TWIL #22: From Tough Creatures to Up Close Maps

Every Sunday, I share a few of my learnings, reflections, and curiosities from the week. Things I stumbled upon, things I questioned, things that made me look twice. It’s not about being right or complete… it’s about noticing, wondering, and learning out loud.

Thanks for reading. I hope it sparks something for you too.

The toughest creature on Earth

They mentioned it on the radio this week: the tardigrade. I’d heard of it before, but this time something about the way it was said caught me. I went looking again, curious.

What I found didn’t feel like reading about a micro-animal. It felt like uncovering a quiet miracle.

Tardigrades are smaller than a millimetre, soft-bodied, eight-legged. They live in moss, lichen, roof gutters. But they can survive boiling, freezing, radiation… even outer space.

In 2007, scientists launched them into open space. No suit, no shield. Just vacuum and solar radiation. They survived. Some even reproduced after returning.

That fact alone rewrites what we think life can endure. Tardigrades do this by entering cryptobiosis, a kind of suspended animation. They dry out, shut everything down, and wait. When conditions improve, they rehydrate and carry on.

And that made me wonder:

If they can survive space, could they travel through it?

It’s not just science fiction. The idea that life might spread between planets, is a serious theory. It is called: panspermia, and it suggests something bold: that life spreads through the universe like seeds on the wind. That planets don’t birth life in isolation, but receive it. That biology might be far more mobile than we’ve ever imagined.

What!? Yes, definitely something to dive into.. so I did:

So what exactly is panspermia?

The word comes from Greek: pan (all) and sperma (seed). It’s the idea that the building blocks of life, or even life itself, might travel from one celestial body to another, hitching rides on comets, asteroids, meteorites, dust clouds, or even spacecraft.

There are a few versions of the theory:

1. Lithopanspermia

This is the most studied version. It suggests that life can be ejected from a planet (by an asteroid impact, for example), survive the journey through space inside rocks, and land on another planet. Earth has received tons of meteorites from Mars. Some even contain possible fossil-like structures.

Could early life on Mars have come to Earth this way? Or vice versa?

2. Radiopanspermia

Proposed by 19th-century scientists like Svante Arrhenius, this version suggests that microscopic life or organic particles could float freely through space, pushed by light pressure. Today we know that space is harsher than Arrhenius imagined, but some hardy microbes (and, yes, tardigrades) have shown surprising resistance to radiation and vacuum.

3. Directed panspermia

A more speculative and provocative idea: what if life was deliberately seeded on Earth (or elsewhere) by an advanced civilization? This was seriously proposed by Francis Crick, co-discoverer of DNA. He didn’t necessarily believe it happened: he simply asked whether it could explain the complexity of life. (A What if… scenario)

In all versions, the core idea is the same: life is not stuck. It moves. It spreads.

Which raises an unsettling but beautiful question (start mystical music intro now): What if the tardigrades didn’t come from here?

What if the moss in your garden holds the last remnants of something much older, much further-travelled than we are?

It’s not provable. But it is possible.

That’s what I love about this creature. It lives in silence, but its existence asks bold questions. It challenges our ideas of fragility, time, and even origin.

