TWIL #44: From 40 Days to a Movie Painting

Quarantine: forty days that tried to hold back the world

I’m currently finishing Dan Brown’s Inferno, and somewhere between the Venetian canals and the apocalyptic puzzles, I stumbled on a word with history: quarantine.

Apparently the word comes from quaranta giorni, which means forty days. Why? Because that is the length of time arriving vessels were forced to wait offshore before anyone could set foot in the city. That rule was Venice’s attempt to stop something terrifying and invisible: the Black Death.

But the story doesn’t begin in Europe.

Long before it reached Venetian harbors, the plague was moving across China along the great arteries of trade: caravans, military routes, ports.

Historical estimates vary wildly, but most scholars agree that China may have lost between 25% and 40% of its population during the 14th-century outbreak: tens of millions of people. Entire towns vanished from the record. Officials wrote of “empty fields” and “streets without sound.”

From China, the plague likely traveled west with Mongol armies and merchants, threading through Central Asia and the Silk Road. It reached the ports of the Black Sea, where Genoese ships carried it, unwittingly, toward Europe.

By the time the plague arrived in Italy, Europe was already collapsing under it. In many regions, 30–60% of the population died. Venice (dense, interconnected, and dependent on trade) was no exception. Some estimates suggest around half the city’s population perished in the 1348 outbreak. In a city of perhaps 100,000 people, that means tens of thousands gone in a single year.

So when the next waves of plague approached, Venice acted.

First: thirty days of waiting offshore. The trentino.

Then: forty days. The quarantino, which gave us the word we use today.

The painting that stopped me: The Triumph of Death

While following the trail of plague history a single painting suddenly grabbed me.

Not a gentle discovery. More like being halted. I stumbled onto The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel and within seconds I felt myself pulled into a worldview far older and far harsher than ours. It was as if someone from the 1440s had reached across time and said: Look. This is how we saw life.

At the centre, Death on a skeletal horse fires arrows into a stunned crowd. A dead king lies in the corner, crown still on (and showing that death doesn't differentiate). The poor reach out to Death, begging for the release life never gave them. In the meantime, a skeleton gently helps an old man, as if guiding him out of pain. And then, on the opposite side, a shock of calm: two lovers, lost in music, unaware of the chaos around them.

Broken instruments, scattered jewels, indifferent dogs. Every detail whispers the medieval truth: life is fragile, and we only ever hold it briefly.

Barry Lyndon: a film shot like a painting

I watched the trailer for Barry Lyndon and immediately fell in love with the shots: they looked like paintings. I got so curious I started to dive into the backstory.

The painting-reference was Stanley Kubrick’s intention. He studied 18th-century painters like Gainsborough, Watteau, and Hogarth, trying to recreate their light, their stillness, their soft, lived-in textures.

To do it, he used something almost unbelievable: a NASA-designed ultra-fast lens capable of filming scenes lit only by candlelight. No hidden lamps. Just real flame, the way those painters saw the world.

The result is a film that feels less like a story being told and more like a gallery you drift through. Frame after frame glowing with historical quiet.

Stills from Kubrick's movie.

I have to admit, I’d never even heard of this movie before. Now it’s firmly on my list.

