drop. It rose.

Why? Because efficiency made steam cheaper and more useful, so it spread faster.

That’s the paradox: greater efficiency can lead to more consumption, not less.

And once you see it, it’s everywhere:

- Fuel-efficient cars — Better mileage should reduce fuel use. But cheaper driving often leads to more driving or buying bigger cars.

- LED lighting — LEDs cut energy use per bulb. But now we light everything: buildings, pathways, advertisements. The total energy use doesn’t always fall.

- Digital photography — Film used to limit how many photos we took. Now, with no cost per shot, we take thousands and struggle to manage the overload.

- Time-saving tech — Tools meant to save time often increase workload. Email, automation, and smart apps create more capacity, but also more expectations.

The Jevons Paradox is not about failure. It is about feedback loops. We assume that efficiency means reduction, but it often changes behavior, encouraging more of what we were trying to manage.

So here’s the question I’m left with: Where in out lives has efficiency made things easier, but also heavier?

And what happens if we stop chasing faster and ask whether less might actually be enough?