The map that shows America up close

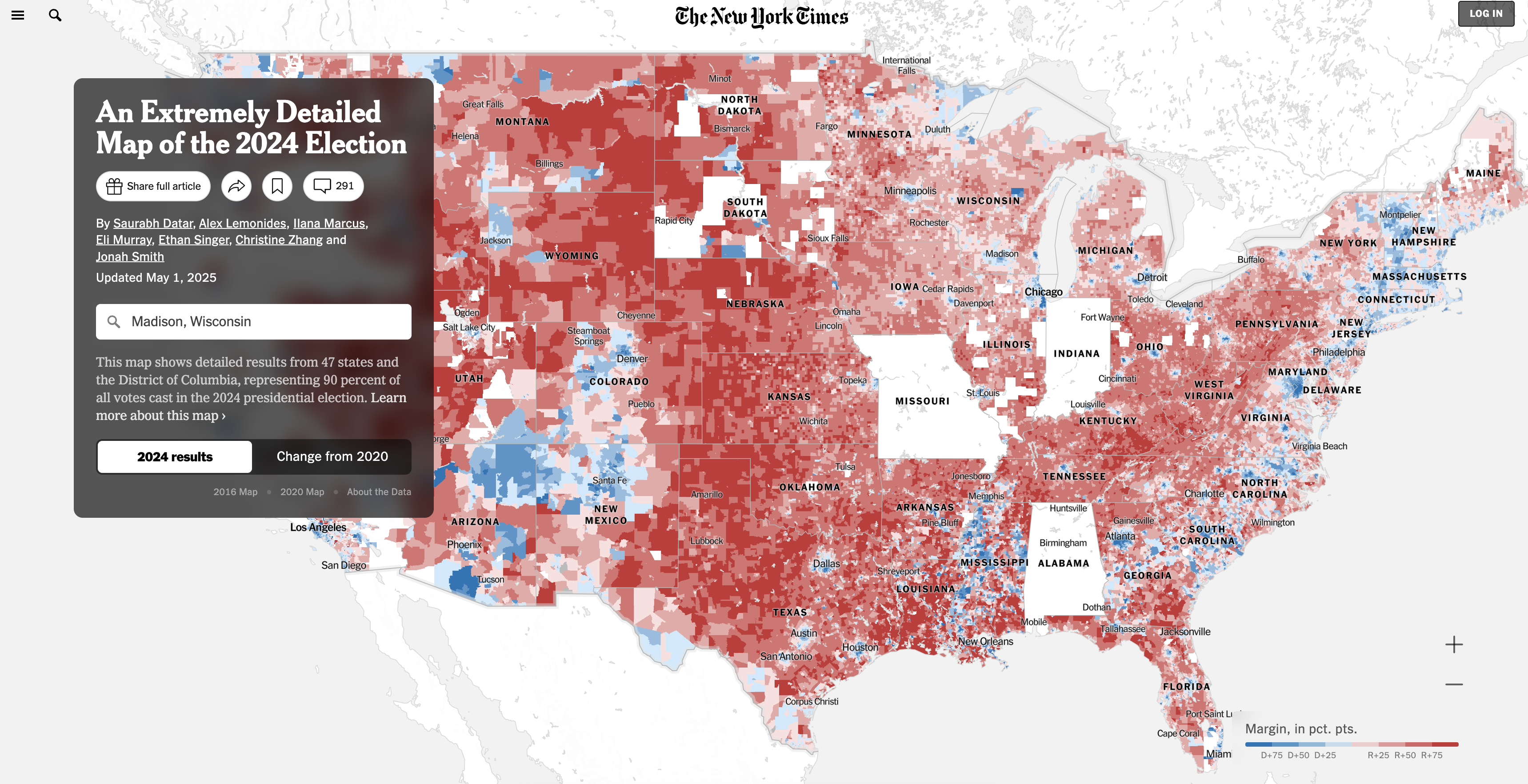

I love maps… and even though this one is from 2024, I have been scrolling around for some time now. This is The New York Times 2024 Election Map (Precinct-Level)

