TWIL #40: From Bomb Statistics to Fading Images

Every Sunday, I share a few of my learnings, reflections, and curiosities from the week. Things I stumbled upon, things I questioned, things that made me look twice. It’s not about being right or complete… it’s about noticing, wondering, and learning out loud.

Thanks for reading. I hope it sparks something for you too.

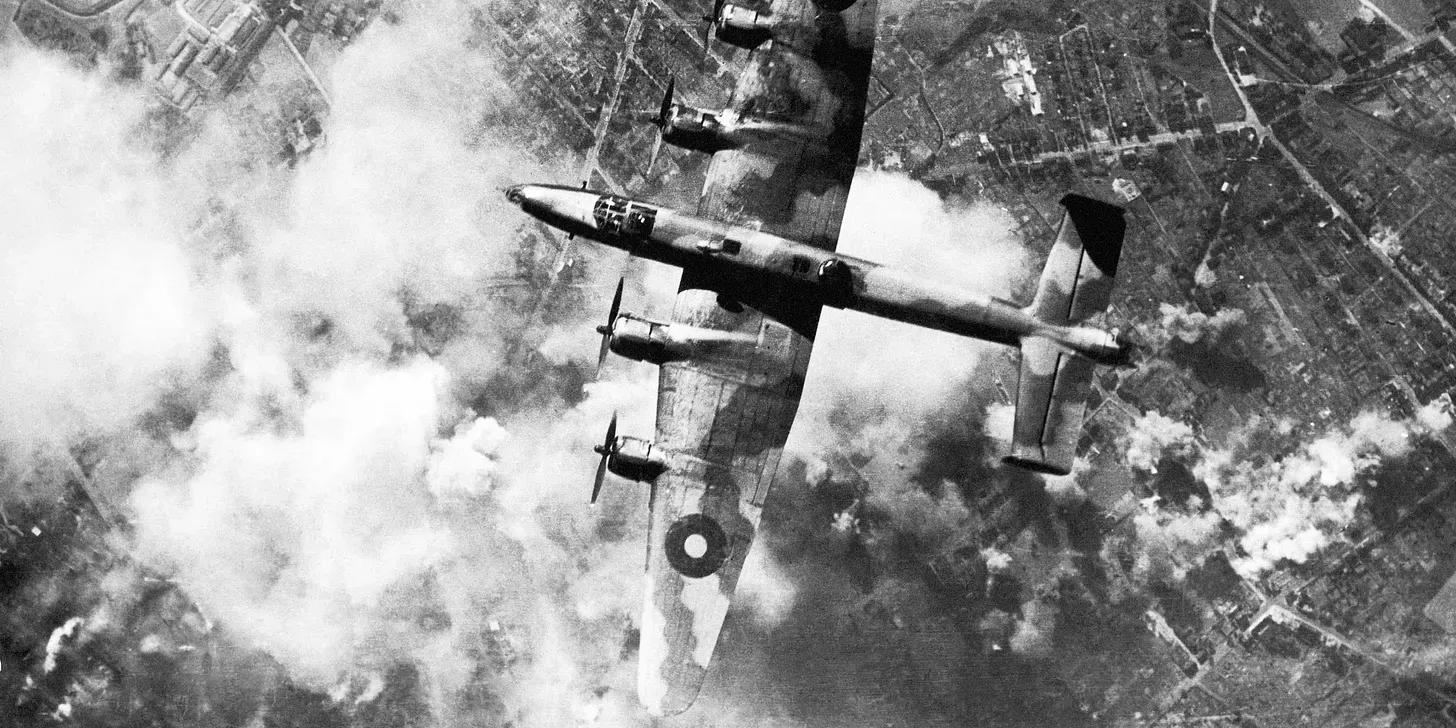

Six percent

I read somewhere that only six percent of bombs in World War II hit their intended targets, and I had to check if that could possibly be true.

It is.

Even the most “precise” bombing raids were wildly inaccurate. Most bombs missed by miles, and whole cities were destroyed chasing a single factory or bridge.

Once I started looking, I found more numbers from that war that are just as staggering:

- 50% of all Allied bomber crews were killed before completing their missions.

- 20% of all bombs dropped over Germany failed to explode.

- In some Pacific campaigns, more soldiers died from disease than from combat.

- 75% of German U-boat crews never returned home.

- On parts of the Eastern Front, a Soviet soldier’s average life expectancy after arriving at the front was less than 24 hours.

I started with one fact I didn’t believe and ended up reminded how enormous, messy, and human that war really was.

