TWIL #21: From Conversations to Perspectives

Every Sunday, I share a few of my learnings, reflections, and curiosities from the week. Things I stumbled upon, things I questioned, things that made me look twice. It’s not about being right or complete… it’s about noticing, wondering, and learning out loud.

Thanks for reading. I hope it sparks something for you too.

Spinning into the unknown

This week I had a conversation with Antonio Iturra from The SLOW Creative. A real conversation, the kind that doesn’t follow a set agenda or chase a clear outcome. The kind that meanders.

At one point, Antonio said something that stuck:

“The word conversation comes from the idea of spinning around.”

That phrase set something spinning in me too. I looked it up.

It turns out that conversation comes from the Latin conversari, meaning “to turn about with,” or more poetically, “to live with.” It implies movement, not in a straight line, but in orbit. Not a march toward a known destination, but a dance around an idea, a feeling, a moment.

And yet, how many meetings, calls, and catch-ups today begin with:

“What are we trying to get out of this?”

“Where is this going?”

“What’s the agenda?”

We’re addicted to clarity. To conclusions. To mapping the road before we step onto it.

But what if the most meaningful things arise not in the answers, but in the spin?

In not knowing where it leads.

In entering a space with curiosity instead of control.

In trusting that circling something together might just reveal more than chasing it ever could.

This week I learned (again) that a real conversation doesn’t always go somewhere.

Sometimes it goes around, and that’s where the magic is.

And here’s something curious: in physics, spin is not just movement. It’s a fundamental property of matter, something that defines the very identity of particles. So perhaps spinning around an idea isn’t aimless after all. It’s essential.

A small experiment, if you're curious:

- Ask someone: “What’s something you’ve been thinking about a lot lately?”

- Start a conversation with a stranger, even briefly, with no goal other than to notice where it goes.

- Resist the urge to steer. Just spin together.

You might not get anywhere. But you might just end up somewhere you never expected to be.

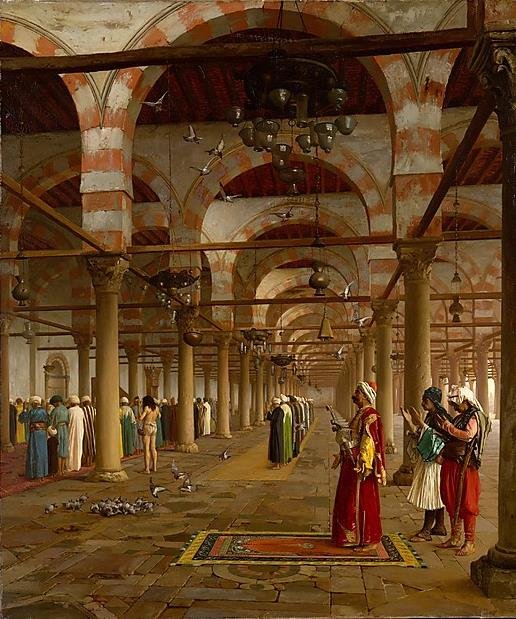

Gérôme’s Lens

This week I learned about Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), the painter. I came across his work almost by accident, via a post of The Culturist. It stopped me mid-scroll.

What struck me wasn’t just the subject, but the point of view.

His work feels cinematic, like a still from a film that hadn’t been invented yet.

Gérôme’s paintings don’t just show events. They observe them. From odd angles, with deliberate distance, or eerie intimacy. It’s not always what he shows, it’s where he places you.

But the deeper I looked, the more I realized the real story is not just the work.

It’s how he got there.

Gérôme started conventionally, with classical training, mythological themes, and polished technique. His early work, like The Cock Fight (1846), showed promise. It won prizes. It followed the rules. But even then, there was something else, a sense of tension, a curiosity for what happens just after the main event.

Then he started to travel.

He went beyond Europe: to Egypt, Turkey, Syria, Algeria. He didn’t go for a weekend. He went to see. He sketched, studied, and collected architecture, fabrics, weapons, habits. Not to romanticize, but to reconstruct. To understand.

The painter became something like a director. He staged history with near-obsessive accuracy, but chose to frame it with detachment, subtlety, and distance. His brush wasn’t chasing emotion. It was setting a scene and letting you walk into it.

In Prayer in the Mosque (1871), for instance, there’s no drama. Just light, architecture, stillness. The hum of real life.

In Pollice verso (1872), you’re in the Colosseum, but not in control. You’re witnessing something terrible. Something ordinary, in that time.

And then there’s Rider and His Steed in the Desert. A lone figure, motionless, sits atop his horse in the emptiness of sand and silence. There is no narrative, no drama… just presence. Gérôme positions us slightly behind and to the side, as if we’ve paused on our own journey and are watching this one unfold in parallel. The desert stretches endlessly around them. Nothing moves. And yet, something in the stillness speaks. We are not part of the scene: we are witnessing it, quietly, from a respectful distance.

This is what Gérôme does. He doesn’t just paint scenes. He chooses how we see them. And that, I think, is what makes his work feel strangely modern.

He embraced photography. He experimented with depth, cropping, and perspective. He made paintings that behave like film, long before film existed.

This week I learned that Jean-Léon Gérôme was more than a master painter. He was a traveller, an observer, a technician of point of view. His work invites us to step out of the center of the story and into someone else’s world, even for a moment.

And maybe that’s what curiosity really is. Not just looking.

But changing where you look from.

My learnings from this:

- Where you stand changes what you see. The most revealing perspective is often just a few steps to the side.

- Curiosity isn’t loud. It’s quiet attention, deep observation, and the willingness to witness without rushing to interpret.

- Mastery comes from movement. Gérôme’s brilliance didn’t come from staying in the studio. It came from going, seeing, collecting, and returning with questions.

Same Song, Different Soul

This week I’ve been listening to Mr. Bojangles again.

Not just once… but in many versions, by different voices.

I’ve always been fascinated by how this one song changes depending on who sings it. Same melody. Same story. But the emotion shifts. Sometimes it aches. Sometimes it smiles. Sometimes it feels like a confession. Other times, a tribute.

Jerry Jeff Walker wrote it after a chance meeting with a street performer in a New Orleans jail. Just a brief encounter. A man who danced when he remembered. And cried when he didn’t.

Since then, Mr. Bojangles has been sung by:

- Jerry Jeff Walker, with a kind of weary affection, like someone still processing the moment

- The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, in a version that feels like sitting around a campfire with ghosts

- Sammy Davis Jr., with precision and reverence, as if telling his own story in disguise

- Nina Simone, who strips the song bare. Her version is slow, hesitant, intimate, as if she’s letting grief surface in real time

- John Denver, whose voice I love, but here it’s too sweet. The performance smooths over the ache. The emotion never quite lands

- Robbie Williams, polished and theatrical. He mimics Sammy Davis Jr., but never lets us hear his voice in the telling. The performance is technically perfect, but emotionally sealed

The same song.

But completely different souls.

And that’s what strikes me: the emotion isn’t in the words. It’s in the telling.

Like all stories, Mr. Bojangles lives in the space between the lines.

In the pauses, the breath, the tempo.

In the choice to lean into a phrase. Or to play it safe.

👋 See you next week.