TWIL #51: From Futuristic Games to Old Borders

Every Sunday, I write down a few things that caught my attention that week: details I tripped over, ideas that lingered, questions I needed to understand by putting them into words. This isn’t about being right or complete. It’s about noticing, wondering, and thinking on the page.

Thanks for reading. I hope something here sparks.

When Chewbacca’s chess became real

Remember that scene aboard the Millennium Falcon where Chewbacca plays holographic chess (and gets frustrated and angry when he loses the game). In the game creatures appear in mid-air. They occupy space. They feel present. No one explains the technology. It simply is there. And we all wished we had it.

Today, I discovered volumetric holograms. And technology from a galaxy far, far away.. just became reality:

No screens. No headsets. Just a shared space in the room.

Volumetric holograms are not flat projections. They are light arranged in space. You can walk around them. Others see the same object from their own angle. The experience is collective by default. Isn't that great?

As you can see the resolution (and probably the refresh rate) is still low... but give it time and this will evolve.

I can already see the endless possibilities:

- Museums where artifacts can be played with: rotating, layered with context, without glass cases

- Gaming that feels social again, something you gather around rather than disappear into

- Classrooms where complex ideas float, move, and can be explored together

Reflections

Last week I saw this image.

At first, I thought it was created with AI. Something recent. Something designed to provoke reflection through contrast and symbolism.

Then I found out it was painted in the 1980s.

Reflections is the work of Lee Teter, a Vietnam War veteran. The context matters. The painting emerged at a time when the Vietnam War was still unresolved in the collective psyche. Veterans were returning to a society that struggled to understand what they carried back with them.

The image itself is simple. A person standing in front of a the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, with on it the names of fallen comrades... fallen friends.

That restraint is what gives the work its power.

Just look at it. Let the image sink in.

Some things don’t ask to be analyzed. They ask to be felt.

Where does Europe actually end?

My kid was doing geography homework this week. He looked up and said, surprised: “Kazakhstan is in Europe?”

I found myself answering almost automatically.

“Yes, of course.” And then I paused.

Because as I said it, another question surfaced.

How do we even know that?

Why does this line exist at all?

So... I started to explore.

The line we call Europe

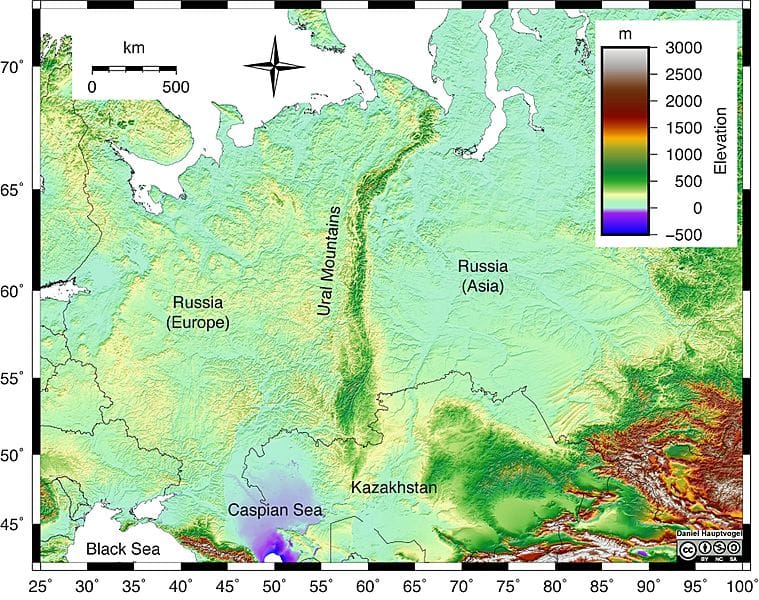

Most atlases draw Europe’s eastern edge along the Ural river in Russia, the Caucasus Mountains and the Bosporus (splitting Istanbul in half).

