TWIL #50: From Hydrogen to Urban Rebellion

Every Sunday, I write down a few things that caught my attention that week: details I tripped over, ideas that lingered, questions I needed to understand by putting them into words. This isn’t about being right or complete. It’s about noticing, wondering, and thinking on the page.

Thanks for reading. I hope something here sparks.

The universe started simple

Last week, I spent a few cold evenings photographing deep space with my Seestar S30. It is a slow hobby. Long exposures. Careful adjustments. Waiting for clouds to move, satellites to pass, the Earth to rotate just enough. Each new target pushes me to look up something unfamiliar, a nebula I have never heard of, a galaxy with an unmemorable name, a faint smudge that turns out to be unimaginably old.

Somewhere between stacking images and Googling what I was actually looking at, I ran into a simple and unsettling fact: at the beginning of the universe, there were only a few basic ingredients!

Mostly hydrogen.

Some helium.

A trace of lithium.

No oxygen to breathe.

No carbon for life.

No iron for planets, blood, or cameras.

Just raw material. Everything else came later, and slowly:

- Cooling down

After the Big Bang, the universe was too hot for structure. It took about 380,000 years to cool enough for the first atoms to form. Space became transparent. Light could finally travel. - Gravity gets to work

Over the next hundreds of millions of years, gravity slowly pulled hydrogen and helium into vast clouds. Nothing dramatic yet. Just gathering. - The first stars ignite

Around 100 to 200 million years after the beginning, the densest clouds collapsed. Pressure rose. Hydrogen ignited. The first stars were born, turning mass into light. - Making new elements

Inside stars, over millions to billions of years, simple elements fused into heavier ones. Helium became carbon. Carbon became oxygen. Step by step, the periodic table began to grow. - Stars die and scatter

When large stars ran out of fuel, they collapsed and exploded. These deaths, happening after millions to billions of years, flung newly made elements into space. - Recycling begins

New stars formed from this enriched debris. Around them, disks of dust and gas condensed into planets. This process took tens to hundreds of millions of years. - Chemistry gets complicated

On at least one planet, over billions of years, chemistry crossed a threshold. Molecules learned to copy themselves. Life appeared. - Looking back

Much later, after roughly 13.8 billion years, parts of the universe learned how to observe the rest of it.

Not through speed.

Not through planning.

But through time, pressure, collapse, and reuse.

The striking thing for me is not how much is out there. It is how little it started with, and how much patience it took to get here.

It makes me wonder: are we always giving our own ideas, places, and lives the amount of time they deserve to become something magical?

Things I bumped into online

Small discoveries from wandering the web, without a plan.

→ SmartHistory

A website filled with art, architecture, history from every continent, prehistoric to today. And it is interpreted by leading scholars!

https://smarthistory.org/

→ OutHistory

OutHistory is a public history website that aims to generate, present, and promote high-quality evidence-based LGBTQ historical research for LGBTQ and general audiences.

https://outhistory.org/

The Dérive: A small act of urban rebellion

In the 1950s The Situationists were frustrated.

They looked at modern cities and saw lives being quietly programmed. People moved along the same routes, followed the same routines, consumed the same experiences. Streets, signs, and schedules decided behaviour long before any conscious choice was made.

For the Situationist International, this was not accidental. It was how modern society worked. Everyday life had become predictable, efficient, and dull. Experience was being replaced by repetition.

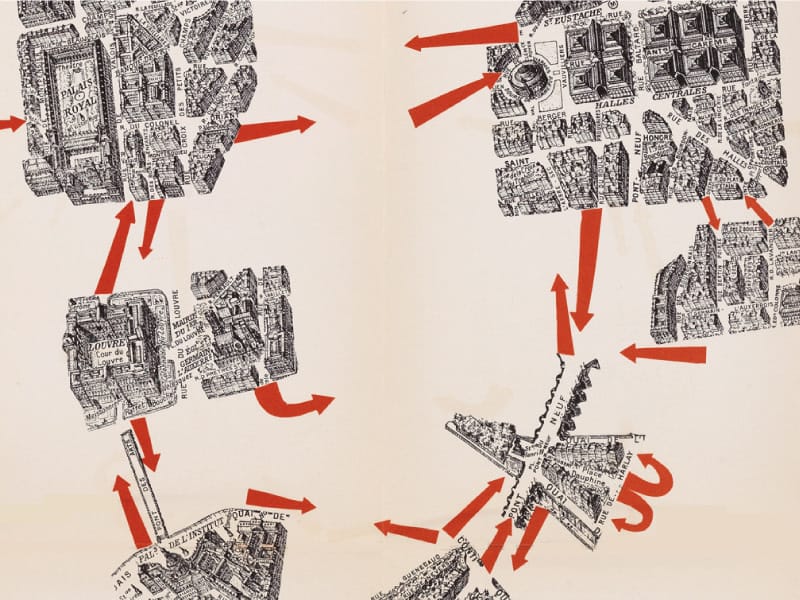

The dérive was their response.

The word dérive means “drift”. It was a way to break, temporarily, from the script of the city. A dérive means walking without a destination. No route. No plan. You let the city pull you. You turn because something catches your eye. You stop because a place feels different. You leave when an area drains your attention.

This is not about getting lost.

It is about noticing.

As you drift, patterns appear. Some streets make you rush. Others slow you down. Some places invite lingering. Others quietly push you away. The Situationists believed these reactions were shaped by the city itself, not personal mood.

Today, the dérive feels newly relevant. Navigation apps optimise every move. Efficiency replaces curiosity. We arrive faster, but notice less.

The dérive offers a simple invitation:

Leave your phone in your pocket.

Take an hour with no destination.

Let the city decide, for once, where you go.

The Wall in Wall Street

If you walk down Wall Street today, the name feels abstract. Banks, offices, glass, flags. No wall in sight.

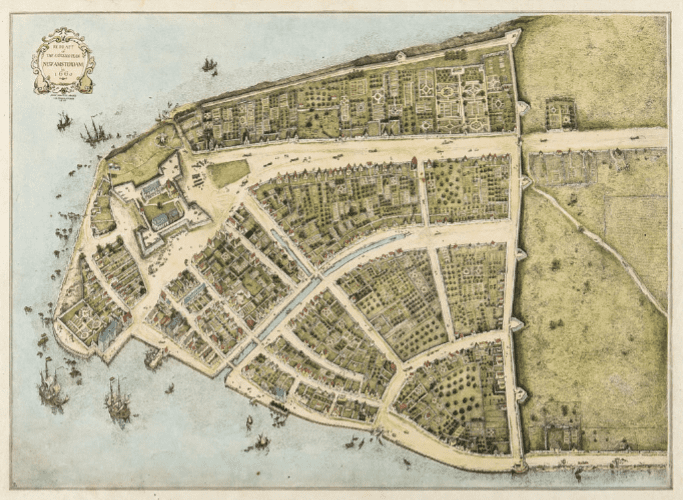

But the name is literal: In the 17th century, New Amsterdam, the Dutch settlement that later became New York, built a wooden defensive wall at the northern edge of the town. It was meant to keep out enemies, control movement, and mark where the city ended.

The street that ran alongside it became Wall Street.

When the wall disappeared, the name stayed.