TWIL #47: From Marriage Rituals to Marked Skin

Every Sunday, I write down a few things that caught my attention that week: details I tripped over, ideas that lingered, questions I needed to understand by putting them into words. This isn’t about being right or complete. It’s about noticing, wondering, and thinking on the page.

Thanks for reading. I hope something here sparks.

A moment that collapses time

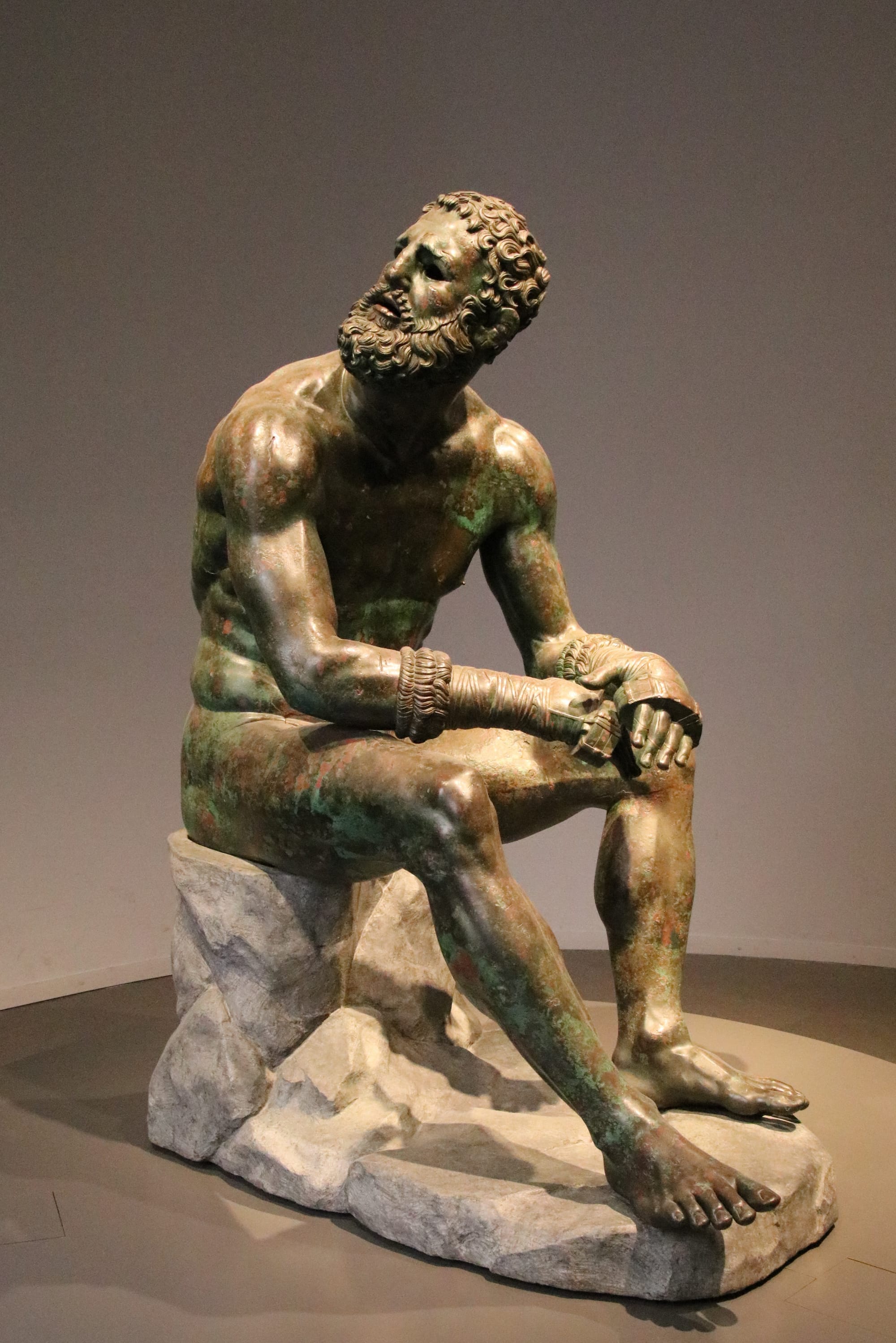

Sometimes you discover something not in a museum, but while wandering around the web. One image leading to another, curiosity doing its quiet work. I love ancient history, and this is how I stumbled across The Boxer at Rest.