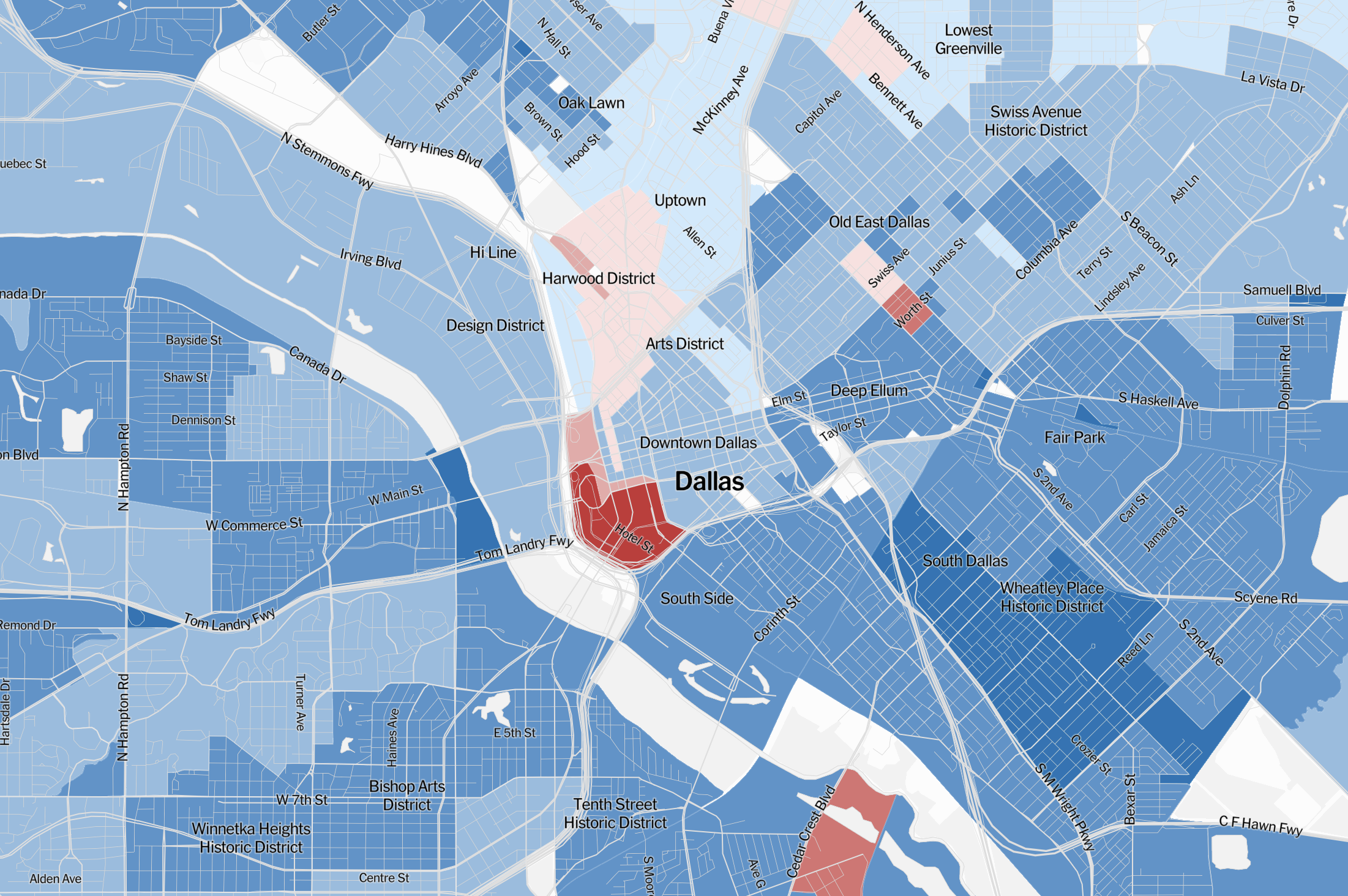

It’s not just a political map. It’s a portrait of the country at the level of neighborhoods and intersections. When you zoom in, patterns appear that are easy to miss at the national scale.

Here are a few of the details that caught my attention:

- Cities are not just blue. Inside San Francisco, Miami, and Los Angeles, you’ll find red-leaning precincts tucked into overwhelmingly blue regions. Cities contain more contradiction than headlines suggest.

- College towns glow. Small places like Ithaca, Madison, and Boulder show strong voting patterns that sharply contrast with the rural areas around them. The presence of a university seems to change the whole shape of the map.

- Some precincts report just one vote. Even in places like Los Angeles. It makes you wonder. Is it an artifact of how voting is counted, or a glimpse of someone voting where almost no one else did?