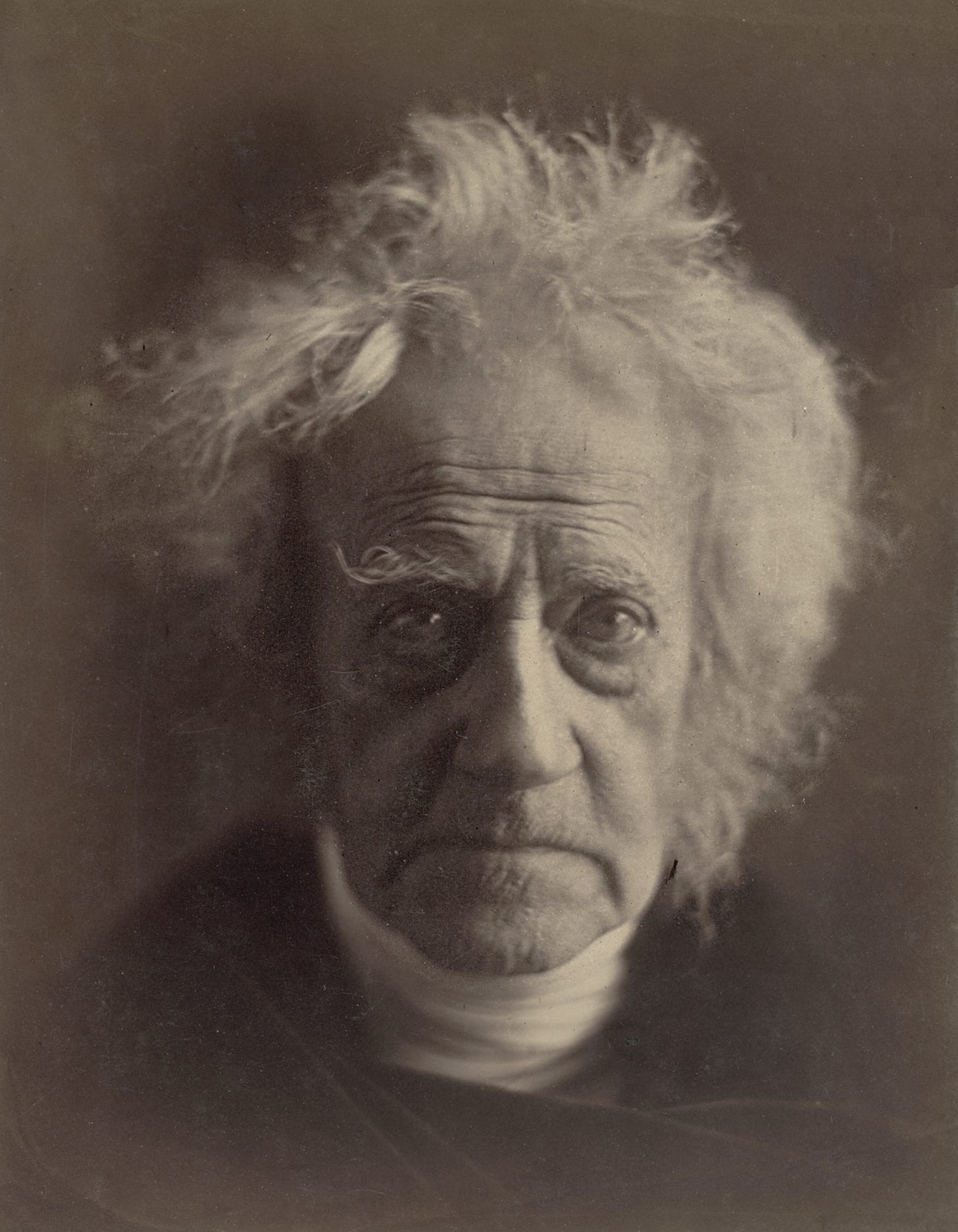

The photograph that fades

I came across something strange at an art exhibition this week. An artwork that used bacteria to create images. The label said it was inspired by something called Anthotype. I had never heard the word before.

So I did what curiosity always demands: I started digging.

An anthotype, I learned, is one of the earliest and most poetic forms of photography. An image made entirely from plants and sunlight.