At first glance, it doesn’t behave like an ancient statue is supposed to. There’s no triumph, no ideal pose, no perfect body inviting admiration from afar. Instead, there’s a man sitting down, bruised, bleeding, catching his breath.

And suddenly, the past feels close.

What pulls you in are the details.

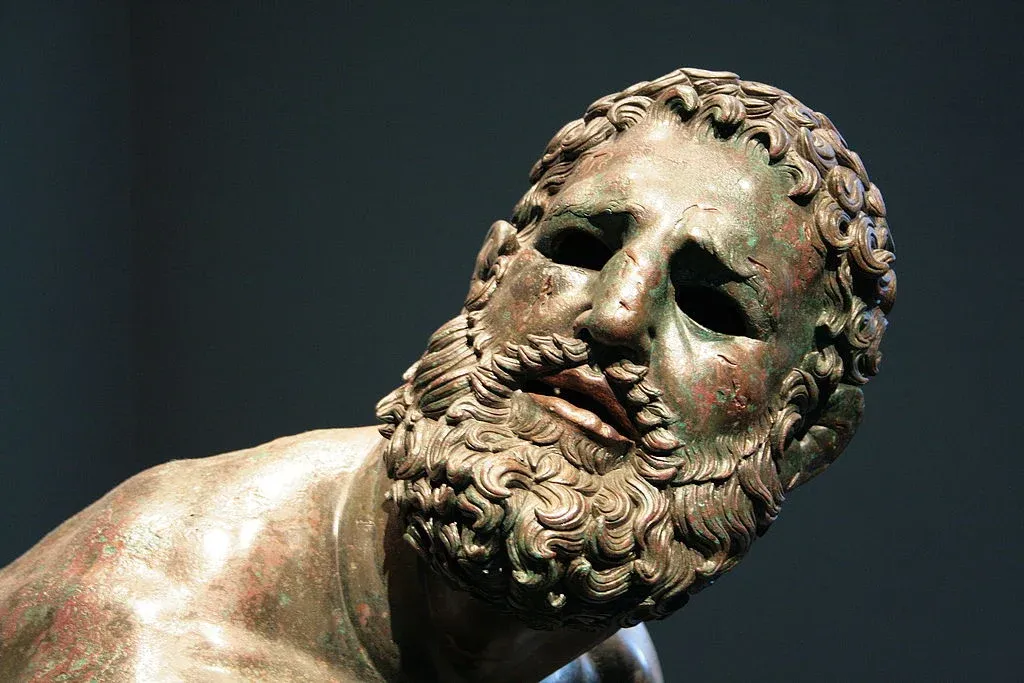

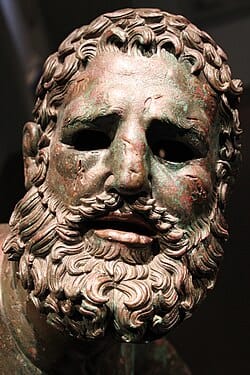

Look at his face.

The nose isn’t just broken. It’s been broken before. The asymmetry isn’t stylized; it’s accumulated damage. This isn’t one fight. It’s a life of them.

Look at his ears.

Swollen, thickened cauliflower ears. Not myth. Observation. With cuts and trails of blood (not painted, but inlaid copper so it catches the light differently).

Look at his hands.

Wrapped in himantes, leather straps weighted to make punches more brutal. They’re not raised in victory. They’re heavy, pulled down by gravity and fatigue.

Look at his pose. This is a glimpse caught for eternity.

And then there’s where he was found. Not in Greece, but in Rome, discovered in 1885 near what later became the Baths of Diocletian. That detail changes everything. The statue is Greek in spirit. likely Hellenistic, but Roman in survival.

The Romans loved Greek art. They collected it, copied it, displayed it, and protected it. While bronze statues were melted down elsewhere, Romans preserved them. And now they even think that "the Boxer was carefully buried to preserve its talismanic value, when the Baths were abandoned after the Goths cut the aqueducts that fed them." (source: Wikipedia). Thank you for that!