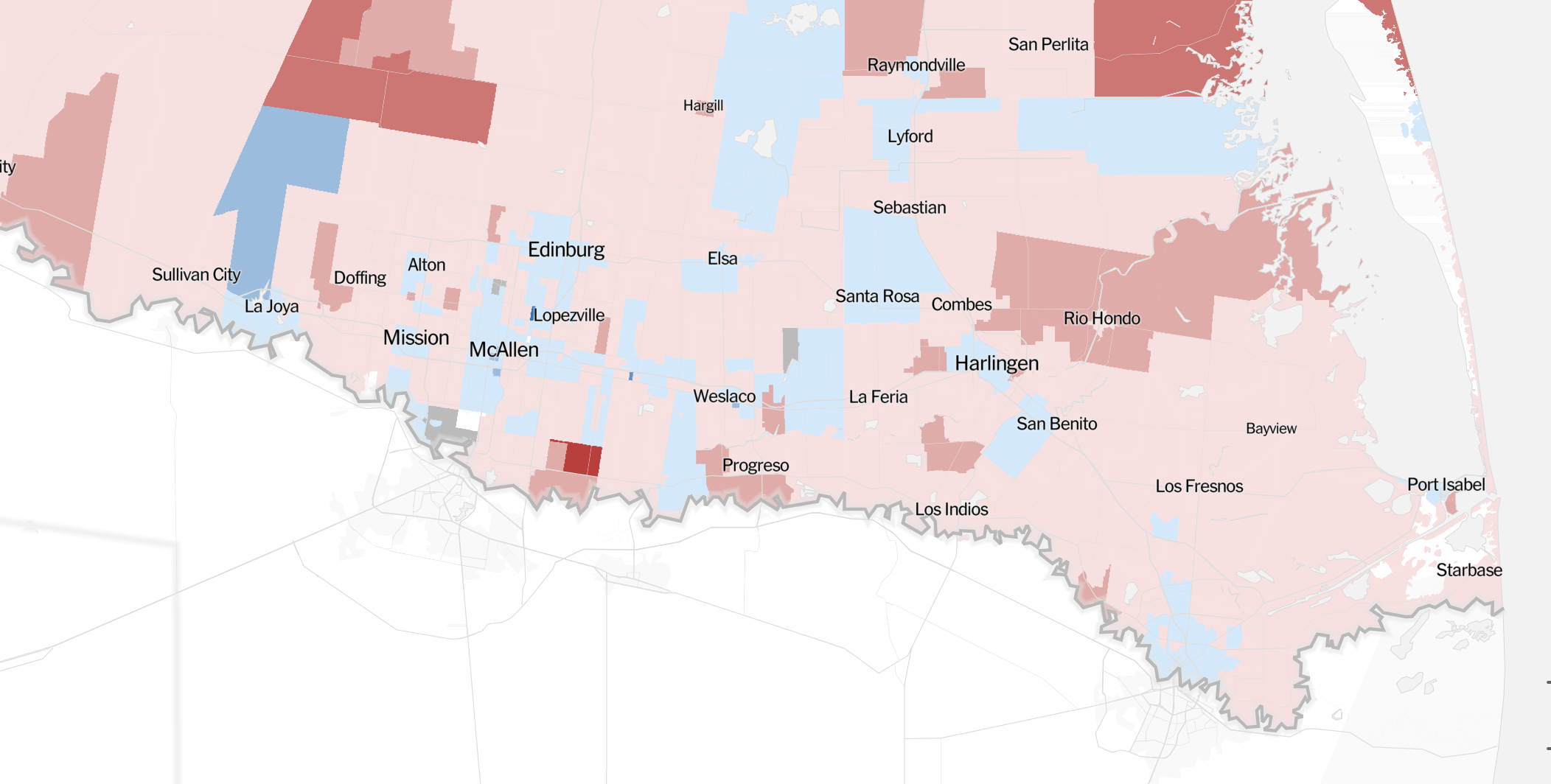

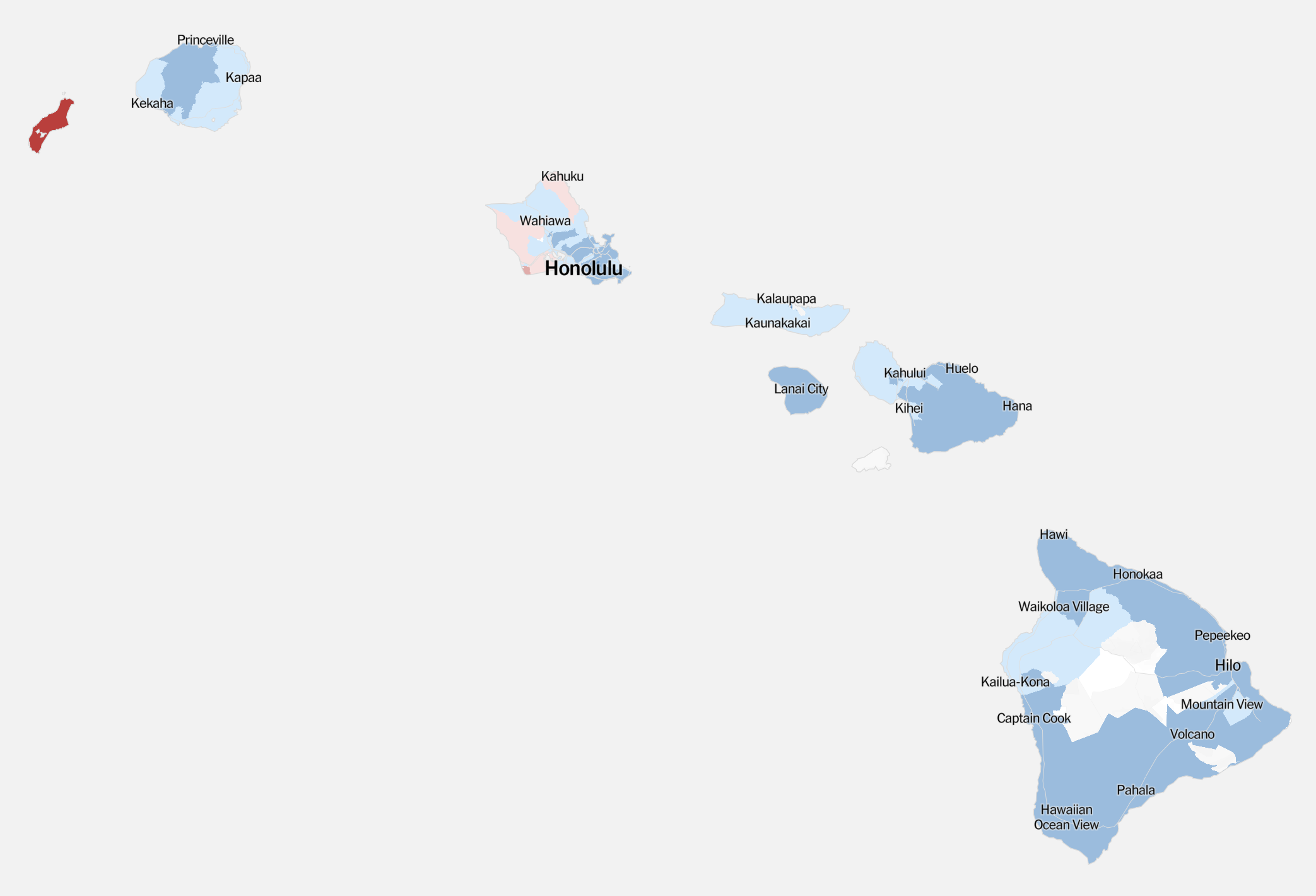

- Native lands and border towns draw their own lines. Their voting patterns don’t always follow national trends. They often reflect entirely different political conversations shaped by sovereignty, identity, and history.

This map rewards curiosity. The more you zoom in, the more the country stops being abstract. It becomes specific. Local. Human.

Let me know if you spot anything strange or beautiful in your own area.

The wild that almost wasn’t

I’m just finishing season four of Yellowstone on Netflix. In one scene, John Dutton tells a boy, “My grandfather saved the bison.”

That line stuck with me.

So I looked it up.

By the late 1800s, bison (once roaming 30 to 60 million strong across North America) had been reduced to a few hundred animals. In Yellowstone, just 23 bison survived, hidden in the remote Pelican Valley, one of the most isolated parts of the park.

The destruction wasn’t an accident.

The U.S. Army and federal officials encouraged mass slaughter. Why? Because bison were central to Native American life: as food, shelter, clothing, and culture. No bison meant no resistance. It was ecological warfare disguised as economic expansion.

From that near-erasure, Yellowstone’s herd was painstakingly rebuilt. A few animals were added from private herds in the early 1900s, but most of today’s population descends from those original two dozen.

Today, around 5,000 bison roam Yellowstone. It’s the largest free-roaming, genetically intact bison herd in the U.S.

They look wild. They feel ancient.

But they are also descendants of crisis… living proof of what almost disappeared.