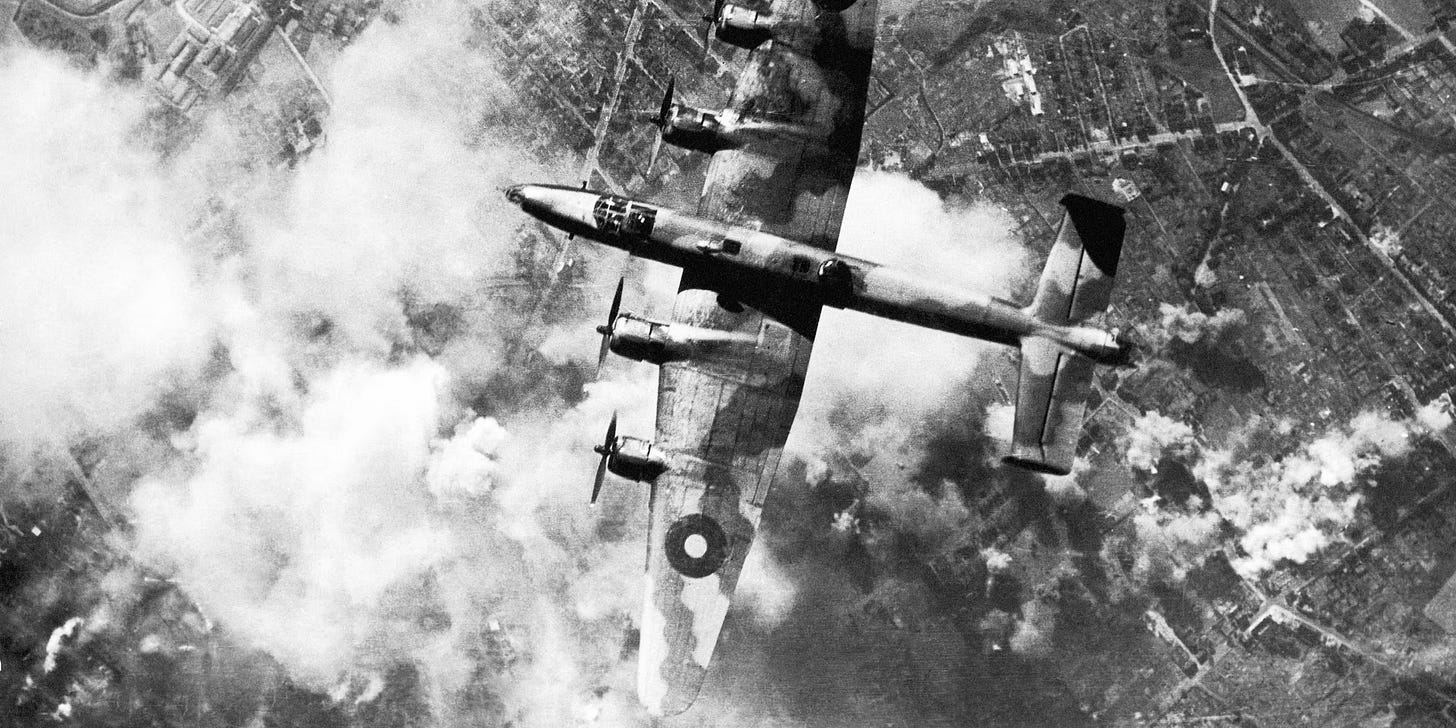

It was invented in 1842 by Sir John Herschel, the same English scientist who gave us the words photography, negative, and positive. Herschel was experimenting with the ways light could alter natural dyes extracted from flowers, berries, and leaves.

Here’s how it works:

- You crush petals or leaves to make a natural dye, beetroot, spinach, poppy, turmeric, whatever color you wish.

- You brush that pigment onto paper, let it dry in the dark.

- Then you place an object or a photographic transparency on top. A leaf, a feather, a face — and leave it under the sun.

- Over hours or days, light bleaches the exposed areas while the shaded parts remain rich with color.

- When you remove the object, what’s left is a delicate, plant-dyed image. A photograph made only of light and life.

No chemicals. No fixer. Just sunlight doing its slow, quiet work.

The catch, and for me the beauty, is that anthotypes fade. The same light that creates the image will, given enough time, erase it completely. So every anthotype begins its own disappearance the moment it’s born. That feels like a metaphor wrapped in chemistry. An image that embodies its own impermanence, a reminder that creation and decay are twins.

When the U.S. sent troops to Russia…

Last week I read a line that startled me: “The United States sent troops to Russia to fight the Bolsheviks.” What!? Seriously? So… I jumped onto the subject and this is what I found:

It happened after the war, in 1918. While Europe was celebrating peace, America quietly sent thousands of soldiers into the chaos of the Russian Revolution.

Russia had just dropped out of the war. The Tsar was gone, Lenin had seized power, and the new Bolshevik government had signed peace with Germany. The Allies panicked. Huge stockpiles of weapons and supplies were stranded in Russian ports, and they feared both Germany and the Communists might seize them. Another reason “was to rescue the 40,000 men of the Czechoslovak Legion, who were being held up by Bolshevik forces as they attempted to make their way along the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok, and it was hoped, eventually to the Western Front.”

So, about 5,000 Americans, mostly from Michigan, landed near the Arctic port of Archangel. They were told to protect supplies, maybe help anti-Bolshevik (“White”) forces. Instead, they found themselves fighting through –40°F snow in a civil war no one understood.

“We don’t know what we’re doing here,” one soldier wrote home.

By the spring of 1919, morale had collapsed. Families back home demanded their return. The troops withdrew soon after, their mission forgotten almost as soon as it ended.

About 235 American soldiers died during the U.S. intervention in Russia (1918–1920).

Here’s how that breaks down:

- Polar Bear Expedition (North Russia, around Archangel): roughly 244 deaths recorded in total, including those killed in combat, by disease, and from exposure. Around 110–120 were killed in action.

- Siberian Expedition (Vladivostok and eastern Russia): fewer combat deaths. Most estimates say 30–40 soldiers died, mostly from illness and accidents rather than battle.

Many of the dead from the Polar Bear Expedition were initially buried in Russian soil. Years later, in the 1920s, surviving veterans and families from Michigan raised funds to recover the bodies.