The Authoritarian Stack

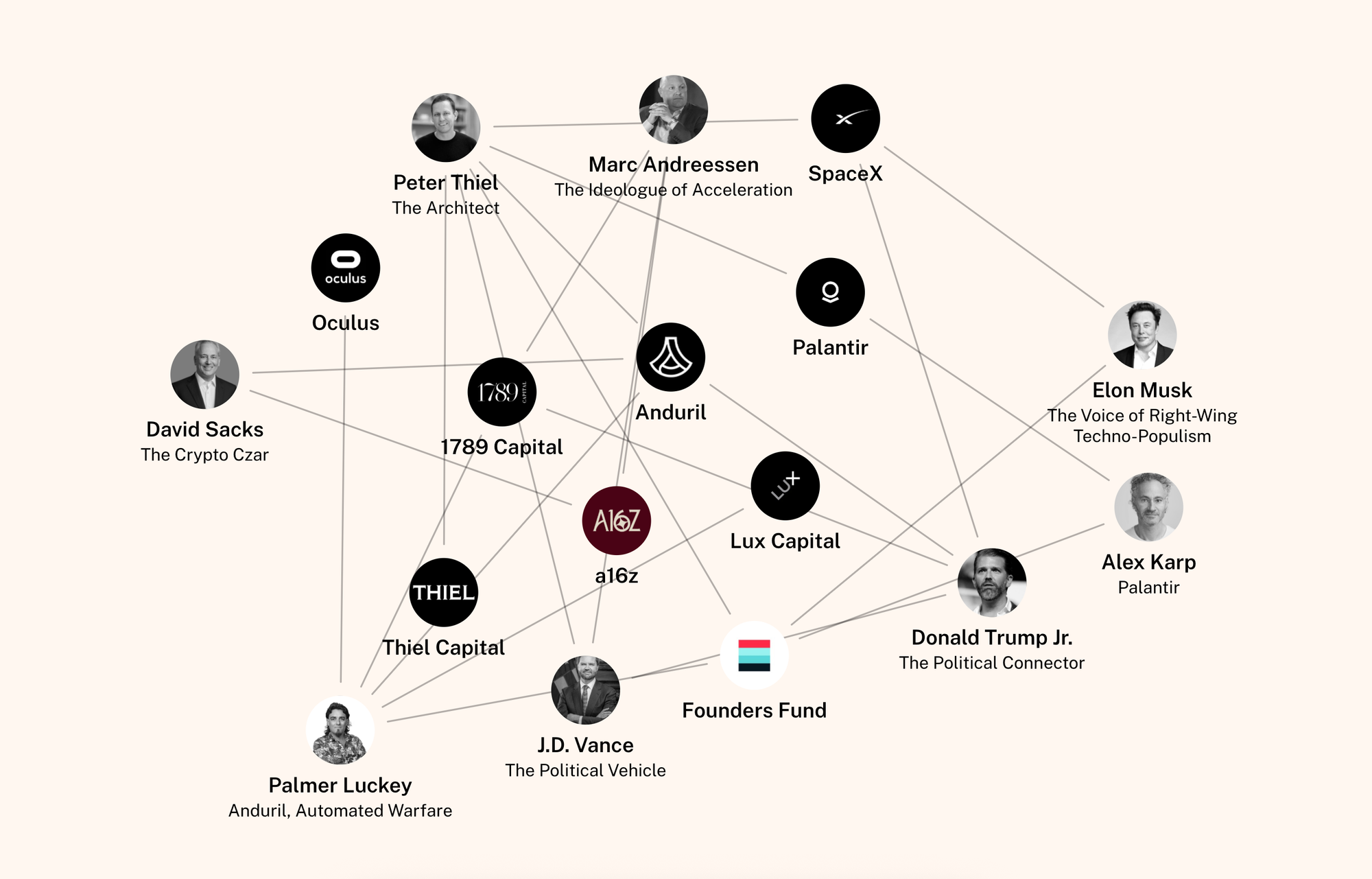

Wednesday I came across a project called The Authoritarian Stack via Stephen Anderson's newsletter, and it’s one of those ideas that clicks everything into place a little too clearly. It maps how big US tech, defense, and finance companies are quietly taking over roles once reserved for democratic governments: running cloud infrastructure, AI systems, border controls, security tools, even parts of national defense. All of it forms a kind of vertical corporate state, where public functions migrate into private platforms that no one votes for and few understand. It’s a fascinating, unsettling glimpse of how power is shifting into opaque networks, raising sharp questions about accountability, sovereignty, and what “governance” will mean in the years ahead.