TWIL #27: From Fast Independence to Stones

Every Sunday, I share a few of my learnings, reflections, and curiosities from the week. Things I stumbled upon, things I questioned, things that made me look twice. It’s not about being right or complete… it’s about noticing, wondering, and learning out loud.

Thanks for reading. I hope it sparks something for you too.

Hello again, finally.

I’ve been in Slovenia for a week now, somewhere deep inside Triglav National Park. Last week I had bad Wi-Fi and no signal... so there was no newsletter. Just cold rivers, quiet mountains, and a surprising number of cows with bells (we were in Austria last week). But this time, no excuses. There’s simply too much to share.

Here are three stories from the last few days. One about nations. One about stones. One about horses fighting ships.

Slovenia: A quiet breakup

We’re in Slovenia now, walking along rivers, looking at the mountains, saying hi to all the nice people living here, and wondering how this little country did whien Yugoslavia collapsed.

Here’s what I found.

On 25 June 1991, Slovenia declared independence from Yugoslavia. It wasn’t just political theatre. It was backed by a referendum in which 88 percent of the population voted to leave. The Yugoslav army rolled in, but the fighting lasted only ten days. Around 70 people were killed. Not thousands. Seventy.

Then the army left. Slovenia was independent (well… three months later it was official…)

It’s one of the most peaceful exits from a collapsing federation in modern history. Why did it work here?

- No ethnic fault lines. Slovenia was almost entirely Slovene. No major ethnic divisions, unlike Bosnia or Croatia.

- Strong economy. It had the highest GDP per capita in Yugoslavia and was already trading with Western Europe.

- Good timing. Yugoslavia’s central government was weak, distracted, and already beginning to fragment.

- Short borders with Serbia. Unlike Croatia, Slovenia didn’t border Serbia directly, which meant fewer territorial disputes.

- Quick, clear action. The leadership was organised, the referendum was decisive, and they declared independence with little hesitation.

And then they got to work building a country. Quietly. Efficiently. Without fanfare.

Triglav National Park: Stones that shouldn’t be here

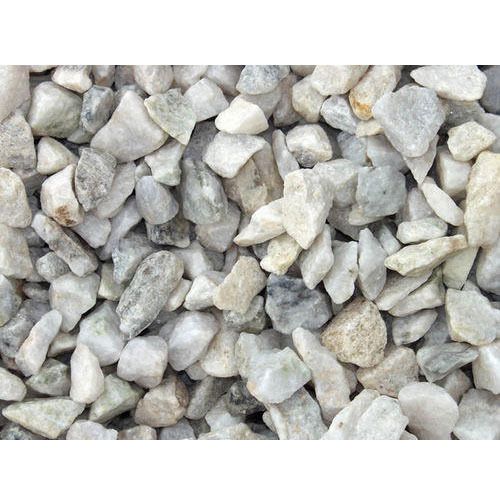

We’re camping right next to Triglav National Park. Most afternoons we wander down to the river and start building dam after dam, trying to outsmart the current with cold fingers and questionable engineering. And then we started noticing the stones.

Every holiday, we like to find one stone to bring home. A small reminder of where we were. Slovenia’s rivers, it turns out, make that decision difficult. There are too many worth remembering.

They are not just rocks. Stories.

Here’s what you can find in a riverbed here:

Limestone

This is the bedrock of Triglav. It formed hundreds of millions of years ago when this entire region lay beneath a warm, shallow sea. Tiny sea creatures died, their shells sank, and over time the pressure of layers turned all that calcium into stone.

What it looks like: pale grey to white, sometimes smooth, sometimes with fossil imprints… little spirals or ripples locked in time.

Where it came from: ancient seabeds, now uplifted into mountains.

Dolomite

Very similar to limestone, but slightly harder and less soluble. It also comes from marine sediment, but with magnesium mixed in. Over time, chemical changes in buried limestone turned it into dolomite.

What it looks like: sandy beige or light tan, often with a chalky feel and tiny pores.

Where it came from: the same ancient seas as limestone, altered deep underground over millions of years.

Quartz pebbles

You sometimes spot pebbles that look like pieces of ice — cloudy white, slightly translucent, or faintly sparkling. These are quartz, one of the most durable minerals on Earth. If you find a rougher version with grainy texture, it might be quartzite — sandstone that has been cooked under intense heat and pressure.

What it looks like: glassy, white or smoky, with sharp edges or rounded smoothness.

Where it came from: either high alpine rocks broken down by glaciers, or ancient sand compacted and transformed far below the surface.

Conglomerates and sandstone

Some stones are made of many stones. You can see little fragments stuck together like geological fruitcake. These are conglomerates — formed in ancient riverbeds, where rushing water deposited mixed gravel, later compressed into rock.

What it looks like: rounded pebbles trapped in a matrix, often reddish or brown. Sandstone is finer; layered, grainy, and worn.

Where it came from: long-lost rivers and floodplains, hardened into rock and now broken back down again.

Glacial Erratics

These are the outsiders… and my favorites. Huge boulders or small stones that don’t match anything around them. During the Ice Age, glaciers picked up rocks and carried them far from their origins. When the ice melted, it simply dropped them.

What it looks like: anything from greenish-grey granite to speckled black-and-white gneiss. Some are scarred from the journey, others worn smooth by meltwater.

Where it came from: far-off mountain peaks, dragged here by glaciers over tens of thousands of years.

We started bringing a few glacial rocks back to the camping. Not because they’re rare. But because they are so beautiful that we want to lock our holiday memories in them.

When horses captured ships

One last thing. Nothing to do with Slovenia, but it has to do with my home country. And I didn‘t know about it until yesterday.

In January 1795, the Dutch fleet was frozen into the sea near Den Helder. The ships couldn’t move. Ice held them fast.

So a French cavalry unit rode across the ice and captured the fleet. Horses versus ships. No cannon fire. No naval battle. Just frozen sails and sabres on horseback. The Dutch sailors surrendered.

It may be the only time in history that a navy was captured by cavalry. Which seems like a thing worth remembering.

I’ll write again soon, but not sure if that will be next week… we are moving towards a new camping again!