TWIL #54: From Acid Oaks to Ancient Trails

Every Sunday, I write down a few things that caught my attention that week: details I tripped over, ideas that lingered, questions I needed to understand by putting them into words. This isn’t about being right or complete. It’s about noticing, wondering, and thinking on the page.

Thanks for reading. I hope something here sparks.

A walk, a dog, and an unexpected oak

I was walking the dog through the forest earlier this week when I started chatting with a photographer I met on the path. We were talking about birds... or more accurately, about how quiet the forest feels lately. Fewer songs. Less sudden fluttering in the trees. A stillness that feels newer than it should.

Almost casually, he randomly said:

“Dutch nature is being harmed more by acid effects around American oak than by farming.”

At first I brushed it off. It sounded too simple for something so complex. But later I looked into it, and it turns out there’s something to it.

Those American oaks were planted deliberately more than a century ago because they grew fast, straight, and survived poor soil. Forest managers at the time were trying to rebuild woods quickly. Not protect biodiversity.

European oak (left) vs American oak (right)

What I didn't know:

- American oak leaves break down much more slowly than native oak leaves

- They contain more tannins than other leaves, which slowly acidify the forest soil

- Forest floors beneath them often have far fewer wildflowers and small plants

- And where plants disappear, insects follow... and birds soon after

- Plus most European insects can’t feed on the leaves, because of the different chemistry

Nothing collapses overnight.

It’s more like the volume gets turned down year after year.

What struck me most was this: the tree never changed. Our idea of what a forest should be did. We moved from seeing forests as timber factories to living ecosystems. And suddenly old “solutions” look complicated.

It made me realize how quietly landscapes carry the memory of human decisions long after the reasons for them are forgotten.

The Icknield Way: Britain’s prehistoric road trip

I love landscape. It always tells a story.

So I came across the Icknield Way and discovered one of Britain’s oldest and most fascinating journeys written straight into the land itself. This is not just a walking route. It is one of the oldest roads in Europe, shaped by footsteps over thousands of years.

Imagine... a route that is over 5,000 years old!

Long before maps and milestones, people followed this natural chalk pathway to trade, travel, and connect communities. Farmers, warriors, and merchants all passed this way, leaving behind a trail of history that still feels alive today.

- Neolithic farmers

The first settlers, moving livestock and trading flint tools - Bronze and Iron Age tribes

Traders and warriors linking hill forts and communities - Roman-era travelers

Locals continuing to use the ancient route alongside Roman roads - Anglo-Saxon villagers

Connecting early English settlements and markets - Medieval pilgrims and drovers

Walking to holy sites and driving livestock to distant towns - Modern walkers and people on gravel bikes

Exploring one of Europe’s oldest living paths

Thousands of years. One landscape. Endless stories carried along the same trail.

The Icknield Way stretches about 130 kilometer, running from Norfolk down to Wiltshire. Much of it hugs the edge of the chalk hills, especially the sweeping scenery of the Chiltern Hills. Walking it probably feels like drifting through a painting. Open skies, soft white paths, rolling fields, hedgerows buzzing with life, and villages that seem gently preserved by time.

What makes the Icknield Way unforgettable is not just its age, but its calm. Much of it remains untouched by modern life. And along the way you can visit some Britain’s most ancient and atmospheric places:

- Avebury, a vast stone circle older than Stonehenge

- Ivinghoe Beacon, an Iron Age hill fort with sweeping views

- Wayland’s Smithy, a 5,000 year old burial chamber hidden in woodland

- Uffington White Horse, a giant Bronze Age figure carved into the hillside

Avebury and the Uffington White Horse

This one just got added to my bucket list!

All the gold we see on Earth is basically space debris

This isn’t something I learned this week... but it popped back into my mind when I saw yet another gold rush headline.

Almost all the gold on Earth is alien.

When the planet was young and molten, heavy elements like gold sank straight into the core. If that had been the end of the story, we’d have almost none of it in the crust.

But then Earth got bombarded by asteroids, leftovers from the early solar system, and they brought gold with them. Atom by atom. Scattered into rock and riverbeds.

Every ring, coin, and bar is essentially stardust that arrived very late and very violently.

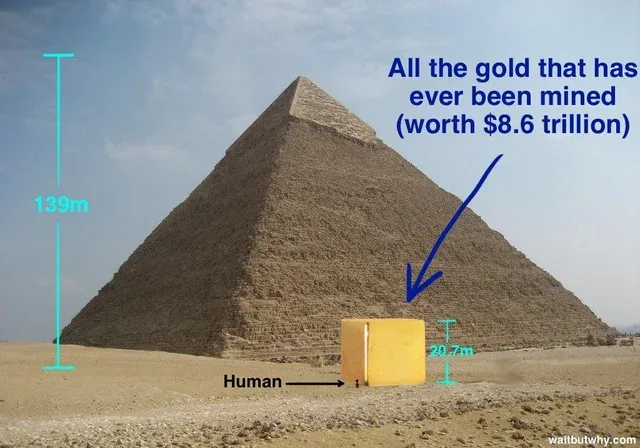

Even better: if you melted down all the gold humans have ever mined (every crown, vault bar, statue, and tooth filling) it would form a cube about 22 meters tall. About the height of a small apartment building. That’s it.

For something that has driven empires and obsessions, it’s shockingly small.

Gold feels eternal and abundant, but really it’s just rare cosmic leftovers that happened to stick around.