Follow that path from the Ural Mountains to the Caspian Sea and a small part of Kazakhstan ends up in Europe.

It looks definitive. Almost natural. But it isn’t.

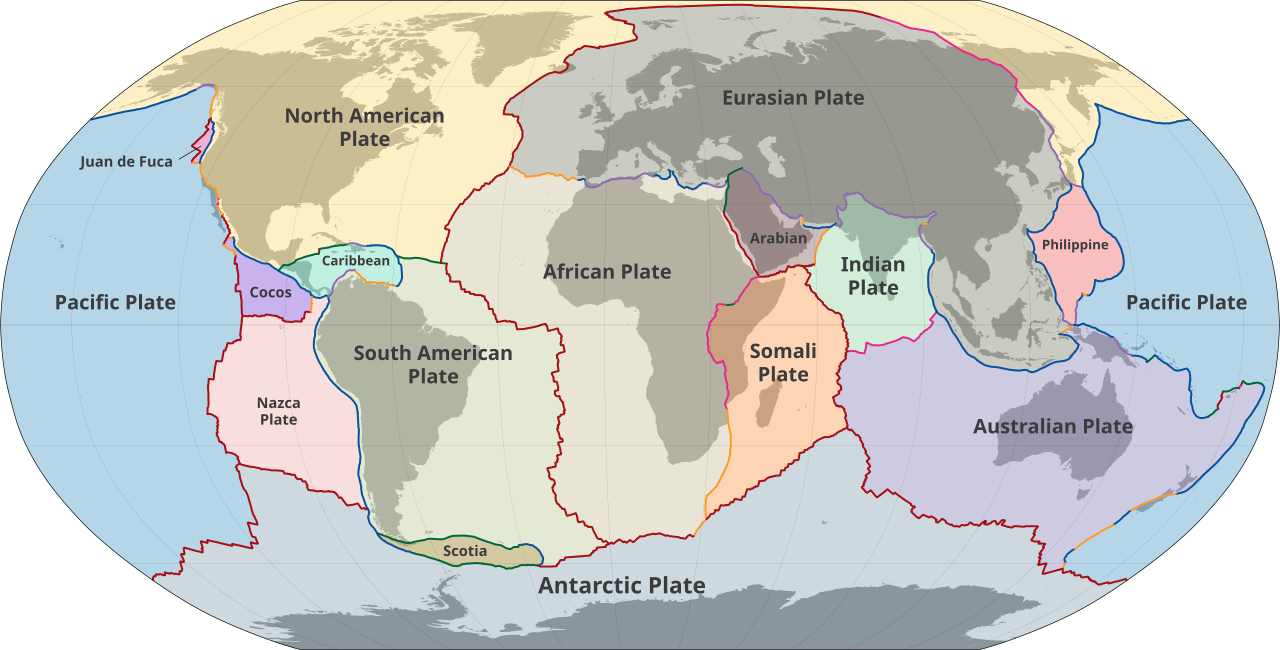

Europe isn’t a tectonic plate.

The Eurasian Plate is.

The division between Europe and Asia apparently goes back to the ancient Greeks. For them, the world was not divided by plates or faults, but by familiarity.

- Europe meant us

- Asia meant them

- The boundary marked culture, not land

At that time, the Greeks had no concept of Russia, no knowledge of Central Asia. Yet the idea survived. As maps expanded eastward (and northward), the distinction came along for the ride.

Why did Russia end up in Europe?

At first glance, the answer seems obvious: the Ural Mountains. But that explanation comes surprisingly late in the story.

Russia did not become European because a mountain range said so. It became European because of where it looked, who it traded with, and which stories it told about itself.

- Moscow and later St. Petersburg faced west

- Christianity, administration, and education came from Europe

- Russia’s population and political gravity sat west of the Urals

The map simply had to catch up. So the Urals were chosen:

- They run north to south

- They look convincing

- They create a clean edge on paper

Only then did geography step in to justify what culture had already decided: Kazachstan being a part of Europe.