The marks marriages leave

I was watching Blue Eye Samurai this week. In it a Japanese woman prepared for marriage... Not with a dress, or flowers, or vows, but by blackening her teeth.

Not as a disguise.

Not as punishment.

As beauty. As status. As proof.

I paused the episode and went down a rabbit hole. Because once you notice it, you realise how many societies have marked adulthood, marriage, loyalty, and belonging directly onto the body. Often in ways that feel shocking now, but once made perfect sense.

Black teeth (Japan)

The ritual I saw is called ohaguro.

For centuries in Japan, married women dyed their teeth black using a mixture of iron filings and vinegar. White teeth were associated with youth, impermanence, and even animality. Black teeth, on the other hand, signaled maturity, stability, and commitment.

Bound feet (China)

In imperial China, marriage often began years before it happened: with foot binding. Girls’ feet were tightly bound in childhood so they would never grow properly. The ideal was the “golden lotus”: a foot small enough to fit in the palm of a hand. Walking became painful, slow, and dependent.

Bound feet signaled refinement, discipline, and family honor. They marked a girl as marriageable, delicate, and worthy of protection. Mobility was traded for status.

Marriage didn’t promise freedom. It promised containment.

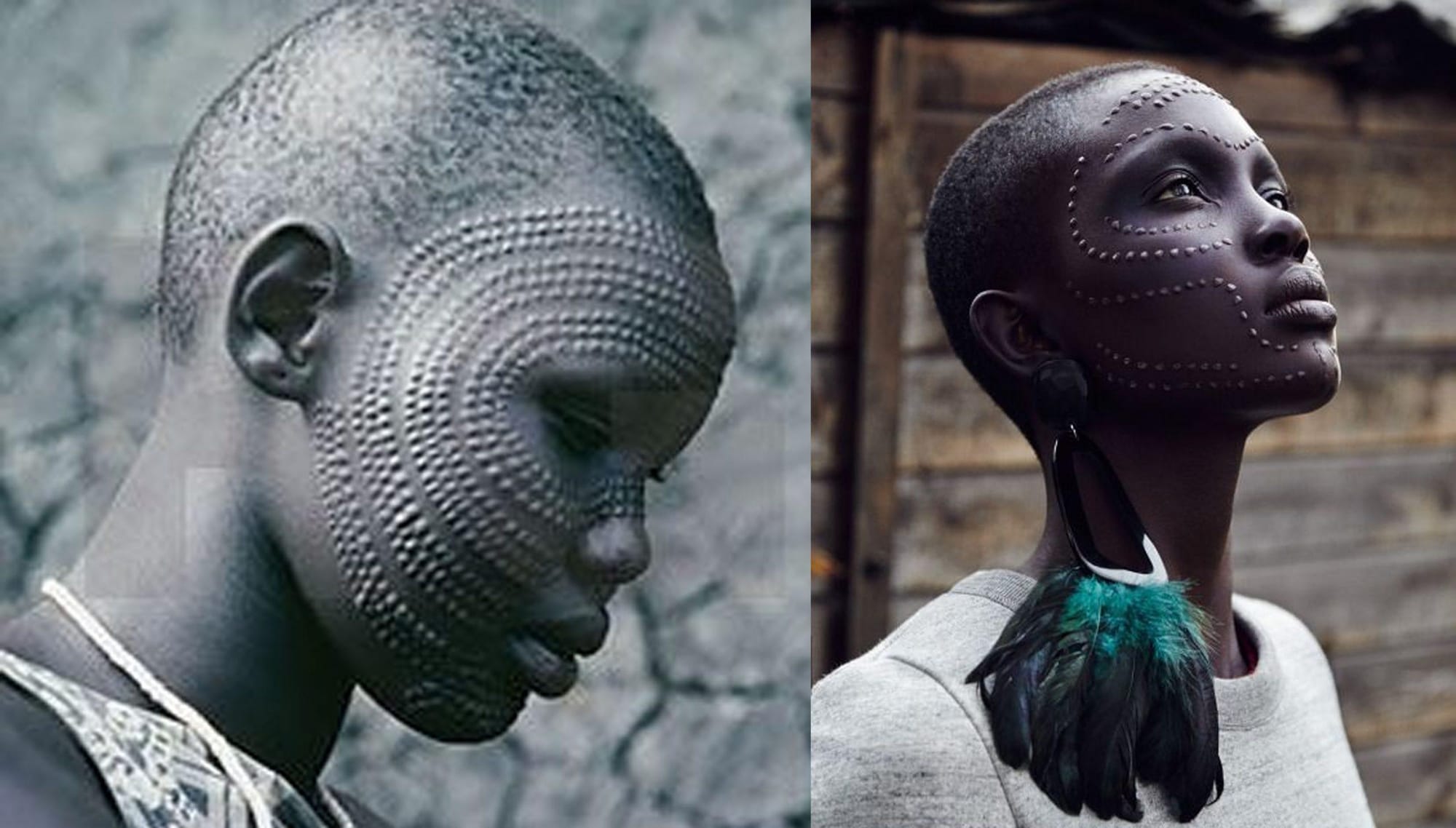

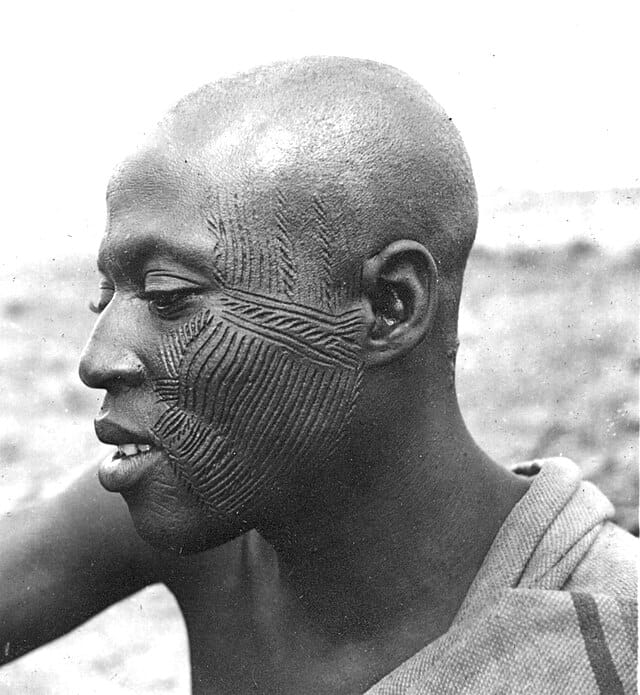

Scarification (Africa, Melanesia)

In many cultures across Africa and Melanesia, marriage and adulthood were (and are still) marked through scarification: deliberate, ritual cuts that healed into raised patterns. This ritual is for both men and women!

These scars were not hidden. They were beautiful. They showed endurance, belonging, lineage. They told others: this person has passed through something and emerged transformed. In some societies, scar patterns indicated whether someone was married, fertile, or ready to be.

Pain was not accidental. It was proof.

Hair as a social switch

Hair, across cultures, has often functioned as a marital signal.

- In ancient Rome, brides wore their hair parted with a spear: symbolizing transfer from father to husband.

- In many European traditions, married women covered their hair completely, while unmarried women wore it loose.

- In parts of India, the application of sindoor (red powder in the hair parting) still marks marriage today.

One small visual change. A completely different social identity.

Why more boys are born after a war

It sounds like folklore, but it keeps showing up in real data: after major wars, the ratio of newborn boys often increases slightly. Not enough to notice in a family, but enough to appear at the scale of entire populations. There’s no single explanation. Just several small forces pushing in the same direction.

They even have a name for it: returning soldier effect.

- Stress changes biology

Extreme stress alters hormone levels in men and women, which can subtly influence the chances of conceiving a male or female embryo. - Timing matters

After wars end, couples reunite and conception patterns shift. Those timing changes can slightly bias sex ratios. - Early pregnancy is fragile

Some female embryos are more likely to be lost very early under stressful conditions. This doesn’t create more boys — it changes who survives to birth. - Big events reveal small effects

Wars are so disruptive that tiny biological shifts become visible in population data.

The quiet takeaway: reproduction isn’t static. Even before societies rebuild, bodies are already responding to what the world has just been through.

That’s it for this week. 🫳🎤